Lord Keynes, at Social Democracy for the 21st Century, provides data on Japanese Real GDP Growth from 1925–2001 and notes the following:

In the 1980s, Japan engaged in ill-conceived financial deregulation (Fukao 2003: 134–135), which was one major cause of the asset bubble in these years (although poorly designed tax policies and monetary policy were clearly involved too). The collapse of the asset bubble and the balance sheet recession (a form of debt deflationary crisis) caused the “lost decade.”

From the data above, we can see that the “lost decade” was really an era of low growth, not continuous negative growth. Japan was not in recession from 1993–1997, but had serious deleveraging problems, a banking crisis, and debt deflation.

Many myths have arisen about the lost decade, and one of them is that Keynesianism somehow “failed” to work in this era. That is nonsense. If anything, Keynesianism saved Japan from a terrible depression. In fact, when fiscal stimulus was abandoned for austerity in 1997, the economy plunged into a recession in 1998.

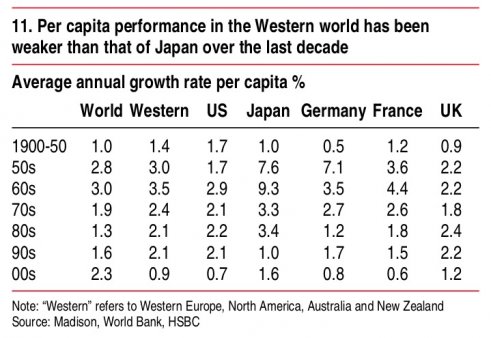

Of the myths regarding Japan’s lost decade (now decades), I’ll admit to having been unaware that 1998 marked the first year of negative real GDP growth since 1974 (and only second since 1945!). Since then, Japan has unsuccessfully tried to get on a fiscally sustainable path (whatever that means) as more frequent recessions have led to larger budget deficits (and growing debt/GDP) that merely prevent larger economic declines. Despite the persistence of misguided fiscal (and monetary) policy, Japan’s per capita economic growth has remained on par with the Western world.

With nonfinancial private sector balance sheets largely repaired, Japan appears poised to continue leading the Western world if government policies improve. Unfortunately last night’s Joint Statement of the Government and the Bank of Japan on Overcoming Deflation and Achieving Sustainable Economic Growth shows the lessons of a previous age remain forgotten.

Mitt Romney’s selection of Paul Ryan as the Republican Vice Presidential candidate ensures that a major focus of the upcoming election will be the federal budget. Many voters appear concerned that continued deficits and an increasing debt-to-GDP ratio will lead to some combination of higher interest rates, slower growth, (hyper) inflation and/or default. In a debate that was already destined to center around this mainstream view of fiscal sustainability, the selection of Ryan will only further cement incorrect theories within public knowledge.

Over the past couple years I have attempted to help further an opposing view of the federal budget, one based on theories of modern money.* Recently I stumbled upon a 2006 paper by Scott Fullwiler, titled Interest Rates and Fiscal Sustainability, which offers a surprisingly complete explanation of a modern money regime. Presenting the major departures from mainstream views, Fullwiler concludes:

“in a modern money regime such as the U. S., deficits do not crowd out but rather create net financial assets for the non-government sector, the operational purpose of bond sales is interest-rate support, and the Fed’s interest rate target anchors other short-term rates given that tax liabilities must be paid in reserve balances. As a result of these regime characteristics, the interest rate on the national debt is a monetary phenomenon that primarily reflects the current (and expected, if long-term, fixed-rate time deposits are issued) interest-rate “anchor” set by the Fed, not the size of the current or expected future levels of the debt or deficits as assumed in the loanable fund market paradigm. This monetary nature of interest on the national debt is indisputable when one considers that the federal government never needs to issue its debt as time deposits and could simply create (assuming a positive interest rate target) interest-bearing reserve balances that earn interest at the Fed’s target interest rate, as in the proposals discussed earlier. Self-imposed constraints, including legal restrictions on operating procedures or lack of political will, might keep a simplified procedure such as this from being implemented, but they do not change the monetary nature of rates paid on the national debt; the choice to issue short-term or long-term securities (i.e., non-government sector time deposits at the Fed) is simply a more complicated version of this more general or (in the case of a zero interest rate target) “natural” case. (p.26)”

For readers interested in fiscal and/or monetary policy, Fullwiler’s paper is a fantastic resource. Over the coming days it is my intention to offer a more detailed examination of the various principles outlined above with further excerpts from the paper and real-world applications. Even if the basic principles of a modern monetary system supplants current mainstream theories, clear cut policy choices will remain out of reach. The policy conversations, however, will improve dramatically and the likelihood of better outcomes will increase significantly.

* I mention theories of modern money rather than Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) to include support for Monetary Realism, Post-Keynesians, Circuitistes, Horizontalists and others that accept the basic principles laid out by Fullwiler.