For anyone following my blog, you've likely recognized the significant slow down in the number of posts recently. The drop off has not been due to a lack of ideas, but rather to my personal search for a deeper understanding of economics, financial markets and our monetary system. After starting my own blog, with the help of Google reader, I began searching out and reading other economics/financial blogs. Amazed not only by the sheer number but the renowned economists and investors’ blogging, I recognized my knowledge obviously pared in comparison to Nobel Laureates. Although I don't expect to reach that level of knowledge or insight anytime soon (let alone ever), I've taken it upon myself to read and absorb as much knowledge as possible through these blogs and a multitude of books (thanks to my new Kindle). Hopefully this and future posts will prove increasingly valuable and insightful.

Over the past several months, my news sources for economics and financial markets have shifted from CNBC and websites such as TheStreet.com to numerous blogs and books. A primary reason for the shift is the stark contrast between what I view as news that follows the crowd without much insight versus detailed economic and financial analysis by writers willing to buck the trend. Anyone watching basic news channels or CNBC today will hear a great deal of rhetoric from Wall Street and Washington about how the economy is getting back to "normal" (if not there already). Others who follow PIMCO's co-CIOs, Mohamed El-Erian and Bill Gross, will frequently hear discussion of the U.S. economy mired in a "new normal." All this begs the question, what is normal?

Dictionary.com describes normal as conforming to the standard or the common type. So does the economy today represent a normal recovery? As a starting point, we should consider U.S. fiscal and monetary policy. The recession officially ended in June 2009, yet the federal government ran a fiscal deficit over $1 trillion or nearly 9% of GDP in 2010. For 2011, the deficit is expected to be even larger, possibly breaching 10% of GDP. Switching to monetary policy, the Federal Reserve is currently maintaining short-term interest rates at 0-0.25%, a new low for the post World War II era. At the same time, the Fed is moving towards completion of QEII. Since the recession began, the Fed's balance sheet has grown from $800 billion to nearly $2.5 trillion, by purchasing a great deal of securities that hold far greater risk than U.S. Treasuries. A brief look at history makes clear that 10% deficits, zero-interest rates, and quantitative easing are substantially new for the U.S. but are reminiscent of Japanese policy the past two decades.

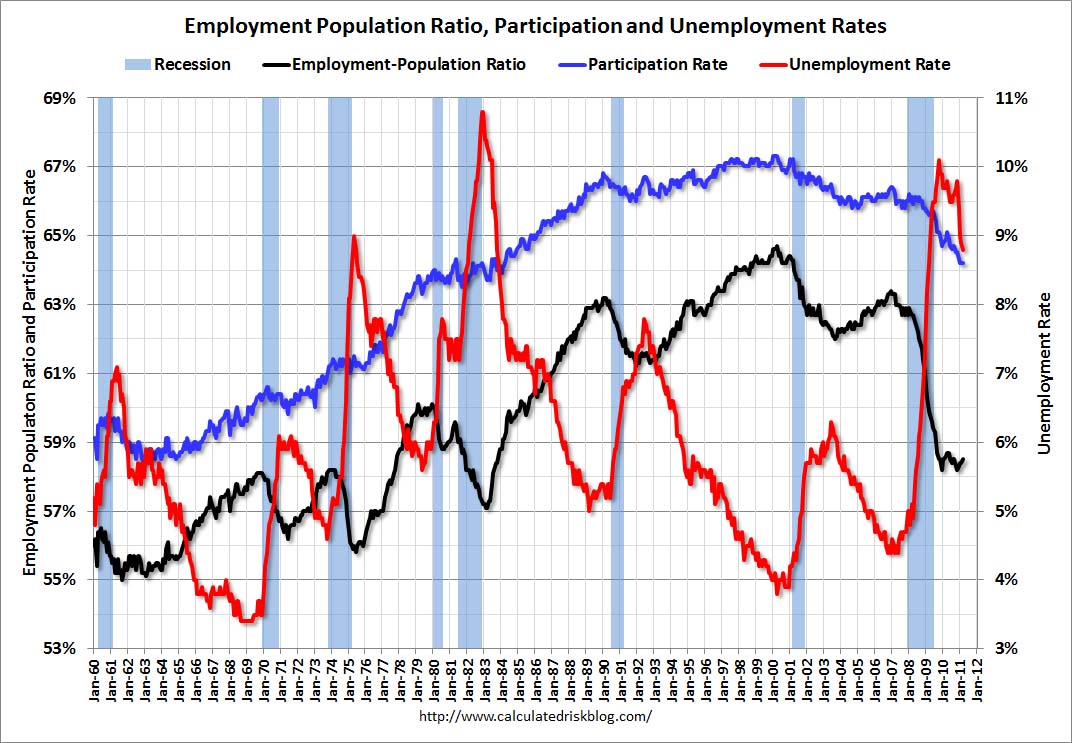

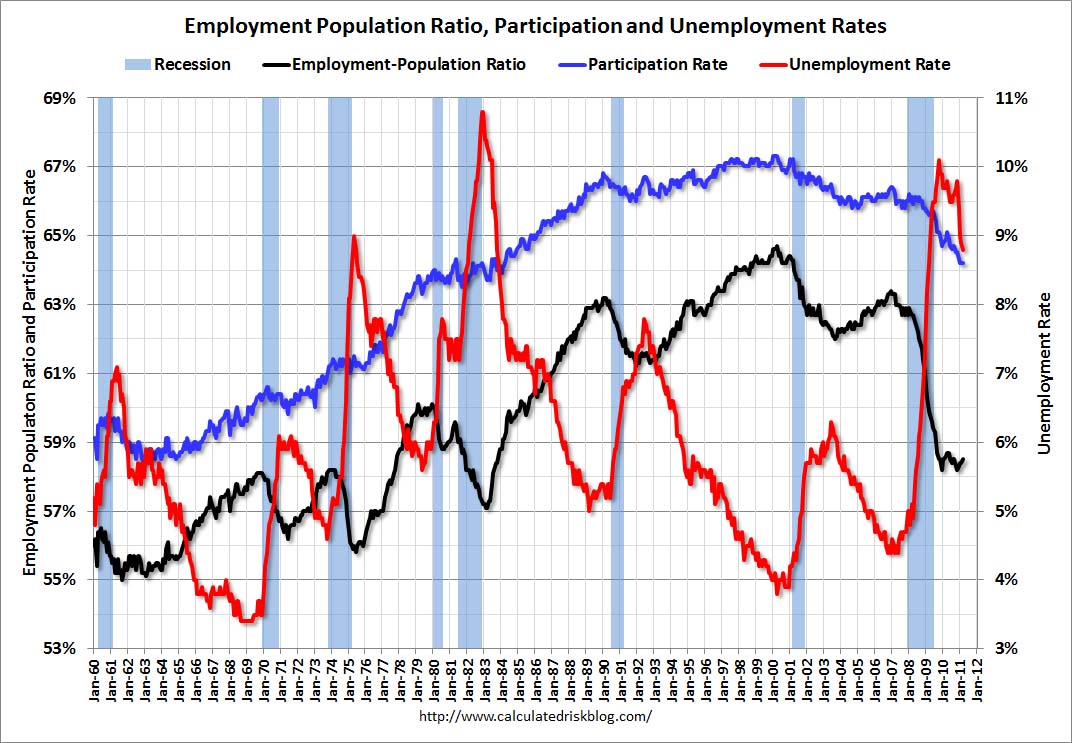

Moving on to employment, U.S unemployment currently stands at 8.8%. This number has been trending lower the past several months with much of the change coming from decreases in the labor participation rate. As depicted by below, the participation rate now sits just above 64% while the employment-population ratio has been fluctuating between 58-59%. Levels this low were last seen in 1983, when the U.S. was recovering from a double-dip recession and the high inflation of the 1970's. Historically, these statistics began trending upward shortly after the recession ended, however nearly two years into the current recovery the statistics are still trending downward. The first quarter of 2010 has seen job growth average nearly 200,000 jobs per month. Even maintaining that pace, it will take the U.S. at least 3 more years to simply recover all the jobs lost during the previous downturn (not including population growth). As a nation we may be becoming more used to high unemployment, however the current situation is far from normal.

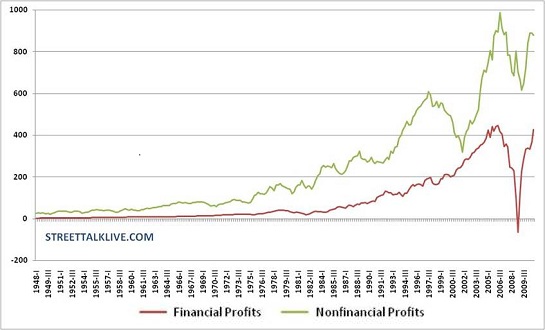

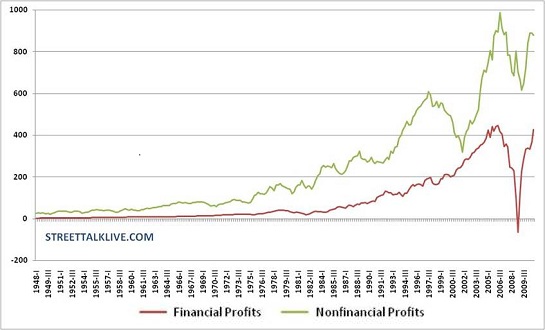

Stock markets in the U.S. have been on a tear since bottoming in March of 2009, rising nearly 100% within 2 years. The gains have largely been supported by rapidly increasing corporate profits (as seen below).

What’s striking about this data is that non-financial profits appear to be topping below their previous peak while financial profits, in the most recent data, have eclipsed previous all-time highs. Many pundits tout soaring financial profits as proof of TARP's success, effects of monetary policy, or simply intelligent bankers. However, considering effects of a ruling by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) may prove insightful. In early 2009, the FASB updated rule FAS 157, removing mark-to-market requirements for assets where the market is either unsteady or inactive. By removing this requirement, financial firms could revalue large percentages of their assets based on internal valuation models. Many assets types previously facing significant markdowns are lingering in unsteady or inactive markets. Financial firms are likely still holding trillions in assets currently priced based on individual models, including signficant quantities of residential and commercial real estate related assets. As the following chart shows, the value of real estate has moved sideways during the past two years and may be entering a double-dip.

What are the true values of the real estate assets held by financial firms and how does that affect profits? From a purely psycological/capitalist standpoint, we should expect internal values to exceed current market values. Prior to the financial crisis, financial firms had not considered any possibility of real estate values falling nationwide. As the black swan occurres, small percentage declines quickly resulted in cascading losses for many of the firms. Considering the number of mortgages currently underwater and delinquent, it’s unlikely the value of real estate assets has changed much since the relaxation of mark-to-market accounting. This fact has not prevented financial firms from boosting recent profits by reducing loan less reserves or even paying dividends using “excess” capital. Financial firms are even fighting desperately to have capital requirements lowered from the currently proposed 7%.

Why does all this matter? Let’s assume for a moment that the largest financial firms currently hold on average 5% in Tier 1, equity capital. Half of these firms’ assets are also tied up in either unsteady or inactive markets. If these firms were forced to show even a mere 10% loss on their illiquid assets, the losses would wipe out the entire equity base and render the firms insolvent. Back to the real world, some of the largest financial firms likely hold far higher percentages of illiquid assets, currently would be showing much larger than 10% mark-to-market losses, or both. This situation has led some to call many of our current financial firms, “zombies.”

Large federal deficits, extremely accomodative monetary policy, high unemployment and “zombie” banks are clearly not the hallamrk of a typical U.S. recovery. Weakness in state and local budgets, potential for a government shutdown and growing income inequality display further strain below the surface. Looking abroad, revolutions in the Middle East, sovereign debt crises in Europe and the tragic earthquake/tsunami/nuclear effects on Japan are from typical as well. Globally, the political and economic goal appears to be a game of "extend and pretend." While these sherades can continue, potentially for years, the losses will ultimately be recognized.

So is the current recovery/situation in the U.S. “normal”? The answer is most obviously no. A better question is would we want it to be normal? President Obama surged to victory only a few years ago using a campaign based on “change.” Since then, the Republicans have gotten on the bandwagon of representating “change.” Economic recoveries during the past 20 years have been largely jobless. Income disparity in our country has been growing for over 30 years with median real incomes barely budging. Government approval ratings are jokingly low. Maybe it is finally time the U.S. shuns “normal” and seeks change for the better. Making that bold leap requires accepting the current challenges still facing our economy, so that we can comprehensively and accurately address the underlying problems. Only once we accept our current situation and strive for change will the U.S. begin moving again towards displaying its full potential.

Coming Soon: As part of my search for more comprehensive knowledge of economics, I’ve nearly finished reading John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Needless to say, this brilliant text has provided significant ideas for future pieces and I was especially intrigued by his discussion of financial markets. Some future posts on this topic will be coming soon!