As frequent readers of this blog are well aware, my approach to understanding business cycles is most closely associated with the Post-Keynesian sub-disciplines of Monetary Realism (MR) and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). The order of appearance is intentional since I find myself more frequently in disagreement with MMT when its proponents stray too far from their monetary operations expertise into the realm of policy recommendations. Though I support the government’s ability to offset private sector deleveraging with budget deficits, I find it troubling that more specifics on the distribution of funds and current tax laws are often omitted from the discussion.

Although these disagreements are meaningful, they do not discount the shared goal of promoting multi-sectoral analysis of business cycles. Thornton (Tip) Parker, at New Economic Perspectives, puts forth two ideas to further this goal. His first idea revolves around the issue of wealth and income concentration that I noted above:

The wealthy use much of their money just to make more money by gambling through hedge funds, leveraged buy-out funds, and other financial schemes. They take some out of the economy by spending in other countries and hiding from taxes with off-shore accounts. They are not using much to make productive investments to create more jobs that would provide good pay and benefits in this country. Too much of what high earners receive leaks out of the Main Street economy to Wall Street, and often to other countries.

I do not think that MMT and MS consider the leak adequately. They explain why the government must create more new dollars to offset private sector and foreign surpluses. But they do not explain how to prevent many of those dollars from flowing up and increasing the wealth concentration. I suspect that more dollars flow out of the Main Street economy through the leak than as payments for net imports. Just the need of many middle and lower income families to borrow ensures that some of their income will flow up in the form of interest and finance charges. (Margrit Kennedy has recently estimated that thirty-five to forty percent of all purchases go to interest.)

The effect of concentration might be analyzed by dividing households into two subgroups, one for the wealthy (say top 10%) and one the rest. Showing each subgroup’s surplus or deficit in relation to the rest of the private sector and the foreign and government sectors would show how much of a problem inequality really is.

I know of no easy way to do that, but conceptually, it would debunk the idea that income inequality is an envy, special pleading, or made-up class warfare issue. It would also show that taxes can do more than just prevent inflation, they can be used to limit the leak of money out of the productive parts of the economy.

Though this research project faces significant challenges, the potential results could vastly improve current policy discussions both among Post-Keynesians and in the broader political arena.

Related posts:

Debt Inequality Remains Major Headwind To Growth

Bubbles and Busts: IMF - Leveraging Inequality

Bubbles and Busts: Forgotten Lessons from Japan's Lost Decades

Hayekian Limits of Knowledge in a Post-Keynesian World

Since the ACA (“Obamacare”) was enacted, a significant portion of my friends and family have been pleased with the extra benefits accrued at seemingly no cost. Although the cost may be difficult to perceive today, it is certainly present and will become increasingly relevant in the coming years. Setting that debate aside for the moment, readers should be aware of a couple significant loopholes in the ACA pointed out by the typically liberal Yves Smith of naked capitalism:

It will cover people with preexisting conditions. Um, maybe, until you need costly care. The ACA preserved a loophole you can drive a truck through: But the bill has a giant loophole: insurers can continue to cancel policies in the case of “fraud or intentional misrepresentation” as they do now. And the bar for fraud, per established case law, is remarkably low. Forgetting to tell your insurer about a past ailment, no matter how minor, qualifies. Say you forget to tell your new insurer that you had acne or a concussion in your teen years. That will more than do.

…

Your health care will be (mainly) covered. Hahaha. I know high functioning people (as in couples where both spouses had advanced degrees, and one was on the board of a major medical devices company) who’ve been stuck with huge hospital bills. They’d thought everything was covered, and somehow items that were in the tens of thousands (in one case, totaling $75,000) wasn’t. And then there’s the “out of network” problem, highlighted this weekend by a New York Times story of parents who had a baby that had trouble sleeping and the pediatricians they saw were at a loss. The doctor who specialized in that sort of problem didn’t accept insurance. While he was able to help the baby, the parents had to foot all of the $650 bill.

Prior to reading Smith’s post, I had expected the second loophole but was surprised by the first. Individuals with pre-existing conditions unfortunately cannot alter potential past misrepresentations, but should proceed with greater care in divulging their medical histories.

Smith goes on to argue against a third area of praise for the ACA, which may provide an opportunity for investors:

Health insurer profit margins are capped. That is technically accurate but substantively misleading. The health insurer have been engaged in price gouging over the last two decades. Health insurers as of the early 1990s spent 95% of health care premiums on medical expenditures. They now spend less than 85%. The ACA requires them to spend 80% on health care costs. So the bill institutionalizes an egregiously fat profit margin.

The major health insurers, Wellpoint (WLP), UnitedHealth Group (UNH) and Cigna (CI), continue to trade off their pre-ACA highs despite rising profitability. Many analysts and investors appear convinced that the ACA will hurt future profits, when in reality it may ensure strong profits going forward.

Related posts:

The Relative Strength of US Health Care

Auerback & Wray: America Needs Healthcare, Not Health Insurance

(Disclosure: I am currently long WLP.)

Over at Mike Norman Economics, Mike Norman poses the question, “Would rates be higher if the Fed hadn’t done QE?” Before I get to his answer, let me acknowledge that this question has crossed my mind a number of times over the past couple years. The answer I have settled on is that rates would be lower and let me explain why. There is a broad misconception about what QE (effectively open-market-operations) really means on an operational basis. I’ve tried to explain this many times but Mike offers a succinct explanation:

In so doing the Fed changes the composition and duration of the financial assets held by the public. It's not stimulus, it doesn't enable gov't spending and it's not money printing. These are asset swaps, that's it, pure and simple.

QE reduces the default risk and shortens the duration of financial assets held by the private sector (i.e. public). Assuming risk preferences do not change significantly during this process, the private sector will likely counter QE by shifting other assets to higher risk and longer duration securities. The result is a smaller tradable supply of Treasuries and decreasing demand. Since a significant portion of QE has and continues to involve purchasing Agency-MBS instead of Treasuries, my intuition is that the demand effect trumps the change in supply. Without QE, the demand and supply of Treasuries would therefore be higher, with the larger demand effect pushing up prices and lowering rates.

A significant portion of Mike’s argument is worth highlighting (my emphasis):

when the government spends it adds to the level of bank reserves in the system and this accumulation of reserves causes the Fed to engage in monetary operations on a fairly regular basis (like, daily) to maintain reserves at a level that is consistent with whatever target interest rate they have decided upon. If the Fed were to allow reserves to build and build and build as a normal consequence of ongoing gov't spending, then the overnight lending rate (Fed Funds) would quickly fall to zero and all other rates out along the term structure would follow suit.

So the fact of the matter is the Fed has to work quite hard to KEEP RATES FROM FALLING TO ZERO ON THEIR OWN if the banking system were just left alone without its intervention. Those who say the Fed is keeping rates "artificially low" have got it backward. On the contrary, high rates or rising rates for a currency issuing nation are artificial.

The first statement in bold is often overlooked or misunderstood but critical to understanding monetary operations and its impacts. Clarifying Mike’s point, since taxation actually decreases the level of reserves, government spending in excess of revenues causes reserves to build. Scott Fullwiler addresses this issue in a fantastic paper on Interest Rates and Fiscal Sustainability:

When a deficit is incurred, in order for the Fed’s interest rate target to be achieved either the Fed or the Treasury must sell bonds in order to drain the net addition to reserve balances a deficit would create. If no bonds were sold, the deficit would generate a system-wide undesired excess reserve balance position for banks. (p. 17)

Based on this analysis, the conclusion is pretty clear:

The notion that rates would have been higher if the Fed had not done QE is false.

Related posts:

Fullwiler - "The main shortcoming of the money multiplier paradigm"

Bubbles and Busts: Why QE2 Failed, Part 1

Modern Money Regimes Redefine Fiscal Sustainability

Fed's Treasury Purchases Now About Asset Prices, Not Interest Rates

"Interest-On-Reserves Regime" Will Rule Monetary Policy For The Foreseeable Future

Noah Smith discusses Bob Lucas on macro:

I find Bob Lucas more intriguing than any other economist of the last few decades. I'm always interested to read what he has to say, for example in this recent interview (hat tip to Steve Williamson).

Lucas is also near the top of my list and I should add that I generally enjoy reading whatever Noah has to say (although I don’t always agree). Here is the portion I found most intriguing:

Lucas on the causes of business cycles:

"I was [initially] convinced by Friedman and Schwartz that the 1929-33 down turn was induced by monetary factors...I concluded that a good starting point for theory would be the working hypothesis that all depressions are mainly monetary in origin. Ed Prescott was skeptical about this strategy from the beginning...

I now believe that the evidence on post-war recessions (up to but not including the one we are now in) overwhelmingly supports the dominant importance of real shocks. But I remain convinced of the importance of financial shocks in the 1930s and the years after 2008. Of course, this means I have to renounce the view that business cycles are all alike!"

In 1980, Lucas had written:

"If the Depression continues, in some respects, to defy explanation by existing economic analysis (as I believe it does), perhaps it is gradually succumbing under the Law of Large Numbers."

But with the post-2008 recession looking so similar to the Depression, it seems to have become clear to Lucas that the Law of Large Numbers will no longer do the trick. There must in fact be two types of recessions, with one (more frequent, less severe) type caused by "real shocks", and the other (rarer, more severe) type caused by "financial shocks".

That Lucas has now twice changed his ideas about the underlying causes of the business cycle - the most important question in all of business cycle theory - is in my opinion a reason to admire him. When the facts change, Lucas changes his mind, as any scientist should.

Lucas is clearly a brilliant thinker, yet despite his best efforts, he was unable to generate a theory of business cycles that could sustain experiences during his own lifetime. While his willingness to change his mind is commendable, the degree to which this trait garners admiration implies the sad truth that very few live up to this standard.

Moving beyond the sad state of science (economics), I find it partially validating that Lucas now admits to the possibility/reality of “financial shocks”. The most recent “financial shock” is a primary reason behind my decision to pursue a degree in economics and create this blog. My future research will most likely focus on the monetary origin of such shocks, although presumably in a different light than Lucas (and Noah) would envision.

As I endeavor to find a new theory that helps explain the underlying causes of business cycles, Lucas’ story offers a reminder not to adhere too strongly to any theory, model or research project and to let the facts speak for themselves.

While I generally support a smaller federal government, I would be remiss in not mentioning that my childhood years in Montgomery County (a suburb of DC) and current Washington DC residency are greatly enriched by the government’s increasing legislative power. In fact, the district was among a few select areas where employment and housing prices were barely affected by the recent recession and financial crisis. Now a couple years into the recovery, DC is still humming along. Here’s Glenn Reynolds (h/t Scott Sumner):

We don’t live in The Hunger Games yet, but I’m not the first to notice that Washington, D.C., is doing a lot better than the rest of the country. Even in upscale parts of L.A. or New York, you seeboarded up storefronts and other signs that the economy isn’t what it used to be. But not so much in the Washington area, where housing prices are going up, fancy restaurants advertise $92 Wagyu steaks, and the Tyson’s Corner mall outshines — as I can attest from firsthand experience — even Beverly Hills’ famed Rodeo Drive.

Meanwhile, elsewhere, the contrast is even starker. As Adam Davidson recently wrote in The New York Times, riding the Amtrak between New York and D.C. exposes stark contrasts between the “haves” of the capital and the have-nots outside the Beltway. And he correctly assigns this to the importance of power.

Washington is rich not because it makes valuable things, but because it is powerful. With virtually everything subject to regulation, it pays to spend money influencing the regulators. As P.J. O’Rourke famously observed: “When buying and selling are controlled by legislation, the first things to be bought and sold are legislators.” But it’s not just bags-of-cash style corruption. Most of the D.C. boom is from lobbyists and PR people, and others who are retained to influence what the government does. It’s a cold calculation: You’re likely to get a much better return from an investment of $1 million on lobbying than on a similar investment in, say, a new factory or better worker training.

Related posts:

Over the past few weeks and months, the chorus of economic and financial analysts singing praises about the housing rebound has been growing. Some believe housing will come roaring back, significantly boosting GDP, as in those good old days of the early 2000’s. Others remain more subdued about the prospects, expecting stability with potentially moderate growth. It’s certainly hard to argue with those positions given recent data, as shown below:

Recently prices are clearly trending higher, but a quick glance at late 2009-early 2010 shows a similar pattern. Will house prices continue the recovery, flatten out, or take a turn towards new lows?

Supporting the bullish case:

- Mortgage rates are at all time lows

- The Fed is actively buying Agency-MBS to push rates lower

- Real house prices and price-to-rent are back to late 1999 levels (Calculated Risk)

- New and existing home sales are rebounding

- Government support remains strong

There are certainly many other bullet points one could add, but I want to focus on the last point, which might strike some as odd.

Do you know what percent of the current mortgage market is either owned or guaranteed by the GSEs (Fannie Mae And Freddie Mac) and the FHA (Federal Housing Administration)?

If not, would you guess...

A) 50%

B) 70%

C) 90%

D) 95%

The correct answer is C - 90%.

So why does this support the bullish case? Well, the various government agencies have primarily gained market share by offering mortgages and guarantees at prices well below any private sector participant. Seemingly unphased by fallout from the recent housing crisis, the FHA is once again doling out mortgages to subprime borrowers with down payments as low as 3.5%. Similar to the previous housing boom, this cheap credit should increase purchasing power and at least place a floor under housing prices, if not drive them higher.

Turning to the bearish position, one must recall that the government’s previous efforts to accurately price mortgage loans and guarantees ended with massive losses for the taxpayers through the GSEs. While risks of further GSE losses remain high, the FHA is quickly racking up losses on bad loans and will need capital injections (a bailout) from the Treasury. In light of these outcomes, there may be some pressure to shift part of the mortgage market back to the private sector.

Walter Kurtz at Sober Look explains that In order for the private sector to step into the mortgage market, g-fees need to rise:

The only way to shift at least some of the mortgage business to the private sector (currently the GSEs and the FHA own or guarantee over 90% of the US mortgage market) is to price the risk closer to where it would be priced in the private sector. Otherwise the private sector will never enter this market - other than to sell the mortgages banks originate to the government and keep the origination fees (which is what banks do now).

The taxpayer also needs to recoup the Fannie and Freddie rescue expenses. That means the GSEs will need to raise their g-fees, which according to JPMorgan is exactly what they plan to do (chart below).

These projected increases in g-fees will, ceteris paribus, push mortgage rates higher at a time when the Fed is trying to force rates in the opposite direction. Although the magnitude of 20-30 basis points is seemingly small, it is practically equivalent to the change from the Fed’s QE programs that are believed by many to have extraordinarily powerful effects. While I remain skeptical of the potential impact from a change of this magnitude, the trend higher in g-fees presents a potential headwind for future house prices.

Whether or not the rise portrayed above occurs remains open for debate and is being fought by numerous politicians. The reality is that the direction of US housing prices, at least in the short-run, lies primarily with the actions of the US government. Continuing the current practice of lending at below market prices across the credit spectrum may succeed at inducing a credit-infused rebound. In all likelihood the outcome will be no different than recent experiences around the globe, as the debt burden will overwhelm income and savings, leading to housing price declines and massive taxpayer losses.

1) What Drives Trade Flows? Mostly Demand, Not Prices by JW Mason @ The Slack Wire

The heart of the paper is an exercise in historical accounting, decomposing changes in trade ratios into m*/mand D*/D. We can think of these as counterfactual exercises: How would trade look if growth rates were all equal, and each county's distribution of spending across countries evolved as it did historically; and how would trade look if each country had had a constant distribution of spending across countries, and growth rates were what they were historically? The second question is roughly equivalent to: How much of the change in trade flows could we predict if we knew expenditure growth rates for each country and nothing else?

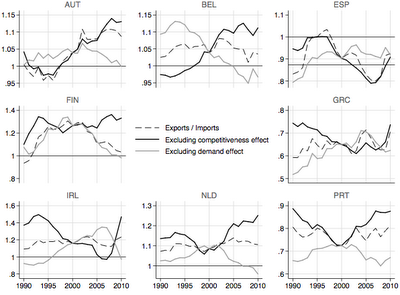

The key results are in the figure below. Look particularly at Germany, in the middle right of the first panel:

The dotted line is the actual ratio of exports to imports. Since Germany has recently had a trade surplus, the line lies above one -- over the past decade, German exports have exceed German imports by about 10 percent. The dark black line is the counterfactual ratio if the division of each county's expenditures among various countries' goods had remained fixed at their average level over the whole period. When the dark black line is falling, that indicates a country growing more rapidly than the countries it exports to; with the share of expenditure on imports fixed, higher income means more imports and a trade balance moving toward deficit. Similarly, when the black line is rising, that indicates a country's total expenditure growing more slowly than expenditure its export markets, as was the case for Germany from the early 1990s until 2008. The light gray line is the other counterfactual -- the path trade would have followed if all countries had grown at an equal rate, so that trade depended only on changes in competitiveness. When the dotted line and the heavy black line move more or less together, we can say that shifts in trade are mostly a matter of aggregate demand; when the dotted line and the gray line move together, mostly a matter of competitiveness (which, again, includes all factors that cause people to shift expenditure between different countries' goods, including but not limited to exchange rates.)

Woj’s Thoughts - If correct, this explanation for global trade imbalances would certainly throw a wrench in standard, mainstream theories that assume prices and exchange rates respond to alleviate any imbalances. Clearly greater relative income growth should lead to larger imports relative to exports. Using a sectoral balances approach, the question is why doesn’t the boost to aggregate demand from rising trade surpluses alter prices and income in a manner that creates convergence? I certainly don’t expect the changes to happen quickly, but remain of the view that some institutional factors (e.g. tax policy, financial regulations) likely encourage diverging prices and incomes.

2) Hoenig: A Better Alternative to Basel Capital Rules by Thomas Hoenig via The Big Picture

Basel III is intended to be a significant improvement over earlier rules. It does attempt to increase capital, but it does so using highly complex modeling tools that rely on a set of subjective, simplifying assumptions to align a firm’s capital and risk profiles. This promises precision far beyond what can be achieved for a system as complex and varied as that of U.S. banking. It relies on central planners’ determination of risks, which creates its own adverse incentives for banks making asset choices.

3) S&P: Australia is Spain in waiting by Houses and Holes @ MacroBusiness

Australia must find a Budget surplus before 2014 or it will lose its AAA rating, according Kyran Curry, S&P sovereign analyst via the AFR:

“If there’s a sustained delay in returning the balance to surplus, as the economy gathers momentum and as people start spending again, as the import demand picks up and current account blows out, we might not see the government’s fiscal position as being strong enough to offset weaknesses on the external side and that’s what worries us…Australia’s already, as we see it, got some credit metrics that are right off the scale when it comes to assessing Australia’s external position…It’s got high levels of external liabilities, it’s got very weak external liquidity and that basically means the banks are very highly indebted compared to their peers…For us, we look to Spain, which was Australia’s closest peer four or five years ago in terms of having a very strong fiscal position, very similar to what Australia has at the moment, its external position was weaker, like Australia’s, and it got routed very quickly…The government needed to provide support to the banks, it had to shore up growth in the economy and its debt levels more than doubled…We can see that happening in Australia’s case.”

Woj’s Thoughts - Contrary to popular perception and especially the Market Monetarist crowd, I’ve been arguing that Australia is facing serious headwinds that will end its impressive growth streak. In this context, Spain offers a reasonable comparison considering its high levels of private debt, housing bubble and high level of external liabilities prior to the current crisis. Having a sovereign currency permits Australia more scope in terms of policy responses, however the current government seems keen on following Europe’s approach. If the Australian government attempts to “find a Budget surplus before 2014,” it may keep its AAA rating while almost certainly exacerbating the downward spiral.

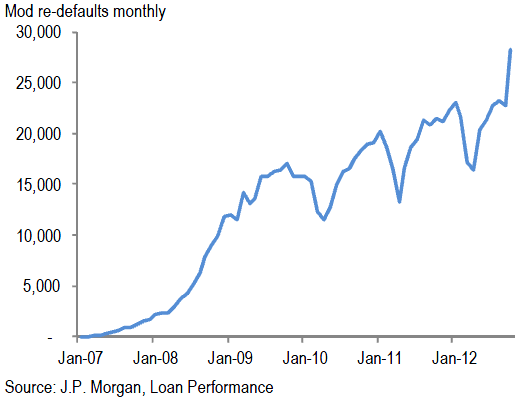

4) Borrowers with modified mortgages re-default as homes re-enter shadow inventory by Walter Kurtz @ Sober Look

We are therefore seeing a sharp rise in re-defaults from modified mortgages.

This is telling us that mortgage modification programs have not been very successful, as the probability of re-default rises. By modifying mortgages, banks in many cases are simply kicking the can down the road - and now some are writing down these mortgages (which may be what is driving the higher charge-off numbers). We are therefore seeing an increase in delinquencies, but mostly among modified mortgages and concentrated in sub-prime portfolios.

Woj’s Thoughts - Bad news for banks and the government. Mortgage modifications were simply not enough for many homeowners who remain underwater and without the requisite income and/or savings to seemingly ever repay the entire loan. If this new wave of re-defaults persists, as JP Morgan expects, housing prices and bank earnings may return to a downward trend.

5) China's Economic Growth: A Different Storyline by Timothy Taylor @ Conversable Economist

When I chat with people about China's economic growth, I often hear a story that goes like this: The main driver's behind China's growth is that it uses a combination of cheap labor and an undervalued exchange rate to create huge trade surpluses. The most recent issue of my own Journal of Economic Perspectives includes a five-paper symposium on China's growth, and they make a compelling case that this received wisdom about China's growth is more wrong than right.

For example, start with the claim that China's economic growth has been driven by huge trade surpluses. China's major economic reforms started around 1978, and rapid growth took off not long after that. But China's balance of trade was essentially in balance until the early 2000s, and only then did it take off. Here's a figure generated using the ever-useful FRED website from the St. Louis Fed.

Woj’s Thoughts - I always have a soft spot for arguments, backed by data, that undermine the mainstream opinion. Although I continue to side with Michael Pettis on the forthcoming rapid slowdown in China’s GDP growth, I agree that growth will persist and lead to a much higher standard of living in the future.

Greece has effectively defaulted again, for what I believe is now the fourth time in the past 3 years. Here are highlights from the full Eurogroup statement on Greece (h/t Delusional Economics).

The Eurogroup noted that the outlook for the sustainability of Greek government debt has worsened compared to March 2012 when the second programme was concluded, mainly on account of a deteriorated macro-economic situation and delays in programme implementation

...

Against this background and after having been reassured of the authorities' resolve to carry the fiscal and structural reform momentum forward and with a positive outcome of the possible debt buy-back operation, the euro area Member States would be prepared to consider the following initiatives:

• A lowering by 100 bps of the interest rate charged to Greece on the loans provided in the context of the Greek Loan Facility. Member States under a full financial assistance programme are not required to participate in the lowering of the GLF interest rates for the period in which they receive themselves financial assistance.

• A lowering by 10 bps of the guarantee fee costs paid by Greece on the EFSF loans.

• An extension of the maturities of the bilateral and EFSF loans by 15 years and a deferral of interest payments of Greece on EFSF loans by 10 years. These measures will not affect the creditworthiness of EFSF, which is fully backed by the guarantees from Member States.

• A commitment by Member States to pass on to Greece's segregated account, an amount equivalent to the income on the SMP portfolio accruing to their national central bank as from budget year 2013. Member States under a full financial assistance programme are not required to participate in this scheme for the period in which they receive themselves financial assistance.The Eurogroup stresses, however, that the above-mentioned benefits of initiatives by euro area Member States would accrue to Greece in a phased manner and conditional upon a strong implementation by the country of the agreed reform measures in the programme period as well as in the post-programme surveillance period.

While I fully expect the market and economic blogosphere to cheer this new agreement, I remain convinced that this deal will be as equally unsuccessful as the previous three (not including the many failed agreements for other countries). From my perspective it is not surprising that Greece’s economic situation has worsened during the past year. What is surprising is the Eurogroup’s ability to commend Greece’s efforts and push to strengthen those previous efforts that have resulted in an increasingly unsustainable economic and political environment.

This agreement, once again, does not actually reduce sovereign debt outstanding but, instead, reduces the interest rate and extends the maturity of previous loans. Although this eases the debt burden ever so slightly, the conditionality of further structural adjustment practically ensures the economy will continue to dramatically underperform. This declining growth will continue to offset attempts to reduce the budget deficit or debt-to-GDP ratio. Considering the lofty expectations for Greece’s economy and budget that accompany this agreement, I feel confident in predicting that a future agreement will read:

The Eurogroup noted that the outlook for the sustainability of Greek government debt has worsened compared to November 2012 when the fourth programme was enacted, mainly on account of a deteriorated macro-economic situation.

Europe is clearly determined to continue kicking the can down the road. Despite the continued optimism regarding each new agreement, the economic reality is that unemployment keeps rising and growth remains in decline, especially for peripheral Europe. The parade of ineffective agreements is far from over.

Related posts:

ECB's Changing Philosophy is Good for Bond Holders but Bad for the Economy

ECB's Means (Lost Decade With High Unemployment) To An End (Structural Reform)

Europe's Leaders Should Learn From Game of Thrones

Unending Subordination of Private Creditors Continues

Yesterday evening, Daniel Kuehn had the following to say in a post about Endogenous money:

I think the whole idea of endogenous money is vastly overrated and the idea of exogenous money is vastly underrated.

...

If you want to say central banks care about interest rates, I'm fine with that. If you want to say that interest rates impact aggregate demand and that influences the broader definitions of the money supply, I'm fine with that. But monetary policy is still done by buying and selling high powered money (as far as I know - I've never talked to someone at the OMO desk), and it's done that way because while causality could run both ways (think of the old use of the discount window or Bagehot's dictums as an example of interest rates "causing" money creation), that's not how it works. Of course there is some target interest rate in mind (and THAT is only what gets churned out of some target inflation rate) - but you buy and sell stuff at the OMO desk because it causes that target interest rate to come to fruition.

My initial response in the comments was that:

Endogenous money is typically about much more than the manner by which central banks perform OMOs. You are correct that central banks typically buy and sell high-powered("outside") money to target a federal funds rate. However, a theory of endogenous money would argue that does little to control the inflation rate or aggregate demand within the economy. Instead, private banks create "inside" money (deposits) through lending that adds to aggregate demand and can create inflation. After lending, banks ensure they meet reserve requirements and the Fed ensures the entire banking system has enough reserves to maintain its target interest rate.

From this perspective, a money multiplier with respect to OMOs does not exist. Further, money and money-like instruments can be perceived as non-neutral, even in the long run. In these ways and more, the distinction between the two theories is far greater than you appear to let on.

(Note: Through QE, the Fed has been buying Treasuries and Agency-MBS, which are not forms of high-powered money)

Since then we have been engaged in some good dialogue back and forth about the merits and actual theory of endogenous versus exogenous money.

Separately, Jonathan Finegold has “a few quibbles” with Edward Harrison’s post on “Endogenous Money and Fully Reserved Banking”:

Second, Harrison writes that bank reserves are irrelevant, because credit demand is endogenously determined; this is true, but generally since demand for credit is practically limitless, reserves provide banks with the capital to lend. I don’t find it convincing to interpret the causality from loan origination to reserve provision (that is, banks lend and then the central banks provides the necessary reserves).

To which I responded:

As for the second point, the central bank always provides enough reserves (either through OMOs or the discount window) for the entire banking system to meet its requirements. Banks can also borrow/lend reserves to each other through the inter-bank market. Since the discount window entails an excess fee for banks, it marks the known upper bound at which reserves can always be obtained. Under normal, pre-2008, circumstances the Fed would adjust the total number of reserves in the banking system through OMOs to ensure it met its target interest rate. Now that the banking system has substantial excess reserves, the Fed uses IOER policy to set the interest rate and adjusts the amount of reserves to increase liquidity, shorten asset maturities in the private sector and alter expectations.

The theory of endogenous money is a significant departure from exogenous money and mainstream, neoclassical views. This fact makes its acceptance and understanding by people well-versed in the traditional view all the more difficult. Hopefully others will join in the conversations and help turn the tide!

Suggested Readings:

Understanding The Modern Monetary System @ Monetary Realism

Endogenous Money: What it is and Why it Matters by Thomas Palley

Endogenous money - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Related Posts:

Fullwiler - "The main shortcoming of the money multiplier paradigm"

A Stinging Critique of Monetarism

The Money Multiplier Fairy Tale

During my classes and through reading countless academic papers, I am continuously bombarded with statistical regressions. Frequently the results are claimed to be “statistically significant” based on a small p-value. The implication is that these results should garner more attention and the hypotheses should be presumed true. Results of this kind typically lead to journal publications and often inform policy making.

Unfortunately, the basic intuition laid out above is technically incorrect and likely detrimental. In a recent manifesto, William Briggs displays the truth behind the meaning of p-values. He argues It is Time to Stop Teaching Frequentism to Non-statisticians, from which I offer a couple select passages:

The hunt for publishable p-values is nearly always fruitful. If one cannot find a publishable p-value in one’s data—with the freedom to pick and choose models and test statistics, to engage in “sub-group” and sequen-tial analysis, and so on—then one is being lazy. P-values can and are used to prove anything and everything. The sole limitation is the imagination of the researcher.

(p.4)

Civilians just can’t remember that it is forbidden in frequentist theory to talk of the probability of a theory’s or a hypothesis’s truth. They insist on translating the certainty they have in the value of some test statistic via the p-value to certainty that their hypotheses are true, despite that this is impossible to do so in frequen-tist theory. The result is that too many people are too certain of too many things.

(p.7-8)

The entire paper is worth reading, but the last sentence highlights my main concern. The desire for certainty in academia and policy making cannot overcome the reality of living in an uncertain world. Attributing excessive certainty to our results may increase our hypothesis’ chances of acceptance, but will not alter the likelihood of its being true in practice. In my view, there is a general need for greater humility, especially in academia and public policy. Classrooms are a great place to start.

(h/t Ryan Murphy @ Increasing Marginal Utility)

As an investor and future economist primarily concerned with the role of credit in business cycles, the release of new data always provides for some intriguing reading. Courtesy of Zero Hedge:

As the just released G.19 confirmed, in September, households once again reduced their credit card debt, which declined by $2.9 billion to $852 billion. This was the fourth such decline in six months, confirming that at the discretionary level where banks have supervision over borrowings, the consumer is still nowhere near willing to relever. Where, there was leverage, a lot of it, was once again in the government sector, which funded $13.8 billion of the total $14.6 billion rise in NSA credit, and where non-revolving credit: read loans for Government Motors, at least those that have not been record channel stuffed (as reported previously) and Federal Student Loans, which are now over $1 trillion, rose by $14.3 billion in one month. Of course, the difference between revolving and non-revolving credit is that while banks expect the former to be paid off eventually, Uncle Sam has no such illusions on any low APR debt it hands out to anyone who asks for it (and if the proceeds from student loans are used to purchase iPads, so be it).

Aside from the notion that most new credit growth stems from the federal government (e.g. student loans), the degree to which credit is extended for car purchases/leases remains troubling. When one considers the extension of credit for housing, investments or education, there is a clear path by which that investment could generate positive returns and make future repayment of principal and interest easier. However, when it comes to spending on automobiles (or consumption goods) there is presumably no expectation for a positive return since cars lose a significant portion of their “value” once driven off the lot. Hence auto loans are seemingly granted on the basis that borrowers face short-term liquidity issues or will experience increased future returns from other investments.

Assuming the above mentioned reasons for providing auto loans are largely correct, there is clearly an opportunity for market participants with excess liquidity (e.g banks) to offer loans in hopes of earning a profit. In doing so, the private participants (ideally) also accept the risk of losses stemming from non-repayment. The market price (again, ideally) adjusts to reflect the most current expectations of risk and reward, as seen through supply and demand.

How does this relate back to the government? As most people know, during the financial crisis, the U.S. government took control over General Motors (GM) and placed it through a managed bankruptcy. What many may not be aware of, is that the U.S. government also bailed out and took a controlling stake in Ally Financial Inc., formerly known as GMAC (General Motors Acceptance Corporation). Today that stake remains at ~74% and is even higher if one includes GM’s nearly 10% stake. To demonstrate the importance of Ally to GM, and now Chrysler (the other bailed out auto company), here is a pertinent portion of the 2011 Annual Report:

We financed 79% and 65% of GM's and Chrysler's North American dealer inventory, respectively, during 2011, and 78% of GM's international dealer inventory in countries where GM operates and we provide dealer inventory financing, excluding China.

Given the enormous percentage, it appears Ally’s terms of credit are well below other market participants. While this strategy implicitly held a government backing prior to the crisis, it’s failure has now resulted in an explicit backing from the government (i.e. the public bears the risk).

We could argue over whether or not the federal government should be subsidizing credit at all, but I want to put that debate aside for the moment. If governments are set on encouraging investment and/or consumption through extension of credit at below-market prices, is the auto sector really the most productive use? Is it even close?

Whether or not the auto bailouts were a success, remains an open question for many. Unfortunately the costs associated with Ally Financial, especially the opportunity costs of credit, are often overlooked. Going forward, consideration of the success or failure of the auto bailouts must account for the ongoing costs of directing scarce resources towards that sector and future losses on loans. Hopefully these factors will also play a role in determining how long the current environment is allowed to persist.

Related posts:

Is the Return of Auto Subprime Lending and GM "Channel Stuffing" Connected?

Liberals Demonstrate Conservative Bias for Manufacturing

An American Icon Returns