Households and businesses “with access to cheap borrowing” have been pouring money into stock, bond, housing and commodity markets rather than investing in tangible capital. The remarkable rise in asset prices has unfortunately not funneled down to households in the bottom four quintiles of income and wealth, only furthering the inequality gap.Cullen Roche addressed a similar issue yesterday in a post on The Fed’s Disequilibrium Effect via Nominal Wealth Targets:

Fed policy and the monetarist perspective on much of this can be highly destabilizing by creating this sort of ponzi effect where asset prices don’t always reflect the fundamentals of the underlying corporations. It’s not a coincidence that we’ve have 30 years of this sort of policy and also experienced the two largest nominal wealth bubbles in American history during this period.The title of this blog is also not a coincidence, since my formative years encompassed both the dot-com and housing bubbles. My relatively limited experience with financial markets and macroeconomics (based on age) has been punctuated by financial instability. These memories are the driving factor behind my desire to study financial instability and inform policy decisions that can stabilize the business cycle.

In a recent post on The Spinning Top Economy, Matthew Berg helps further my goal with insight on measuring financial instability (my emphasis):

Now we have Government IOUs on the bottom, serving as the base of the economy. Bank and Non-Bank IOUs are leveraged on top of those IOUs – somewhat precariously.

In fact, you can think of the economy as a spinning top rather than a pyramid. Like a spinning top, the more top-heavy the economy becomes, the greater its tendency to instability, and the more readily it will topple over and collapse in a financial crisis.

Now, what happens if, as was the case during the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble, private sector net financial assets go negative but net worth continues to grow?

In fact, the difference between the measures of net financial assets and net worth provides us with a good rule of thumb for how to spot a bubble economy. If private sector net worth is growing at a greater rate than private sector net financial assets are growing, then that means that the economy – symbolized by our spinning top – is growing more top-heavy.

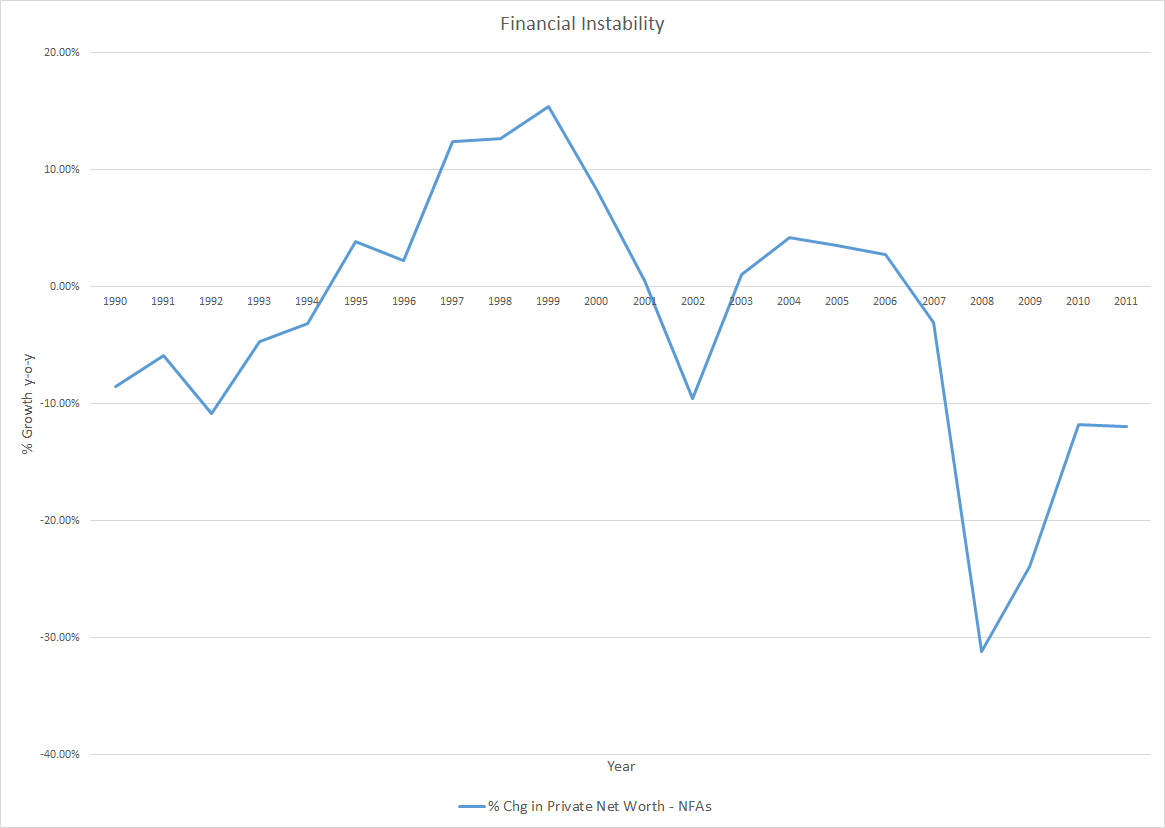

So, what happens if we make the spinning top more top-heavy? You can go ask your nearest Kindergartener – it becomes more likely to topple over.Since Matthew provides the guidelines for spotting “a bubble economy,” let’s take a look at the empirical data to see how well it aligns with the story. The first chart displays the growth rates of private sector net financial assets (NFAs) and private net worth over the past 20 years*:

The negative growth rate in private NFAs corresponds with the Clinton surpluses, while the two positive surges are due to the Bush tax cuts and Bush/Obama stimulus measures. Turning to the growth in private net worth, the brief decline stems from the bursting dot-com bubble and the massive drop from cratering house prices. Combining the two measures will show when/if the economy was becoming “top-heavy” (first chart displays the past 50 years; second chart is the same data but only the past 20 years, for clarity):

Past 50 Years

Past 20 Years

Growth of private net worth began outpacing the growth of private NFAs in 1995 for the first time since 1979. The difference in growth rates then remained positive for 10 of the next 11 years. This streak is truly remarkable given that prior to 1995, the difference had only been positive in five other years dating back to 1961.** At the end of 2006, the U.S. economy was clearly more “top-heavy” than any previous time in the post-war era.Over the past three decades, growth in private debt exceeding income and declining nominal interest rates have generated enormous returns for asset holders. Throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s, federal deficits provided more than enough NFAs to keep pace with rising private net worth. Then, in 1995, deficits began decreasing just as the growth of net worth (and private debt-to-GDP) began accelerating higher. The unsurprising result has been more than a decade of meager asset returns, subpar economic growth and high unemployment.

The government policy of targeting nominal wealth, driven by an expansion of private debt, has failed not only at increasing net worth but also, and more importantly, at creating sustainable growth in output and employment. Going forward the focus of policy must return to promoting the growth of income and assets, which in turn will fuel higher output, employment and ultimately wealth.

*Data for private net worth comes from the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States (Z.1). Data for private net financial assets (NFAs) comes from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) at the BEA.

**Aside from 1979, growth of private net worth exceeded the growth of private NFAs in 1961, 1965, 1969 and 1978 (0.05%).

Related posts:

The Rise of Debt, Interest, and Inequality

Fear of Bubbles, Not Inflation, Returns to the Fed

Why the Federal Reserve Mandate Means That Bernanke Doesn't Have to Worry About Bubbles

Regarding inequality, I have a theory (that I haven't been able to empirically verify yet) that after the 1970s, with the rise of new financial assets and new lending channels, the movement of corporate investment into these assets (and the consequent self-perpetuating bubble) sacrificed investment into workers' productivity, holding back their wages. I haven't looked at the data sector by sector, but some of it suggests my hunch isn't true (there was a productivity boom in the 90s, and nominal wages have grown).

ReplyDeleteThat's an interesting theory definitely worth considering. A slightly different take would be that the rise in corporate borrowing generated new and frequently rising costs for businesses. Higher prices would therefore have reflected a higher cost of production due to borrowing rather than wages. Similarly, increases in revenue/profits may have been used to pay back some of the debt rather than increase wages. From this perspective the extra cash flows of business were paid to debt holders instead of workers, with the former representing wealthier households and the latter the less well off.

DeleteI tend to be somewhat wary of using analogies like a "spinning top" to draw conclusions about the economy. Just because a spinning top topples if it is too top-heavy, doesn't necessarily mean the same is true about an economy. Berg also says "It’s like a game of musical chairs. When the music stops, there are not enough chairs (net financial assets) to go around." Again, I'm not sure that trying to use such an analogy is totally wise. But the idea behind it is interesting. Why is it, though, that government IOUs are the "stable base" on which everything else rests?

ReplyDeleteWhat does your last graph look like in levels instead of percent changes? Does it show that we now have a highly stable financial system? What would your financial instability measure look like for other countries? Especially smaller countries with less "privileged" currency than the dollar?

I'm having trouble thinking of what the policy implications would be, if this were the measure of financial stability we wanted to target. Fiscal deficits? Countries can't all do that at once. There's the capital account part of Berg's first graph that makes things tricky...

My blog post today is somewhat related to your first few paragraphs: http://carolabinder.blogspot.com/2013/03/bernanke-bankers-bubbles.html

The non-govt sector entails a budget constraint that is not present for govt's with fiat, floating currencies. The non-govt sector can't create net financial assets itself since each asset is obviously someone's asset and someone's liability. The primary difference in my mind relates to risk. A private sector liability/asset holds varying risk of default and interest payments are merely a transfer between private actors. A govt liability (private NFA) lacks the default risk and the interest income provides additional spending power to the private sector. For those reasons government IOUs are the "stable base", although they are not without any risk.

DeleteI've been studying for midterms the past week and haven't had a chance to create the graphs you recommended, but plan on doing so in the near future. Thanks for the suggestions.

The policy implications of this are certainly difficult. Obviously trying to prevent rising net worth seems a bit silly although there are many ways in which the govt/CB could be less supportive of asset bubbles. In this case I'm thinking primarily of changes to tax and regulatory policies. On the fiscal side, larger deficits would seem like the answer but those could easily exacerbate a speculative bubble. Therefore I think the focus would have to be on the net worth side.

The Fed printed too much money and held interest rates too low, too long prior to 2009, blowing up an economic bubble. I do believe that extra cash flows of business were paid to debt holders instead of workers, and the latter experienced sensitive worsening of life conditions and they continue now. For a lot of people to apply for extra cash online is the only way out to keep afloat.

ReplyDeleteNice..

ReplyDeleteThese sneeze guard posts have good options like flange canopy covers, LED lighting, support post, end panels. It’s stand-upon fixed with a base flange.

Great Article which capture important information Thanks For sharing you can also click my QuickBooks Service at

ReplyDeleteQuickBooks Customer Service