1) Spain requests access to ECB’s OMT - Since ECB President Mario Draghi announced the OMT program, yields on Spanish debt have fallen rather dramatically. Although this eases financing pressure, it has done little to alter the actual economy’s downward spiral. During 2012 Spain’s GDP growth became increasingly negative, falling by 1.8% year-on-year in the fourth quarter. Meanwhile unemployment continues its meteoric rise to over 26% for the general population and nearly 60% for youth. With the large banks still severely undercapitalized and households over-indebted, private sector lending continues to decline:

Seeing no recovery and potentially a worsening decline, “bond vigilantes” will eventually test Draghi’s threat. At that point Spain will be forced to accept a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in return for ECB bond-buying through the OMT program.

2) The Euro finishes the year above $1.30 - After falling nearly 10% during the first half of 2012, the euro has more than recouped its losses on the back of optimism and deflationary policies.

At points during 2013 the optimism is likely to fade, but I expect politicians and central bankers will take the necessary steps to quell fears for the time being. Unfortunately those steps will involve further deflationary policies that push the euro higher. These competing forces will largely cancel out, leaving the euro close to or above where it began the year.

3) The Eurozone remains in recession the entire year - Forecasters now expect euro-zone economic activity to be flat this year, down from a previous prediction of 0.3% growth made just three months ago. Last year saw practically continuous downgrades to GDP growth forecasts and I expect this year to be no different. Austerity measures are momentarily easing, but more will likely be enacted based on the outcomes of several elections. The recent appreciation of the euro against several major currencies will also dampen growth by putting pressure on net exports. With banks across Europe trying to build up capital and persistently high unemployment, the private sector will remain especially weak. Though Germany may experience a temporary rebound, the Eurozone as a whole will not register GDP growth this year.

4) The Japanese yen rises above 90 per $ - Since the election of PM Shinzo Abe, the yen has fallen fast and is down more than 20% from recent highs.

During this time the Nikkei has risen more than 20%, yet yields on Japanese sovereign debt are little changed. This suggests many foreigners may be speculating on the supposedly forthcoming monetary and fiscal stimulus. As previously stated, the fiscal stimulus will probably be small and short-term. On the monetary front, short of actually entering the foreign exchange market, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has essentially no mechanism to spur inflation and thereby cause a sustained depreciation of the yen. When market participants recognize the inability of Japan to avoid continued deflation, the yen will return to appreciating against the dollar.

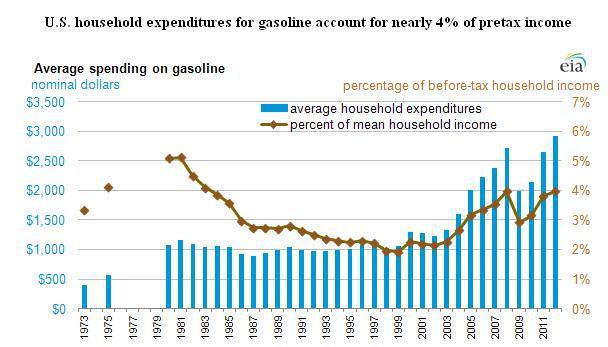

5) Gas prices will peak above $4.20 per gallon and set a new yearly record-high average above $3.75 per gallon - Gasoline prices have been on the rise for the past 31 days, currently averaging approximately $3.75 per gallon. Though this current streak will probably end soon, prices are unlikely to give back much of the gains before beginning the typical rise into summer. The ongoing potential for flare ups in the Middle East will keep prices elevated throughout the year. Higher gas prices, which already account for 4% of before-tax household income (chart below), will be a drag on consumer spending in 2013.

6) U.S. Yearly GDP growth falls below 1.5% - Forecasts of ~3% annual GDP growth over the past couple years have been overly optimistic as real growth in 2011 and 2012 was merely 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively. Apparently forecasters are being a bit tamer in their estimates this year, now expecting only 2% annual growth. Unfortunately I suspect these estimates will once again prove too optimistic. Various tax hikes and the upcoming sequester (which will go through in some respect) will reduce the budget deficit by a few percent this year. Housing is likely to remain a bright spot, but further declines in interest rates will not lead to similar magnitudes of the wealth effect. Credit remains tight for many households and small business, which should also limit private sector activity. All of these factors combined will probably not be enough to bring about a new recession but will lead to the lowest annual growth rate during this upswing.

7) U.S. Unemployment rises above 8% - Currently sitting at 7.9%, the unemployment rate is forecast to decline during 2013. Due to weaker GDP growth, corporate revenues will barely rise again this year. As companies face increasing pressure to maintain profit margins at record levels, a new wave of layoffs may occur. Separately, continuing economic growth will encourage previously discouraged workers to re-enter the job market. Both of these factors will lead to slightly higher measured unemployment.

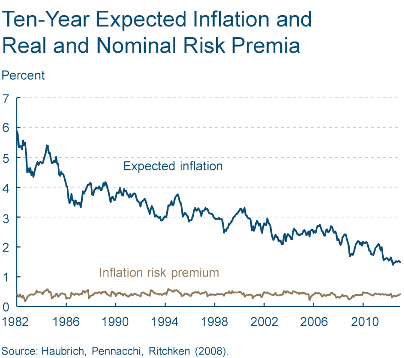

8) Federal Reserve forecasts shift first rate hike to 2016 - After extending their forecast for the first rate hike to 2015, the Federal Reserve changed its tactics to a more rule-based monetary policy. The Fed has, in effect, promised to keep rates low until we've hit either 6.5 percent unemployment or 2.5 percent inflation. Based on the above outlook for unemployment and a continuing decline in inflation expectations (chart below), FOMC members will revise their own forecasts and push back expectations for the first rate hike.

9) U.S. Corporate Earnings (ex-Federal Reserve) finish year below 2012 peak - Meager revenue growth was not enough to prevent U.S. Corporate Profits after tax from reaching record highs in the fourth quarter of 2012 on the back of record profit margins.

As global growth slows in 2013, revenues will come under further pressure. At this point the ability of firms to continue cutting costs without sacrificing output seems limited, which means margins may begin to compress. As margins revert to previous norms, earnings will register a yearly decline.

10) Bonds outperform stocks - During the first seven weeks of this year the stock market has been on fire, even though earnings estimates continue to fall.

Multiple expansion is currently being driven by the Federal Reserve’s actions despite their ineffectiveness at generating actual NGDP growth. When investors eventually turn their attention to continuing troubles in Europe, ongoing deflation in Japan, and/or weakening growth in China, U.S. earnings may once again enter the picture. Recognition that S&P 500 earnings growth has slowed substantially may cause the market to give up much of this year’s gain. These concerns combined with declining inflation expectations will result in many investors returning to the safety of U.S. Treasuries. The subsequent rise in prices (decline in rates) will generate another year of positive returns for the Treasury market.

Will my predictions prove too pessimistic once again? Only time will tell...

2) The Euro finishes the year above $1.30 - After falling nearly 10% during the first half of 2012, the euro has more than recouped its losses on the back of optimism and deflationary policies.

At points during 2013 the optimism is likely to fade, but I expect politicians and central bankers will take the necessary steps to quell fears for the time being. Unfortunately those steps will involve further deflationary policies that push the euro higher. These competing forces will largely cancel out, leaving the euro close to or above where it began the year.

3) The Eurozone remains in recession the entire year - Forecasters now expect euro-zone economic activity to be flat this year, down from a previous prediction of 0.3% growth made just three months ago. Last year saw practically continuous downgrades to GDP growth forecasts and I expect this year to be no different. Austerity measures are momentarily easing, but more will likely be enacted based on the outcomes of several elections. The recent appreciation of the euro against several major currencies will also dampen growth by putting pressure on net exports. With banks across Europe trying to build up capital and persistently high unemployment, the private sector will remain especially weak. Though Germany may experience a temporary rebound, the Eurozone as a whole will not register GDP growth this year.

4) The Japanese yen rises above 90 per $ - Since the election of PM Shinzo Abe, the yen has fallen fast and is down more than 20% from recent highs.

During this time the Nikkei has risen more than 20%, yet yields on Japanese sovereign debt are little changed. This suggests many foreigners may be speculating on the supposedly forthcoming monetary and fiscal stimulus. As previously stated, the fiscal stimulus will probably be small and short-term. On the monetary front, short of actually entering the foreign exchange market, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has essentially no mechanism to spur inflation and thereby cause a sustained depreciation of the yen. When market participants recognize the inability of Japan to avoid continued deflation, the yen will return to appreciating against the dollar.

5) Gas prices will peak above $4.20 per gallon and set a new yearly record-high average above $3.75 per gallon - Gasoline prices have been on the rise for the past 31 days, currently averaging approximately $3.75 per gallon. Though this current streak will probably end soon, prices are unlikely to give back much of the gains before beginning the typical rise into summer. The ongoing potential for flare ups in the Middle East will keep prices elevated throughout the year. Higher gas prices, which already account for 4% of before-tax household income (chart below), will be a drag on consumer spending in 2013.

6) U.S. Yearly GDP growth falls below 1.5% - Forecasts of ~3% annual GDP growth over the past couple years have been overly optimistic as real growth in 2011 and 2012 was merely 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively. Apparently forecasters are being a bit tamer in their estimates this year, now expecting only 2% annual growth. Unfortunately I suspect these estimates will once again prove too optimistic. Various tax hikes and the upcoming sequester (which will go through in some respect) will reduce the budget deficit by a few percent this year. Housing is likely to remain a bright spot, but further declines in interest rates will not lead to similar magnitudes of the wealth effect. Credit remains tight for many households and small business, which should also limit private sector activity. All of these factors combined will probably not be enough to bring about a new recession but will lead to the lowest annual growth rate during this upswing.

7) U.S. Unemployment rises above 8% - Currently sitting at 7.9%, the unemployment rate is forecast to decline during 2013. Due to weaker GDP growth, corporate revenues will barely rise again this year. As companies face increasing pressure to maintain profit margins at record levels, a new wave of layoffs may occur. Separately, continuing economic growth will encourage previously discouraged workers to re-enter the job market. Both of these factors will lead to slightly higher measured unemployment.

8) Federal Reserve forecasts shift first rate hike to 2016 - After extending their forecast for the first rate hike to 2015, the Federal Reserve changed its tactics to a more rule-based monetary policy. The Fed has, in effect, promised to keep rates low until we've hit either 6.5 percent unemployment or 2.5 percent inflation. Based on the above outlook for unemployment and a continuing decline in inflation expectations (chart below), FOMC members will revise their own forecasts and push back expectations for the first rate hike.

9) U.S. Corporate Earnings (ex-Federal Reserve) finish year below 2012 peak - Meager revenue growth was not enough to prevent U.S. Corporate Profits after tax from reaching record highs in the fourth quarter of 2012 on the back of record profit margins.

As global growth slows in 2013, revenues will come under further pressure. At this point the ability of firms to continue cutting costs without sacrificing output seems limited, which means margins may begin to compress. As margins revert to previous norms, earnings will register a yearly decline.

10) Bonds outperform stocks - During the first seven weeks of this year the stock market has been on fire, even though earnings estimates continue to fall.

Multiple expansion is currently being driven by the Federal Reserve’s actions despite their ineffectiveness at generating actual NGDP growth. When investors eventually turn their attention to continuing troubles in Europe, ongoing deflation in Japan, and/or weakening growth in China, U.S. earnings may once again enter the picture. Recognition that S&P 500 earnings growth has slowed substantially may cause the market to give up much of this year’s gain. These concerns combined with declining inflation expectations will result in many investors returning to the safety of U.S. Treasuries. The subsequent rise in prices (decline in rates) will generate another year of positive returns for the Treasury market.

Will my predictions prove too pessimistic once again? Only time will tell...