Following the ECB’s decision in July to stop paying interest-on reserves (IOER), many economic pundits have been and continue to pressure the Fed to pursue a similar action in hopes it will revive bank lending. At that time, I was highly suspicious of these arguments are countered that Making IOER Negative Equates to Raising Taxes And Raises Potential Of New Recession. My reasoning was, in part, based on the view that banks cannot lend out reserves and the total amount of reserves in this system is largely determined by the Fed’s open market operations.

In this post, we use the structure of the Fed’s balance sheet to illustrate why lowering the interest rate paid on reserve balances to zero would have no meaningful effect on the quantity of balances that banks hold on deposit at the Fed.

For our discussion, here is the section that really stands out:

The View from the Balance Sheet

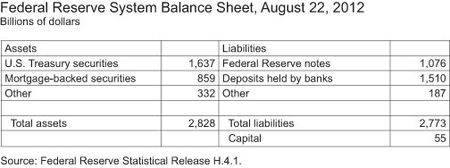

It’s important to keep in mind, however, what determines the total quantity of these balances. One way of understanding the issue is by looking at the Fed’s balance sheet, a simple version of which is presented in the table below.

As the table shows, the balances that banks hold on deposit at the Fed are liabilities of the Federal Reserve System. The other significant liability is currency in the form of Federal Reserve notes. Together, this currency and these deposits make up the monetary base, the most basic measure of the money supply in the economy. The composition of the monetary base between these two elements is determined largely by the amount of currency used by firms and households (both in the United States and abroad) to make transactions and by banks to stock their ATM networks.

What determines the size of the monetary base? As with any other institution’s balance sheet, the Fed’s dictates that its liabilities (plus capital) equal its assets. The Fed’s assets are predominantly Treasury and mortgage-backed securities, most of which have been acquired as part of the large-scale asset purchase programs. In other words, the size of the monetary base is determined by the amount of assets held by the Fed, which is decided by the Federal Open Market Committee as part of its monetary policy.

It’s now becoming clear where our story’s going. Because lowering the interest rate paid on reserves wouldn’t change the quantity of assets held by the Fed, it must not change the total size of the monetary base either. Moreover, lowering this interest rate to zero (or even slightly below zero) is unlikely to induce banks, firms, or households to start holding large quantities of currency. It follows, therefore, that lowering the interest rate paid on excess reserves will not have any meaningful effect on the quantity of balances banks hold on deposit at the Fed.

Reviewing the Fed’s balance sheet clearly illustrates that open market operations and large-scale asset purchases (QE) are no more than an asset swap with private banks in which the amount of reserves in the system expands. Banks cannot lend these reserves to the public and can only dispose of them through changes to the Fed’s balance sheet. Therefore, any hope that lowering or ending IOER will stimulate private credit creation can only come from a change in demand based on lower interest rates or revised expectations about future rates and asset prices.

Needless to say, I agree with the Fed that altering policy in this manner will have a negligible effect in spurring demand for loans. On the cost side, this policy presents uncertainty for the continued functioning of money market funds and reduces bank capital. Further, when the Fed eventually wishes to raise rates, IOER permits altering the Fed Funds rate without targeting the amount of reserves in the system. This NY Fed post appears to send a clear message that an "Interest-On-Reserves Regime" Will Rule Monetary Policy For The Foreseeable Future.