After furthering understanding of the permanent floor, I discussed how that monetary regime might affect the inflationary effects of the “platinum coin.” Although the debate appears to be dying down, at least momentarily, Simon Wren-Lewis and Frances Coppola (see here, here, and here) have added worthwhile readings.

In concluding my brief series on this topic, I will address questions regarding potential Federal Reserve insolvency and the desirability of permanently practicing monetary policy under a “floor” system. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Q: The Federal Reserve has recently been turning over to the Treasury approximately $80 billion in profits each year, stemming from the yield spread between their assets and liabilities. As the Fed eventually raises interest rates on reserves (assuming the “permanent floor” system remains in place), that yield spread could turn negative, representing losses for the Fed. If the Fed’s capital is entirely drained, can it continue to pay interest on liabilities (e.g. reserves) or must it first be recapitalized? If the latter, does this require Congressional approval, Treasury action, or some other mechanism?

A: Before trying to put forth an answer, I should note that the present likelihood of this scenario becoming a reality is extremely small and would probably be preceded by much higher inflation (and interest rates). As several commenters noted, finding a direct answer to this question is extremely difficult. Courtesy of Dan Kervick:

Here is a 2002 General Accounting Office report that discusses some of these issues:

http://www.gao.gov/assets/240/235606.pdf

From the “Results in Brief” section at the beginning:

The Reserve Banks use their capital surplus accounts to act as a cushion to absorb losses. The Financial Accounting Manual for Federal Reserve Banks says that the primary purpose of the surplus account is to provide capital to supplement paid-in capital for use in the event of loss. Federal Reserve Board officials noted that the capital surplus account absorbs losses that a Reserve Bank may experience, for example, when its foreign currency holdings are revalued downward. Federal Reserve Board officials noted, however, that it could be argued that any central bank, including the Federal Reserve System, may not need to hold capital to absorb losses, mainly because a central bank can create additional domestic currency to meet any obligation denominated in that currency. On the other hand, it can also be argued that maintaining capital, including the surplus account, provides an assurance of a central bank’s strength and stability to investors and holders of its currency, including those abroad. The growth in the Reserve Banks’ capital surplus accounts can be attributed to growth in the size of the banking system together with the Federal Reserve Board’s policy of equating the amount in the surplus account with the amount in the paidin capital account. The level of the Federal Reserve capital surplus account is not based on any quantitative assessment of potential financial risk associated with the Federal Reserve System’s assets or liabilities. According to Federal Reserve officials, the current policy of setting levels of surplus through a formula reduces the potential for any misperception that the surplus is manipulated to serve some ulterior purpose. In response to our 1996 recommendation that the Federal Reserve Board review its policies regarding the capital surplus account, it conducted an internal study that did not lead to major changes in policy.

Based on this paragraph and corresponding discussion, the best current answer is that negative equity would not prevent the Fed from pursuing its desired monetary policy since “a central bank can create additional domestic currency to meet any obligation denominated in that currency.” If the Fed truly desired to maintain a capital surplus, to signal “strength and stability to investors and holders of its currency,” than one option is raising service fees charged to banks. This action would represent a tightening of monetary policy, but that could be desirable at the time.

If that course is not pursued, the other plausible action appears to be a Congressionally approved capital transfer from the Treasury. Although this action could be contended by politicians that oppose the Fed, the reality is that failure to provide capital would not alter the Fed’s ability to act or remain independent. Furthermore, a contentious Congressional battle on this otherwise insignificant matter could undermine the Dollar’s status as a reserve currency (similar to the debt ceiling debates). Provided this view is reasonably accurate, there appears little reason to fear the Fed losing its capital or as some argue, becoming ‘insolvent’.

Q: If the Fed leaves the zero lower bound (ZLB), is there any good reason to keep reserves in chronic excess?

A: Yes. An “interest-on-reserves regime” or “permanent floor”, where reserves are kept in chronic excess, allows the Fed to exogenously determine the monetary base AND interest rate. Therefore, if the Fed wishes to exit the ZLB it must either sell treasuries and Agency-MBS until excess reserves are practically eliminated (reverse QE) or increase the interest rate on reserves (IOR) to set a floor for the interbank market (target rate).

Given the response of asset markets to QE, the former option poses the risk of asset market deflation and possible spillovers to the real economy. To clarify, these arguments suggest there are good reasons to keep reserves in chronic excess but does not imply the Fed should permanently adjust to a “floor” system.

The “platinum coin” has been shot down as a potential response to hitting the debt ceiling, but it has made a substantial impact in expanding debates about how our modern monetary system actually functions. One of these topics, the “permanent floor,” will likely remain a prominent topic of macroeconomic arguments for at least as long as the Fed operates monetary policy within that system. The fantastic recent discussion on this subject has vastly improved my understanding of the policy’s intricacies, but has not altered my initial impression about the future practice of monetary policy (emphasis added):

An “interest-on-reserves regime” appears likely to rule monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

Special thanks are owed to Tom Hickey (Mike Norman Economics) and Michael Sankowski (Monetary Realism) for posting links to this blog. For their contributions through comments, I would also like to thank Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax.

While continuing my own effort to further understanding of the permanent floor, related posts keep rolling in. Unfortunately my earlier post was remiss in recognizing contributions by Ashwin Parameswaran and Frances Coppola even prior to the outburst. A major player from the start, Steve Randy Waldman has once again raised the bar for a confederacy of dorks. David Beckworth, Peter Dorman, Nick Rowe and Stephen Williamson (see here, here, and here) also share their thoughts.

Once again, I won’t spend much time recapping the major points of contention. My intent is to highlight a few questions that came to mind while reading but, in my opinion, were not adequately addressed. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Question(s): What are the inflationary effects, if any, of the “platinum coin” both at and away from the zero lower bound (ZLB)? Under a “permanent floor” vs. “corridor” system?

Answer(s): As stated previously:

When the Treasury deposits a $1 trillion platinum coin at the Fed, the Fed credits the Treasury’s account with $1 trillion in reserves. These reserves, however, are not counted in the monetary base since the Treasury's account does not count as reserve balances in circulation. The simple action of depositing a platinum coin at the Fed therefore has no direct impact on the economy that would require sterilization*. In fact, the primary (sole?) purpose of this exchange is to allow the Treasury (Congress) to spend without requiring debt sales that would exceed the debt limit.

The platinum coin, in itself, is therefore not inflationary regardless of whether or not the economy is at the ZLB. The story, however, need not end there. Unburdened by the obligation to sell debt when deficit spending occurs, government deficit spending (up to the coin’s value) will directly increase the monetary base by adding reserves to the private banking system (reserves in circulation).

Operating within a “permanent floor” system, the Fed can maintain control of interest rates by paying a positive interest rate on reserves (IOR) AND elect whether or not to sterilize the monetary base expansion. If sterilized, the Fed could actually increase interest income in the private sector by selling assets with a higher yield. This would have an inflationary effect, though it may be offset by portfolio rebalancing. If left unsterilized, the monetary base expansion would likely generate asset price inflation and rising inflation expectations, at least in the short-run, given recent experiences with QE. In either case, the increase in deficit spending (otherwise not permitted by the debt limit) should ensure an overall inflationary bias.

Under the old monetary regime (pre-2008; “corridor” system), the Fed would probably sterilize the expansion by selling Treasuries (at least initially). Although the monetary base and interest rate are left unchanged, the deficit spending results in the private sector gaining net financial assets (NFAs; e.g. Treasuries). This is exactly the same result we see today! The only tweak is that the Fed, not Treasury, becomes the supplier of Treasuries.

Still under the old monetary regime, if left unsterilized, the expansion of the monetary base would push interest rates to the ZLB. The inflationary effects of the downward pressure on short-term rates depends on the time period in consideration (often short-term) and the degree of influence from several potential cross-currents (in no particular order):

1) Decreases interest income - deflationary

2) Weakens the currency - inflationary

3) Lowers debt service costs to borrowers - inflationary

4) Increases bank lending - inflationary

5) Raises inflation expectations - inflationary

The above list is in no way exhaustive, but does suggest an inflationary bias. Countering this view, Scott Sumner states:

higher interest rates are inflationary. They increase velocity. If you don’t believe me, check out interest rates and velocity during any extremely high inflation episode. When rates rise, inflation usually rises.

Perhaps surprisingly, I do believe that interest rates and velocity show a relatively strong correlation over time. What I disagree with is the direction of causation that Sumner ascribes to this relationship. From my perspective, decreasing velocity implies decelerating bank lending and/or declining inflation expectations. Witnessing either of these factors would encourage the Fed to lower interest rates, hence any causation runs in the opposite direction of Sumner’s claim. Determining whether interest rates or velocity tends to move first would be enlightening, if feasible, but for now I’ll conclude that lower interest rates are inflationary.

Under any of these circumstances, the transaction entailing a platinum coin between the Treasury and Fed, in and of itself, is not directly inflationary*. However, presuming the platinum coin is accompanied by greater deficit spending, some inflation will stem from the growth of private NFAs regardless of the monetary regime and sterilization decision. Corresponding monetary base expansion will also likely display an inflationary bias, unless the Fed elects to sterilize the expansion under the old “corridor” system. The platinum coin is therefore always inflationary.

Special thanks for their contributions through comments are still owed to Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax. Stay tuned for at least one more post in this series.

*it may indirectly impact the economy by altering expectations

Several months ago I wrote (emphasis added):

The Federal Reserve’s decision to implement an “interest-on-reserves regime” has clearly been beneficial in permitting the use of previously conventional measures for unconventional purposes, including the provision of liquidity and “financing” of federal budget deficits. Eliminating the payment of interest-on-reserves will not prevent the Fed from continuing to use open market operations in this manner, as long as the Fed Funds rate remains at zero. However, departing from this new regime will ensure that any future rate hikes be preempted by a reversal of the balance sheet expansion (or excess sale of Treasuries).

…

Given that any decision to cease paying interest-on-reserves would likely be temporary and the potential benefit is limited, there is seemingly little reason for the Fed to change course. An “interest-on-reserves regime” appears likely to rule monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

That prognostication, more recently made by Steve Randy Waldman, has generated an intense online debate about monetary operations, base money, the platinum coin and the so-called “permanent floor.” Waldman (also here and here) and Paul Krugman (see here and here) have been the major players, but others including Cullen Roche (see here and here), Scott Sumner (see here and here), Izabella Kaminska, Tim Duy (see here, here, and here), Merijn Knibbe, Ashwin Parameswaran, Greg Ip, and Scott Fullwiler (the foremost expert on the subject) have jumped in the ring. For monetary dorks/nerds, myself included, the discussion has been extremely interesting and illuminating.

Since so much has already been written on the matter, I won’t spend much time recapping the major points of contention. My intent is to highlight a few questions that came to mind while reading but, in my opinion, were not adequately addressed. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Question(s): Assuming a “platinum coin” example, Paul Krugman says:

“right now it makes no difference: financing the government by selling T-bills with zero yield, and financing it by making a deposit at the Fed, which either adds to the monetary base or sells some of its zero-yield assets, has, um, zero implication for anything except some peoples’ blood pressure.

But what happens if and when the economy recovers, and market interest rates rise off the floor?

There are several possibilities:

1. The Treasury redeems the coin, which it does by borrowing a trillion dollars.

2. The coin stays at the Fed, but the Fed sterilizes any impact on the economy, either by (a) selling off assets or (b) raising the interest rate it pays on bank reserves

3. The Fed simply expands the monetary base to match the value of the coin, an expansion that mainly ends up in the form of currency, without taking offsetting measures to sterilize the effect.”

First, does financing the deficit by making a deposit at the Fed add to the monetary base? Second, what impact on the economy does the coin have that requires ‘sterilizing’? Third, if the monetary base expands, will the expansion mainly end up in currency form?

Answer(s): When the Treasury deposits a $1 trillion platinum coin at the Fed, the Fed credits the Treasury’s account with $1 trillion in reserves. These reserves, however, are not counted in the monetary base since the Treasury's account does not count as reserve balances in circulation. The simple action of depositing a platinum coin at the Fed therefore has no direct impact on the economy that would require sterilization*. In fact, the primary (sole?) purpose of this exchange is to allow the Treasury (Congress) to spend without requiring debt sales that would exceed the debt limit. This seemingly harmless subversion of federal spending requirements actually holds great significance regarding the roles of private banking and the Fed in our current monetary system.

Free from the obligation to sell debt when deficit spending occurs, the Treasury would directly increase the monetary base as spending adds reserves to the private banking system (reserves in circulation). If the Fed was not operating under a “permanent floor” system or at the zero lower bound (ZLB), this would require the Fed to sterilize the effect either through asset sales or debt sales. Since the Fed would have reduced its balance sheet to pre-2008 levels, asset sales would be relatively limited in quantity. The Fed is also legally prohibited from selling its own debt, so it’s seemingly fortunate that the Fed has been permitted to issue time deposits since September 2010 (h/t jck in comments). Aside from the slightly altered roles in affecting the monetary base, it’s important to note that the Fed would become the primary payer of interest in this scenario. Although this has no impact on a consolidated government balance sheet (combining the Treasury and Fed), it would likely require the Fed to either indefinitely operate with negative equity or receive substantial transfers of capital from the Treasury (see forthcoming post on the logistics of Fed ‘insolvency’).

While the Fed’s role and independence is diminished by these actions, the role of private banks could potentially be reduced by far more. With government spending unconstrained by debt sales (and a compliant Fed), the government could subvert the reign of private banks as primary issuers of money. This would drastically reduce the profitability of banks and their power to influence government actions. Recognition of these potentially dramatic changes to the financial system may have provided the impetus for the Fed’s decision to shoot down the “platinum coin.”

Returning to Krugman’s third scenario and the third question mentioned above, let’s assume the Treasury increases the monetary base by spending reserves into the system and the Fed wishes to raise interest rates. If the Fed does not want to operate under a “permanent floor” system, then it must sterilize the monetary base expansion (or remain at the ZLB).

However, if the Fed elects to operate under a “permanent floor” system, then it can raise interest rates by raising the interest rate on reserves (IOR) AND decide whether or not to sterilize the increase in the monetary base. If the Fed chooses not to sterilize, the rising monetary base will consist of either non-interest bearing currency or interest-bearing reserves. Assuming that the expansion “ends up mainly in the form of currency” requires that banks (and individuals) either cannot exchange currency for reserves or prefer a non-interest bearing asset to an interest-bearing one. Since Waldman informs us that “holders of currency have the right to convert into Fed reserves at will (albeit with the unnecessary intermediation of the quasiprivate banking system)” and the latter constraint is irrational (certainly for large quantities), the expansion will almost certainly consist mainly of reserves.

As this post is already bordering on (crossed?) being of excessive length, the remaining questions and answers will be temporarily postponed. Special thanks for their contributions through comments are owed to Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax.

*it may indirectly impact the economy by altering expectations

Last year I took a chance and threw my own projections into the ring. Similar to Byron Wien and Edward Harrison, I mostly selected events that were widely seen as having a low probability (less than 33%) but which I believed held a greater than 50% chance of occurring. Let’s see how I did...

1) Greece leaves the Euro - As the year progresses the Greek economy continues to contract and unemployment continues to rise, surpassing 50% for youth. This combination of factors offsets attempts to reduce the budget deficit as the country repeatedly misses EU and IMF required targets. Despite potential for further bailouts, the Greek people finally decide the consequences of tied promises outweigh the benefits of remaining in the Euro. Greece defaults on all debts, returning to a heavily depressed drachma.

Result - Wrong (0-1). During 2012, Greece was successful in reducing its budget deficit by 30 percent and staying in the Eurozone. This success was in large part due to further defaults on public debt and another bailout. Unfortunately for the Greek people. the price of these efforts remains extraordinarily high. The economy may have contracted as much as 6.5 percent in 2012, the fifth year of recession, according to forecasts in the 2013 budget. Meanwhile both the general and youth unemployment rates continue to soar, reaching ~27 percent and ~58 percent, respectively. At this point Greece is clearly in the midst of a Depression and showing no signs of recovering anytime soon. Greek tolerance of increasing unemployment and decreasing prosperity remains a surprise, although radical political parties have been gaining support. For now Greece remains in the Eurozone, but a future exit remains likely.

2) Italy and Spain lose access to credit markets - A Greek default raises concerns about the potential for creditors to face actual losses on EU sovereign debt. The ECB’s measured efforts are not strong enough to overcome fear and concern about future growth in Italy and Spain. Deep recessions take hold in both countries, pushing deficits higher.

Result - Wrong (0-2). A Greek default and concerns about the European economy weighed heavily on EU sovereign debt during the first half of the year. By the summer, ten-year bond yields in Spain and Italy were at 7.75 percent and 6.75 percent, respectively, and rising. With the countries at risk of losing access to credit markets, ECB President Mario Draghi came forth with a plan to cap sovereign interest rates using open-ended outright monetary transactions (OMT). Draghi’s threat was enough to generate a 180 degree turn in EU sovereign debt markets, but nowhere near enough to turn around the economies. Italy and Spain both returned to recession this past year, pushing fiscal deficits and unemployment higher. While Italy’s unemployment rate remains closely tied to the EU-wide level of ~11 percent, Spain’s general and youth unemployment rates have quickly caught up to Greece’s levels. Eventually Draghi’s Liquidity Bluff Will Be Called, potentially sooner rather than later as a strengthening euro may reignite the EU crisis.

3) The Eurozone enters recession - Practically the entire Eurozone falls into recession, including the likes of France and Germany. A deteriorating economic outlook causes deficit estimates to be raised across the board, facilitating credit rating downgrades. Agreements for greater austerity fail to stem the tide and other attempts to kick the can down the road are pursued.

Result - Correct (1-2). The euro zone economy contracted 0.2 percent in the second quarter and 0.1 percent in the third, meeting the technical definition of a recession. The fourth quarter drop is looking even worse following recent news that Germany saw output shrink 0.5 per cent between October and December. Although Germany managed to run a slight fiscal surplus, at the expense of growth, Spain’s budget deficit probably exceeded 9 percent for a fourth year in 2012. The first half of the year did witness credit downgrades and austerity agreements, but Draghi’s big kick at the end of summer pushed any further actions into future years.

4) China’s GDP growth falls below 7% - As exports to Europe contract, the busting of China’s housing bubble continues unabated. Expectations for massive monetary easing in Europe and the US, along with fear of flare ups in the Middle East sets a floor under energy and food commodity prices. Monetary easing and fiscal stimulus in China are applied too slowly to prevent growth from slowing below the supposedly necessary 8%. (Note: This will be not be considered a hard-landing, which I deem growth below 5%. That may come in 2013, but for 2012 most economists/analysts will be able to maintain expectations of a soft-landing.)

Result - Wrong (1-3). During the third quarter China’s growth rate slowed to a three-year low of 7.4 percent, but the year-end tally will probably be around 7.7 percent. As growth slowed and housing prices fell early in the year, the government took action to allow a smoother transition between governments. Fiscal stimulus has pushed growth and inflation higher in the last few months, but at the expense of rebalancing the economy toward consumers for future sustainability.

5) Oil prices will spike above $120, finish year below $90 - (Using WTI crude prices, currently ~$102) At some point during the year Iran attempts to block the Strait of Hormuz. Further attempts to overthrow governments in the Middle East, possibly some that only recently gained power, hit the headlines again. Combined with global monetary easing, oil prices will move higher and gasoline will once again hit $4 per gallon in the US. These higher prices will exaggerate the reduction in global demand for other goods and push growth lower. As fears of a global recession take over, oil prices will fall, finishing the year down more than 10%.

Result - Wrong, but close (1-4). Fears about Iran and the Middle East never really materialized this year but that did not prevent a wild ride in oil prices. After rising to over $113 in April, WTI crude prices dropped all the way down to $80 in August (daily price history). A rally in the last week of the year brought the closing price slightly back above $90. Brent crude prices diverged significantly from WTI in 2012, keeping gas prices at the pump high throughout the summer. Gas prices peaked at $3.94, not quite $4, but nevertheless reached a record-high average of $3.62 per gallon.

6) US enters recession in 2nd half - Despite higher 4th quarter GDP in 2011, the lower savings rate and energy prices are unlikely to add much growth in 2012. With Europe contracting and China slowing down more than expected, US exports will take a hit. Extensions of the payroll tax cut and unemployment benefits will help ensure the federal deficit holds above 8%. Housing prices will continue to fall (based on Case-Shiller) causing the savings rate to once again reach 5%. By the end of 2012, the US will be in a recession (although NBER may not confirm this until 2013).

Result - Wrong (1-5). Despite Europe contracting, China slowing down and the federal deficit dropping to 7% (still over $1 trillion), US GDP growth remained positive throughout 2012. After falling to 1.3 percent in the second quarter, annualized GDP growth jumped to 3.1 percent in the third quarter. Although current estimates for fourth quarter GDP are below 1 percent, the US is most likely not in a recession at this time. Partially behind the positive growth was the impact of housing prices rising over 5 percent and the savings rate remaining below 4 percent.

7) Federal Reserve extends forecasts for ~0% rates until 2015 - As growth in the US weakens once again and the global economy slows, expected inflation over the next ten years (based on Cleveland Fed estimates) will fall towards 1%. With unemployment holding steady around 9%, the Fed will move it’s forecasts for the first interest rate hike out to 2015. (Some form of QE3 is also likely, but aside from promoting short-term speculation, the effects on growth are likely to be muted.)

Result - Correct (2-5). Expected inflation over the next ten years fell consistently during the course of the year to approximately 1.5 percent (chart below). Although unemployment improved materially, dropping below 8 percent, the Federal Reserve still felt the urge to step up monetary stimulus. On September 13th, 2012, the FOMC extended its projections for maintaining “exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate...at least through mid-2015” while enacting a plan to purchase “additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month” indefinitely. Since QEternity was insufficient to boost growth, the Fed also enacted QE4 to raise the rate of balance sheet expansion.

8) President Obama will win re-election - Generally a weakening economy has been poor for incumbents but this time will be seen as abnormal circumstances. The troubles in Europe and high unemployment will actually spark desire for a more interventionist government. Given the choice between Obama and Romney, the President will win re-election by a slim margin (2% or less).

Result - Correct (3-5). President Obama crushed Romney in the 2012 election based on the electoral college, however the popular vote was decided by less than 3 percent.

9) The US dollar rises over 5% - (Based on dollar index) In spite of QE efforts and another sizable deficit, the US dollar retains its safe haven status. As fears of European defaults spread and China’s slowing growth impacts commodity prices, the dollar will continue to trend higher.

Result - Wrong (3-6). As fears spread about European default and a slowdown in China, the dollar rose several percent into the summer months. When those fears were assuaged by politicians, not economic data, the euro began a strong rally. By the end of the year, the dollar had essentially finished flat.

10) Bonds outperform stocks - The consensus once again favors stocks, although US Treasuries have now outperformed stocks over the past 1, 10 and 30 year horizons. With global growth slowing, inflation expectations will fall. Before this bull market in bonds ends, 10- and 30-year Treasuries may reach 1% and 2%, respectively.

Result - Wrong (3-7). Slowing global growth, falling inflation expectations and stagnating corporate earnings were not enough to deter stocks from a very strong performance in 2012. The Bernanke put morphed into a proactive Fed determined to push asset prices higher and succeeding to the tune of over 15 percent. While stocks were riding towards new highs, the bull market in bonds also remained intact. The 10- and 30-year Treasuries hit their respective lows of 1.43 and 2.46 during the summer before heading higher into year end. Ultimately 10- and 30-year Treasuries last year posted returns of only 3 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively.

That’s the end of it. 3-7 is certainly a bit of a disappointment, especially given the direction of events through the first half of the year. That being said, the logic behind each prediction was sound and far more on target than the end result suggests. My main takeaway is that politicians are far more determined to maintain the status quo than I had expected. The underlying economic (and social) problems have once again been kicked down the road for future governments to handle. As long as that pattern holds, current optimism and modest growth can persist for another couple years.

My hope is to have Predictions for 2013 out by the end of next week. Stay tuned.

Nick Rowe recently discussed the Bank of Canada’s success and failure in inflation targeting versus maintaining a stable NGDP growth path. Looking at Rowe’s charts, Stephen Gordon points out that during the period in question:

producer prices (roughly approximated by the GDP deflator) grew much more quickly than consumer prices (roughly approximated by the CPI).

If the Bank of Canada were to begin targeting NGDP in the future, it would effectively be altering the primary measure of inflation in its goal. This leads Gordon to beg the question, What should a central bank do when producer and consumer prices diverge?

My (possibly incomplete) understanding is about how inflation affects welfare is on its effect on the price of consumption goods, especially in a world where nominal wages are slow to adjust. So it makes sense to me to make consumer prices the focus of attention and let producer prices go.

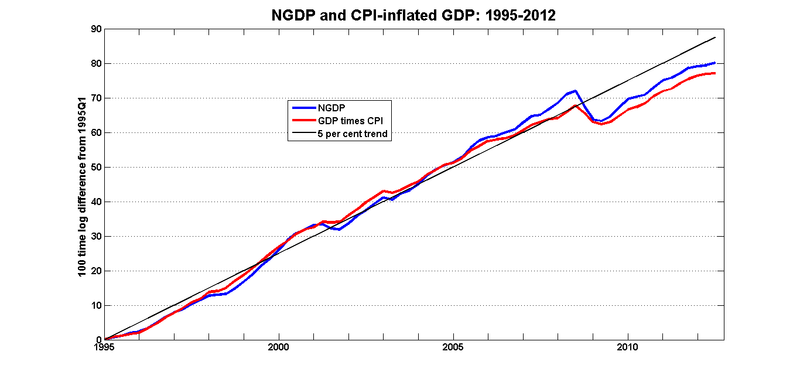

I'm not sure how to interpret this next graph, but I made it and I may as well post it. It compares NGDP with the series you get when you multiply real GDP by the CPI. I guess it's the counterfactual NGDP series for the scenario where producer prices and CPI stayed together:

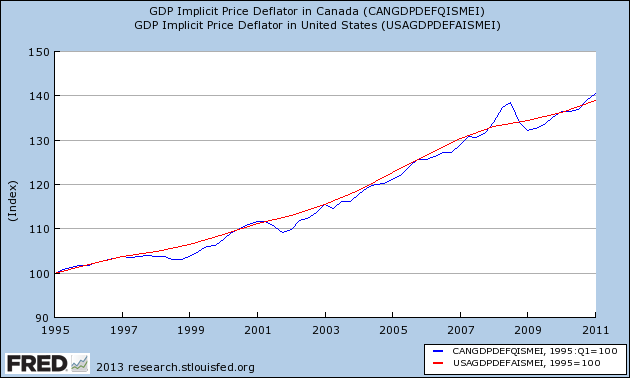

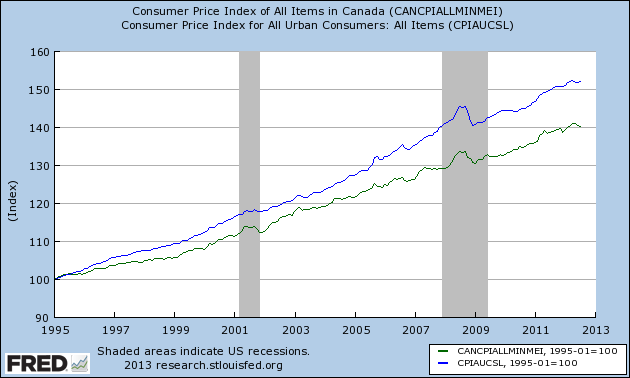

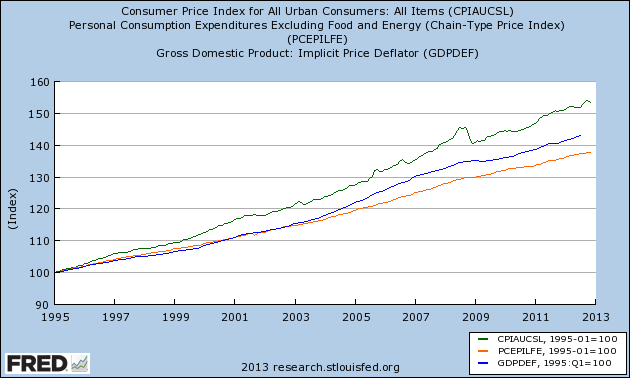

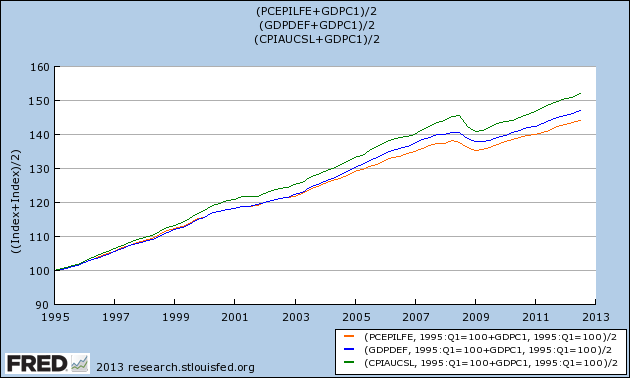

Gordon and Rowe’s focus is strictly on Canada, but given the hype surrounding NGDP targeting in the US, it might prove interesting to compare similar data. The following charts compare the GDP deflator and CPI between both countries over the same time period:

While producer prices between the two countries remained closely tied throughout the period, consumer prices in the US began diverging from their Canadian counterpart immediately and the gap continues to widen today. Shifting focus to the U.S., the data series for consumer and producer prices are combined into one chart. Returning to discussion of central bank policy, as well, it’s important to include the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, core-PCE: The inclusion of core-PCE helps resolve the discrepancy between consumer prices in Canada and the US. Of note is the dramatic difference between CPI and core-PCE over the past two decades. As I understand Fed policy, CPI (or PCE) is too volatile a target due to the wide swings in food and energy prices. Over time, however, the total and core measures are expected to converge. Depending on the time frame one assigns to the long-run (~18 years seems reasonable), the double-digit difference suggests that Fed policy has been looser than many believe. The Fed’s success has been limited to targeting core inflation, while food, energy and asset prices (not accounted for in CPI) have drifted significantly higher.

The inclusion of core-PCE helps resolve the discrepancy between consumer prices in Canada and the US. Of note is the dramatic difference between CPI and core-PCE over the past two decades. As I understand Fed policy, CPI (or PCE) is too volatile a target due to the wide swings in food and energy prices. Over time, however, the total and core measures are expected to converge. Depending on the time frame one assigns to the long-run (~18 years seems reasonable), the double-digit difference suggests that Fed policy has been looser than many believe. The Fed’s success has been limited to targeting core inflation, while food, energy and asset prices (not accounted for in CPI) have drifted significantly higher.

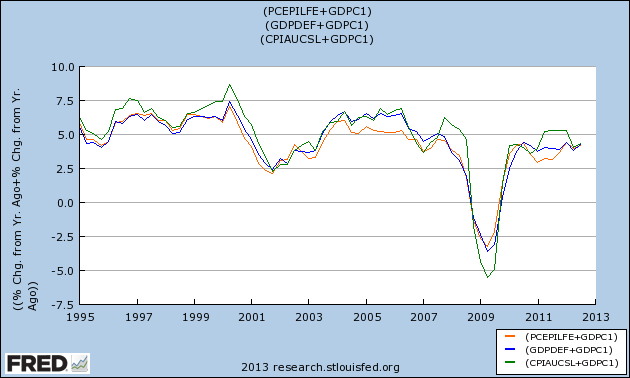

Returning to Gordon’s chart and altering data to depict the US, these last two charts show a “counterfactual NGDP series for the scenario where producer prices and CPI stayed together.”

Regardless of the inflation measure chosen, the Fed’s policy was clearly too loose in the decade preceding the most recent recession. In fact, an interest rate targeting regime focused on core-PCE permitted the Fed to remain looser than it would have been following either of the other indexes.

Regardless of the inflation measure chosen, the Fed’s policy was clearly too loose in the decade preceding the most recent recession. In fact, an interest rate targeting regime focused on core-PCE permitted the Fed to remain looser than it would have been following either of the other indexes.

Gordon concludes with “the question of what happens to the volatility of consumer prices if we adopted NGDP targeting.” Oddly enough, the divergence of core-PCE from the GDP deflator began around the same time the Fed started targeting core-PCE in 2004. Is it possible that the Fed’s actions altered the relationship between core-PCE and the GDP deflator? The similarities between Canada and the US during that period suggests not, but it’s worth considering. Separately, will the stark difference between CPI and core-PCE ultimately correct or has the world entered a new era of food and energy inflation?

My guess is that the volatility of core consumer prices will change only slightly under an NGDP targeting regime, while total consumer prices become far more volatile. Apart from my concerns about the viability of NGDP targeting, its effect on consumer prices raises important questions about wages and welfare costs. Hopefully these potential unintended consequences of NGDP targeting are being carefully considered before such a policy is actually implemented.