Over the past few years it has become increasingly clear that the Federal Reserve and federal government are targeting rising asset prices, rather than incomes, as a way of generating economic growth. A recent post outlined some of the dangers of persistent negative real interest rates:

Households and businesses “with access to cheap borrowing” have been pouring money into stock, bond, housing and commodity markets rather than investing in tangible capital. The remarkable rise in asset prices has unfortunately not funneled down to households in the bottom four quintiles of income and wealth, only furthering the inequality gap.

Cullen Roche addressed a similar issue yesterday in a post on The Fed’s Disequilibrium Effect via Nominal Wealth Targets:

Fed policy and the monetarist perspective on much of this can be highly destabilizing by creating this sort of ponzi effect where asset prices don’t always reflect the fundamentals of the underlying corporations. It’s not a coincidence that we’ve have 30 years of this sort of policy and also experienced the two largest nominal wealth bubbles in American history during this period.

The title of this blog is also not a coincidence, since my formative years encompassed both the dot-com and housing bubbles. My relatively limited experience with financial markets and macroeconomics (based on age) has been punctuated by financial instability. These memories are the driving factor behind my desire to study financial instability and inform policy decisions that can stabilize the business cycle.

In a recent post on The Spinning Top Economy, Matthew Berg helps further my goal with insight on measuring financial instability (my emphasis):

Now we have Government IOUs on the bottom, serving as the base of the economy. Bank and Non-Bank IOUs are leveraged on top of those IOUs – somewhat precariously.

In fact, you can think of the economy as a spinning top rather than a pyramid. Like a spinning top, the more top-heavy the economy becomes, the greater its tendency to instability, and the more readily it will topple over and collapse in a financial crisis.

Now, what happens if, as was the case during the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble, private sector net financial assets go negative but net worth continues to grow?

In fact, the difference between the measures of net financial assets and net worth provides us with a good rule of thumb for how to spot a bubble economy. If private sector net worth is growing at a greater rate than private sector net financial assets are growing, then that means that the economy – symbolized by our spinning top – is growing more top-heavy.

So, what happens if we make the spinning top more top-heavy? You can go ask your nearest Kindergartener – it becomes more likely to topple over.

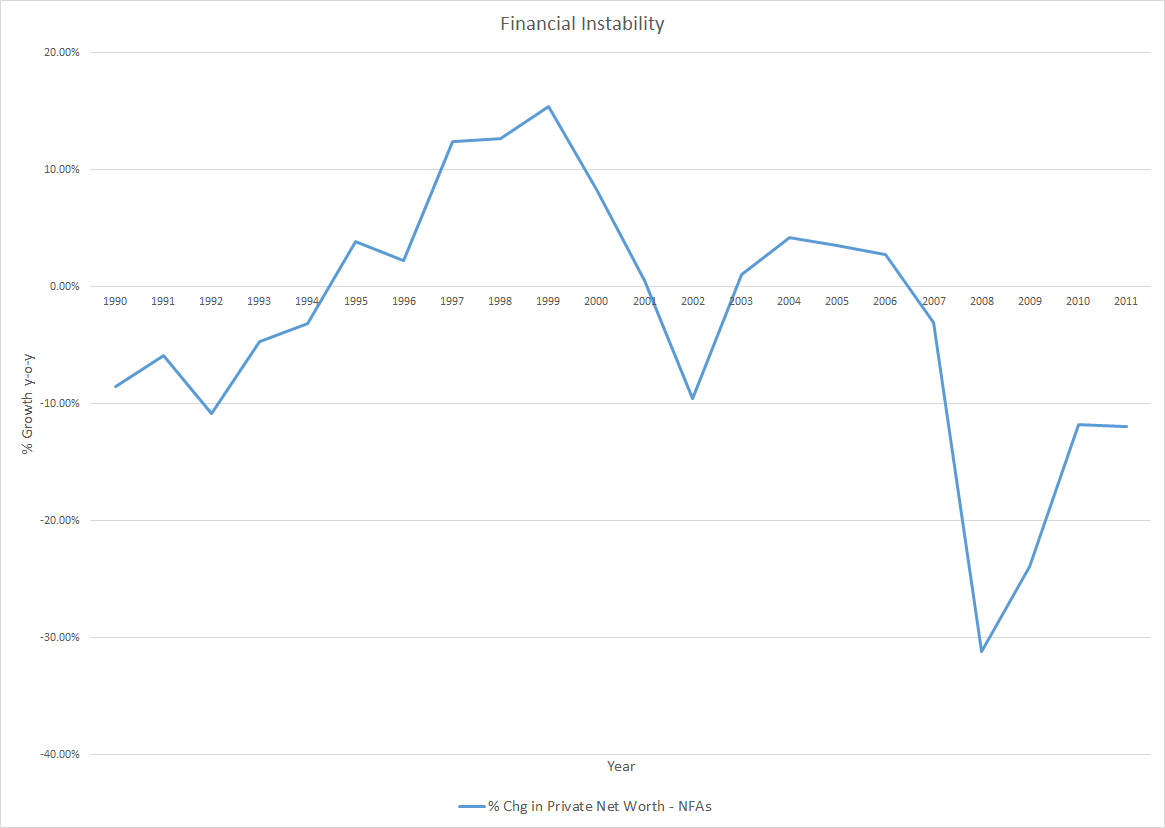

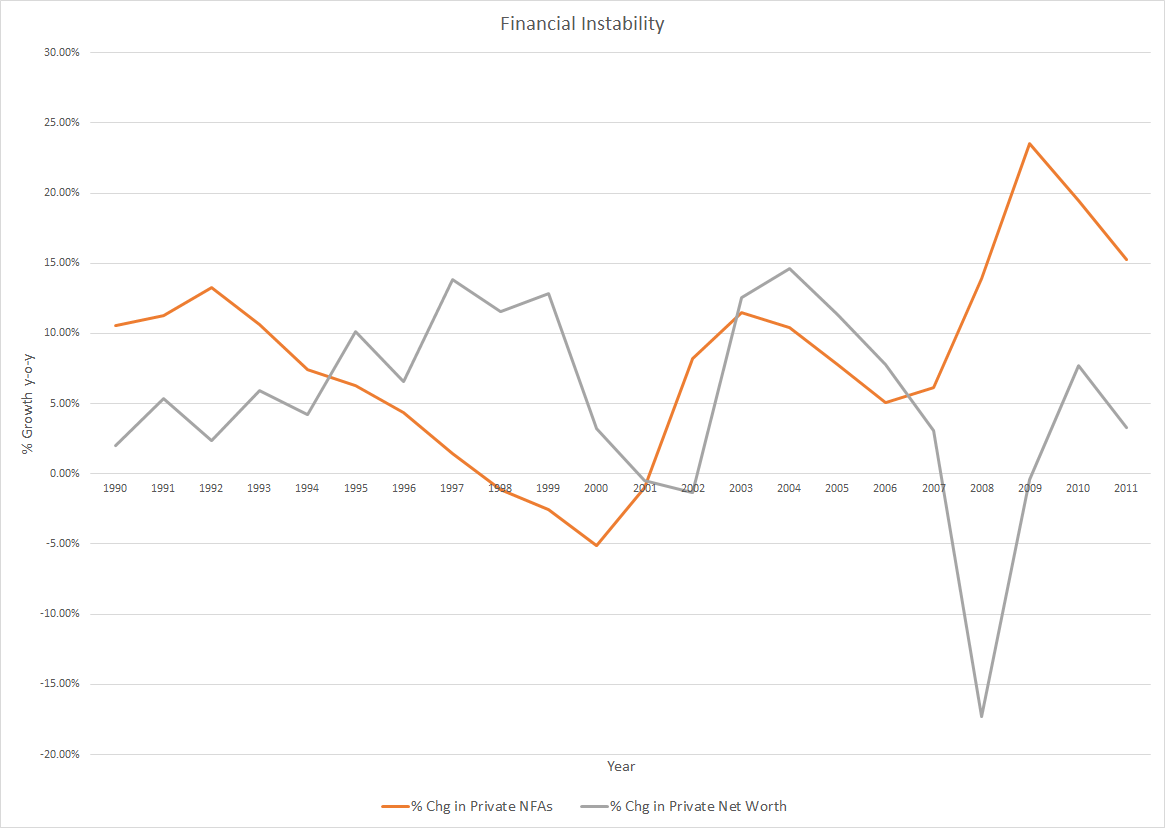

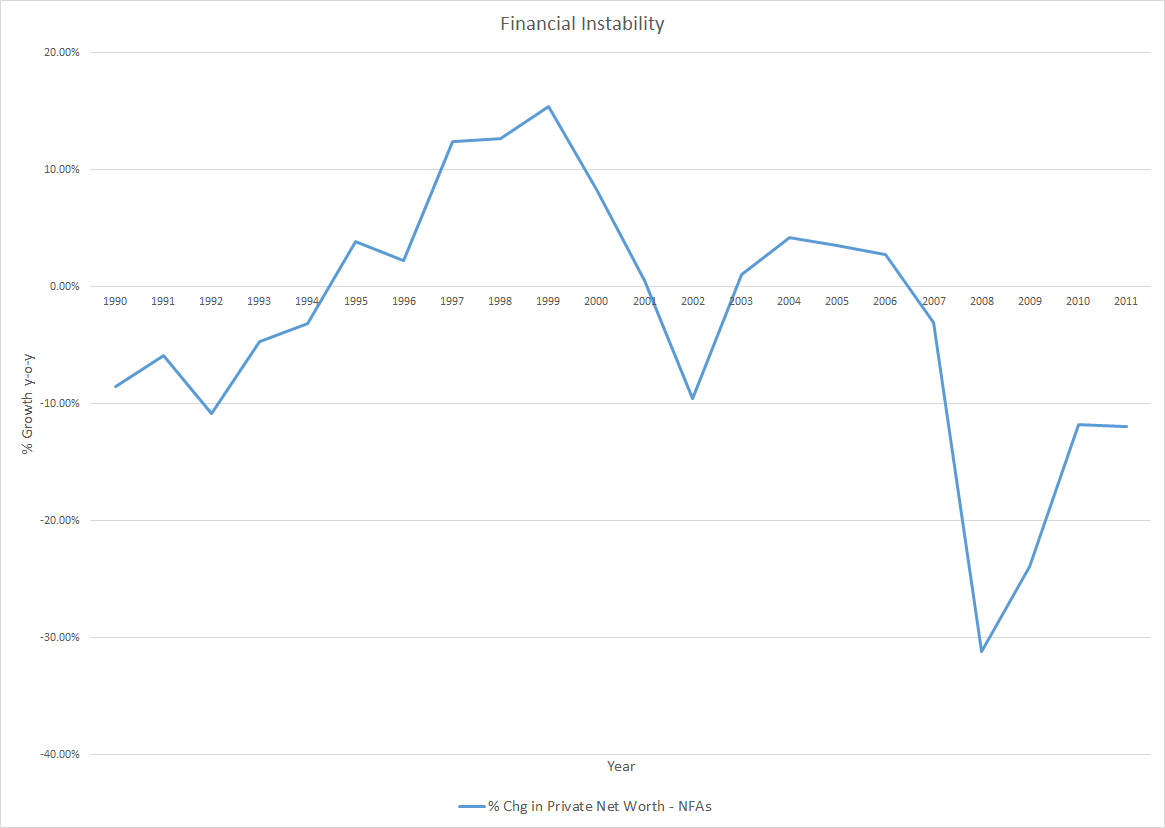

Since Matthew provides the guidelines for spotting “a bubble economy,” let’s take a look at the empirical data to see how well it aligns with the story. The first chart displays the growth rates of private sector net financial assets (NFAs) and private net worth over the past 20 years*:

The negative growth rate in private NFAs corresponds with the Clinton surpluses, while the two positive surges are due to the Bush tax cuts and Bush/Obama stimulus measures. Turning to the growth in private net worth, the brief decline stems from the bursting dot-com bubble and the massive drop from cratering house prices. Combining the two measures will show when/if the economy was becoming “top-heavy” (first chart displays the past 50 years; second chart is the same data but only the past 20 years, for clarity):

Past 50 Years

Past 20 Years

Growth of private net worth began outpacing the growth of private NFAs in 1995 for the first time since 1979. The difference in growth rates then remained positive for 10 of the next 11 years. This streak is truly remarkable given that prior to 1995, the difference had only been positive in five other years dating back to 1961.** At the end of 2006, the U.S. economy was clearly more “top-heavy” than any previous time in the post-war era.

Over the past three decades, growth in private debt exceeding income and declining nominal interest rates have generated enormous returns for asset holders. Throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s, federal deficits provided more than enough NFAs to keep pace with rising private net worth. Then, in 1995, deficits began decreasing just as the growth of net worth (and private debt-to-GDP) began accelerating higher. The unsurprising result has been more than a decade of meager asset returns, subpar economic growth and high unemployment.

The government policy of targeting nominal wealth, driven by an expansion of private debt, has failed not only at increasing net worth but also, and more importantly, at creating sustainable growth in output and employment. Going forward the focus of policy must return to promoting the growth of income and assets, which in turn will fuel higher output, employment and ultimately wealth.

*Data for private net worth comes from the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States (Z.1). Data for private net financial assets (NFAs) comes from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) at the BEA.

**Aside from 1979, growth of private net worth exceeded the growth of private NFAs in 1961, 1965, 1969 and 1978 (0.05%).

Related posts:

The Rise of Debt, Interest, and Inequality

Fear of Bubbles, Not Inflation, Returns to the Fed

Why the Federal Reserve Mandate Means That Bernanke Doesn't Have to Worry About Bubbles

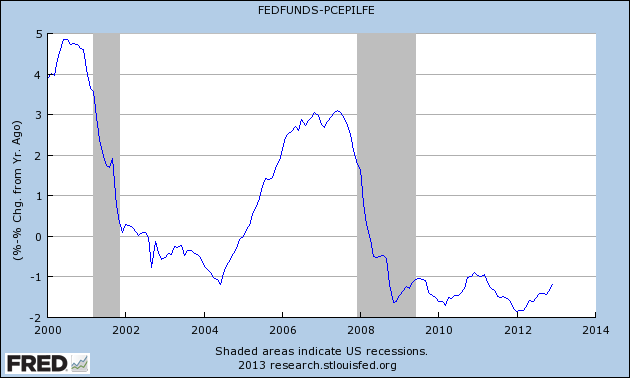

Earlier this week I discussed the dangers of misunderstanding “helicopter money” and higher inflation targets. A focus of that post was the incentives stemming from negative real interest rates that will lead to greater investment in real assets, not businesses. The obvious implication is that negative real interest rates entail significant risk of spurring asset bubbles.

This discussion of asset bubbles comes on the heels of St. Louis Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein’s speech that suggested the Fed was becoming increasingly concerned about bubbles, not inflation. According to a recent Bloomberg article, apparently Fed Chairman Bernanke was not onboard with the supposed shift (h/t Tim Duy):

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke minimized concerns that the central bank’s easy monetary policy has spawned economically-risky asset bubbles in comments at a meeting with dealers and investors this month, according to three people with knowledge of the discussions.

Do Bernanke’s comments imply the change Stein alluded to is not really happening? Not necessarily. To understand why, one must consider the goals assigned to Bernanke or any Fed Chairman for that matter. The following is from Chapter 2 of the Federal Reserve System’s own publication, Purposes & Functions:

The goals of monetary policy are spelled out in the Federal Reserve Act, which specifies that the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee should seek “to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

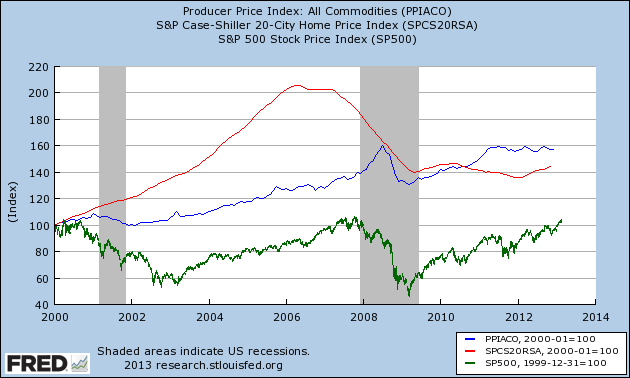

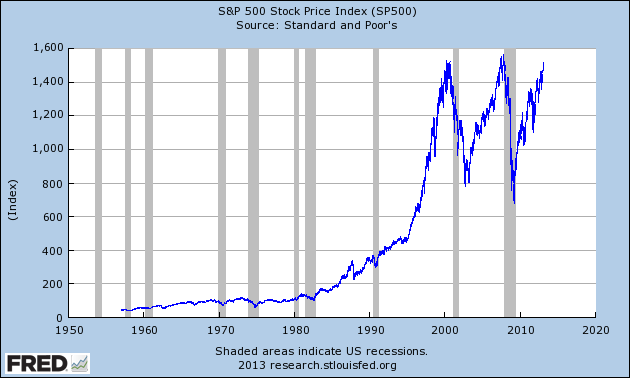

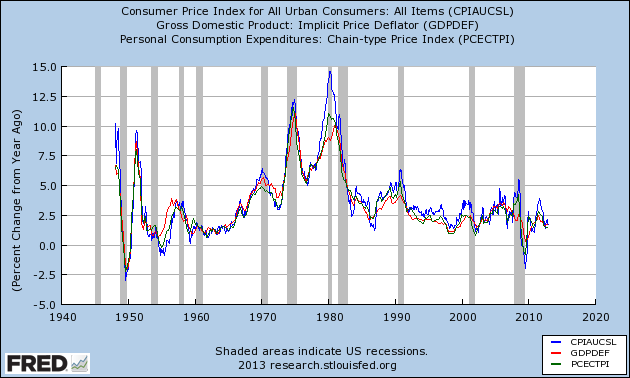

Although no explicit mention of preventing asset bubbles is made, the goal of stable prices leaves the door open for such an interpretation. Before addressing the Fed’s own interpretation of stable prices, its worth discussing the specific types of assets that are seemingly most prone to bubbles. The three major categories are commodities (e.g. oil, copper, sugar), financial assets (e.g. stocks and bonds), and housing. During the past decade real interest rates have actually been negative more often than not (Real Interest Rate = Effective Fed Funds rate - core PCE):

Unsurprisingly the past decade has also witnessed asset bubbles in commodities, stocks and housing:

Prices of these assets have clearly been anything but stable. So has the Fed failed in that aspect of its mandate? The answer is a resounding “NO.”

To remedy the cognitive dissonance readers may be experiencing, consider how the aforementioned real assets affect the FOMC’s preferred inflation measure, core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). Financial assets are noteworthy in their distinct omission from the type of products making up PCE. Commodities are included in the general price measure, however core PCE is calculated by excluding a couple of the more volatile commodity components: food and energy. Housing is actually included in core PCE but is calculated using the space rent of nonfarm owner-occupied homes, not actual house prices. Focusing on core PCE thereby removes any direct concern with asset bubbles.

Bernanke has already announced his plans to step down as Fed Chairman early next year (2014). Given the Fed’s stated mandate and preferred measure of prices, it is no wonder that Bernanke is unconcerned with asset bubbles. The goals of his chair are to maximize employment and maintain stable prices. Since the types of assets prone to bubbling are not included in core PCE and appear relatively uncorrelated with that measure, to the degree that bubbles can benefit employment in the short run, they may actually be desirable.*

These institutional incentives of a Fed Chairman are unfortunately at odds with the country’s longer term economic goals. Asset bubbles created by excessive lending and/or negative real interest rates are always followed by busts. These busts are simply the recognition of malinvestment that already took place during the boom. If the booms are financed with significant leverage, the resulting deleveraging may lead to a debt deflationary spiral. Whether or not that’s the case, though it usually is, malinvestment suppresses both employment and economic growth over time.

One can argue over whether Bernanke’s views on the effectiveness of monetary policy are correct or not, but his decision to ignore asset bubbles is perfectly rational given the circumstances. Shifting the Fed’s focus from inflation to bubbles will therefore require changing the institutional incentives.

*The three major asset categories mentioned above presumably will have very different effects on employment. Among the three, commodity bubbles are least desirable from an employment perspective. Higher commodity prices generally hurt consumer spending, which may lead to a temporary decline in employment. Housing bubbles are the most desirable in these terms since the increased demand can generate a temporary employment boom in construction and housing-related services.

St. Louis Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein recently gave a speech titled "Overheating in Credit Markets: Origins, Measurement, and Policy Responses."

Carola Binder was struck by the historical relevance of the chosen terminology and offered the following comment in a post on Overheating and the Fed:

In the New York Times, Binyamin Applebaum writes that Stein's speech "underscored that the Fed increasingly regards bubbles, rather than inflation, as the most likely negative consequence of its efforts to reduce unemployment by stimulating growth." In fact, the Fed's concern about bubbles is not so new. After the Great Depression, it was widely believed that the stock market overheated in the 1920s, leading to the Great Crash in 1929 and the onset of the Depression. In those days, the word for bubbles or overheating was speculation, and it became a dirty word indeed. After the Great Depression, speculation remained a major concern of the Fed. The Fed very explicitly regarded bubbles as the most likely negative consequence of its efforts to reduce unemployment by stimulating growth.

Apparently the Fed has come full circle. Carola goes on to provide a couple excerpts from FOMC minutes during the 1950’s, the last time the Federal Reserve was concerned with asset bubbles instead of inflation. The subsequent change in thought is not overly surprising given that stock markets flatlined starting in the mid-1960’s, as inflation picked up and became a major cause for concern throughout the 1970’s. What is disturbing, is the Federal Reserve’s failure to recognize the changing landscape over the past three decades.

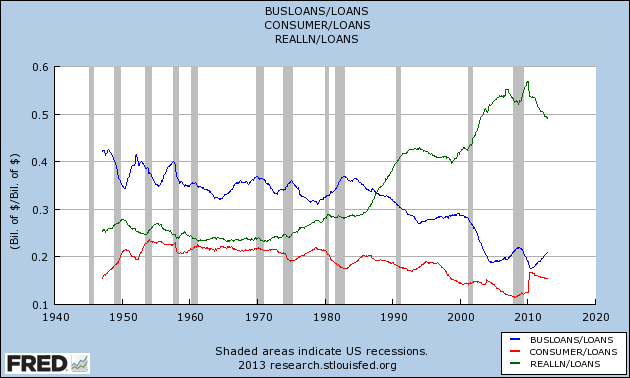

During that time, commercial bank lending has largely shifted its priorities from financing tangible (capital) investment through business loans to financing the purchase of already existing assets (e.g. houses, stocks and bonds):

(BUSLOANS = Commercial and Industrial Loans; REALLN = Real Estate Loans; LOANS = Loans and Leases at All Commercial Banks)

It should therefore come as no surprise that the transmission mechanism of monetary policy is now primarily through various asset markets (i.e. real estate monetary standard).

Consider the following charts showing various asset prices and inflation rates during the past 30 years:

Stocks:

High-Yield Corporate Debt:

Houses:

Inflation:

Over the past few years I’ve been very critical of the Federal Reserve’s actions spanning the last couple decades. One of the primary reasons behind this view was the incessant focus on limiting inflation and utter lack of concern regarding asset bubbles. The present risk of a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and QEternity lies mainly in inflating new asset bubbles, not creating excessive measured inflation. If the Fed has finally come back around to this realization, that would certainly be a big step in the right direction.

The beginning of a new year is apparently as good a time as any to start thinking about buying a new home. At the start of 2012 I found myself frequently engaged in discussions about whether or not it was finally the “right” time to buy a house. Mortgages with 30-year fixed rates were being offered around 4% and prices appeared to be stabilizing. Despite the widespread optimism, my conclusion was:

When deciding whether or not to purchase a home, there are certainly a whole host of factors to consider that were not discussed here (family, job security, income, savings/debt, location, etc). The purpose is to provide an alternative perspective to the seemingly common perception that now is the best time to buy and those who fail to act will miss a great opportunity. While I don’t rule out that possibility, I believe the outlook for home prices and mortgage rates suggests this window of opportunity will remain open for a few years. In fact, those who wait may be rewarded with lower mortgage rates and more house for their money. There is no rush to buy a home!

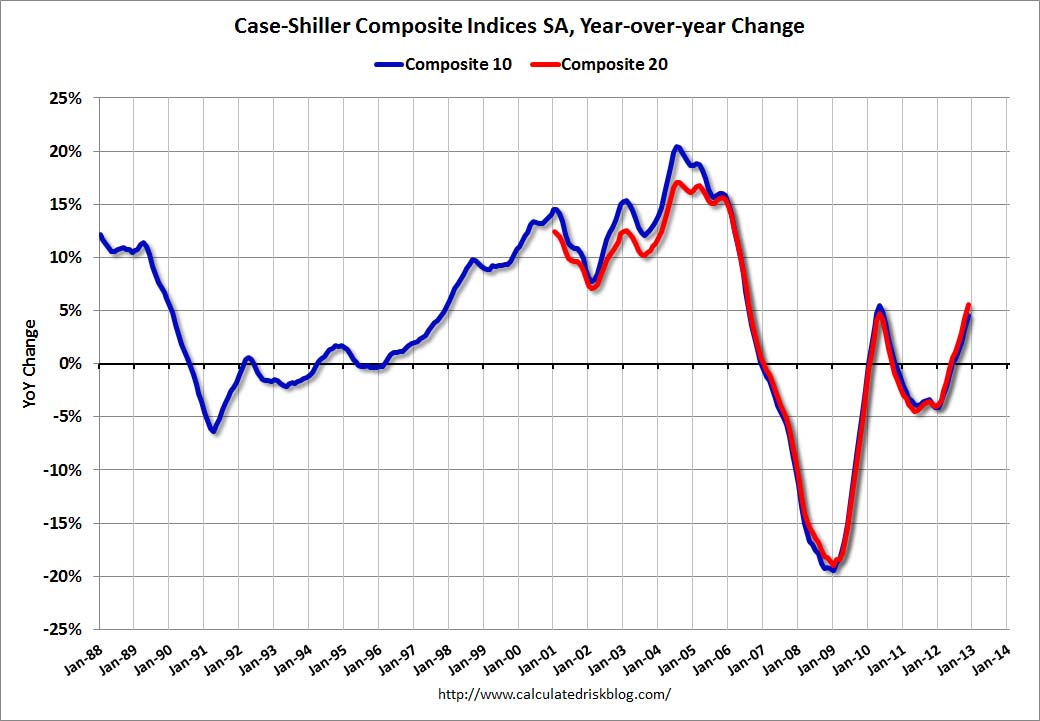

Now with the benefit of hindsight, my judgment appears to have held up relatively well. Although house prices have risen approximately 6 percent in the past year:

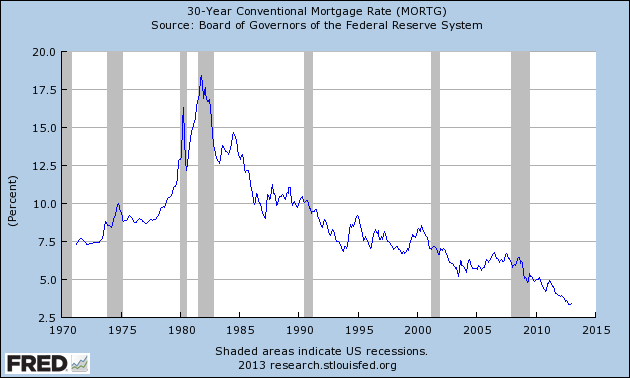

30-year fixed rate mortgages touched a new low of 3.3%: With 2013 only a month old, conversation among friends and family about buying new homes has picked up once again. Oddly enough, the substantial rise in prices over the past year is stoking demand for housing. (I say oddly because basic economics suggests demand should decrease when prices rise) However, before offering my views on future house prices, let me say a few words about mortgage rates.

With 2013 only a month old, conversation among friends and family about buying new homes has picked up once again. Oddly enough, the substantial rise in prices over the past year is stoking demand for housing. (I say oddly because basic economics suggests demand should decrease when prices rise) However, before offering my views on future house prices, let me say a few words about mortgage rates.

Over the past few months the FOMC has initiated QE3 (QEternity) and QE4, which involves purchasing $40 billion of Agency-MBS and $45 billion of Treasuries per month. Despite jubilant asset markets, inflation (core-PCE) and GDP growth remain well below 2 percent. This failure to stimulate real growth will likely lead the FOMC to extend its pledge of maintaining interest rates near 0 until at least 2016. Based on this combination of QE, ZIRP, low inflation, and stagnating growth, the chances of mortgage rates rising back above 4 percent anytime soon seems very limited.

Returning to the future direction of house prices, I remain skeptical that household balance sheets have been sufficiently repaired to permit a new debt-led boom. One of the better resources for housing market insights, Dr. Housing Bubble has highlighted the recent surge in investment demand. Meanwhile, Diana Olick discusses reports that Americans are tapping their homes for cash again. Clearly aspects of the previous bubble are returning, which makes it tough to rule out further gains in the short-term. That being said, US residential real estate just isn’t a great investment in real terms and here is Robert Shiller explaining why:

“Housing is traditionally is not viewed as a great investment. It takes maintenance, it depreciates, it goes out of style. All of those are problems. And there’s technical progress in housing. So, the new ones are better….So, why was it considered an investment? That was a fad. That was an idea that took hold in the early 2000′s. And I don’t expect it to come back. Not with the same force. So people might just decide, ‘yeah, I’ll diversify my portfolio. I’ll live in a rental.’ That is a very sensible thing for many people to do.

…From 1890 to 1990 the appreciation in US housing was just about zero. That amazes people, but it shouldn’t be so amazing because the cost of construction and labor has been going down.

…They’re not really an investment vehicle unless you want it for your personal reasons.”

If you want more proof, here is the chart Shiller is referencing:

My recommendation therefore remains basically the same as last year. Housing prices and mortgage rates may have bottomed, but the odds of either rising substantially in the next couple years remains small. Ultimately you should buy a house that you want to live in, not that you hope will be a good investment. If you plan on buying, just remember, there is no rush to buy a home!

1) Hit the “Defer” Button, Thanks… by David Merkel @ The Aleph Blog

This is why I believe that the biggest issue in restoring prosperity globally, is finding ways to have creditors and stressed debtors settle for less than par on debts owed. Move back to more of an equity culture from what has become a debt culture. A key aspect of that would be making interest paid non-tax-deductible for corporations, housing, etc., while making dividend payments similar to REITs, while not requiring payouts equal to 90% of taxable income. Maybe a floor of 50% would work, with the simplifying idea that companies get taxed on their GAAP income — no separate tax income base. Would certainly reduce the games that get played.

Anyway, those are my opinions. The world yearns for debt relief, but governments and central banks argue with that, and in the short-run try to paper over gaps with additional short-term debt that they think they can roll over forever. They just keep trying to hit the “defer” button, avoiding any significant reforms, in an effort to preserve the “status quo.”

Woj’s Thoughts - After reviewing the results of my 2012 predictions, I mentioned:

My main takeaway is that politicians are far more determined to maintain the status quo than I had expected. The underlying economic (and social) problems have once again been kicked down the road for future governments to handle.

Although David’s policy recommendations are becoming increasingly pervasive, they unfortunately remain nowhere near the level necessary for governments to test uncharted waters.

2) Can Germans become Greeks? by Dirk @ econoblog101

The ECB as well as other policy makers and politicians do not understand economics. They think that a simple recipe like “decrease government spending, export more” is enough to solve the euro zone crisis. The increase in government debt is a symptom of the crisis, not a cause. The cause of rising government debt was negative economic growth and bank bail-outs. These are the two problems which must be tackled. They are intertwined, so solutions should address both. Households cannot pay their mortgages in Spain and Ireland at the existing unemployment levels, and that is due to a lack of demand as households consume less and save more. This downward spiral must be stopped and turned around, since at negative growth rates even a government debt of €1 is too high.

It seems that instead of Greeks becoming Germans now the German are becoming Greeks. That means that without government spending Germany will not have positive growth rates. While this will come as a surprise to many, it shouldn’t be.

Woj’s Thoughts - Germany managed to run a slight fiscal surplus during 2012 that ultimately came at the expense of growth. In the fourth quarter, German GDP shrank by 0.5 percent. Meanwhile, attempts at structural reform (i.e. fiscal consolidation) in the European periphery appear to be speeding up the rise in unemployment and decline in growth. This dynamic is neither economically or socially sustainable, therefore the governments and ECB must either substantially change the current course or wait for countries to eventually exit the Eurozone.

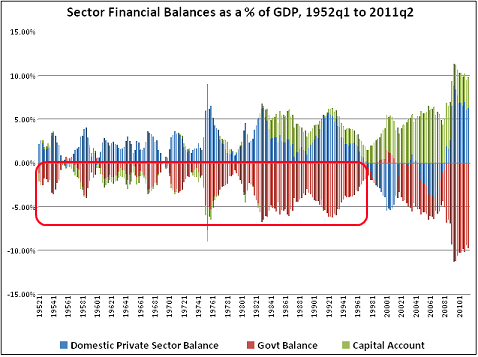

3) Did We Have a Crisis Because Deficits Were Too Small? by JW Mason @ The Slack Wire

The logic is very clear and, to me at least, compelling: For a variety of reasons (including but not limited to reserve accumulation by developing-country central banks) there was an increase in demand for safe, liquid assets, the private supply of which is generally inelastic. The excess demand pushed up the price of the existing stock of safe assets (especially Treasuries), and increased pressure to develop substitutes. (This went beyond the usual pressure to develop new methods of producing any good with a rising price, since a number of financial actors have some minimum yield -- i.e. maximum price -- of safe assets as a condition of their continued existence.) Mortgage-backed securities were thought to be such substitutes. Once the technology of securitization was developed, you also had a rise in mortgage lending and the supply of MBSs continued growing under its own momentum; but in this story, the original impetus came unequivocally from the demand for substitutes for scarce government debt. It's very hard to avoid the conclusion that if the US government had only issued more debt in the decade before the crisis, the housing bubble and subsequent crash would have been much milder.

Woj’s Thoughts - The scenario laid out by JW sounds equally plausible and compelling to me. Changes in tax policies during the 1980’s and 1990’s set the stage for massive increases in real estate loans and the corresponding housing price boom. Then the unmet demand for safe-liquid assets prompted both the rise of shadow banking and the dispersion of U.S. housing assets to the rest of the world. So as the last sentence attempts to make clear, the “crash would have been much milder” but a similar crisis would likely have occurred.

Michael Sankowski, at Monetary Realism, asks us to consider the possibility that we are on a Real Estate Monetary Standard:

I’ve been thinking a lot about this over last few weeks when I have the chance to think. It seems like we are on a real estate monetary standard. Much like how we can use assets like gold to create a commodity money system, it seems like we operate our current monetary system as a real estate standard.

Banks create money against real estate assets. We use this money in our day-to-day transactions, without much thought about what stands behind this money, but most loans are for residential and commercial real estate.

If we did operate under a real estate standard, we would expect to see the larger economic business cycle greatly impacted by the real estate cycle, far more than the declines in real estate activity would predict.

The impetus for this discussion is a recent paper by Ed Leamer, “Housing is the Business Cycle,” that confirms Mike’s prediction. The following graph shows real estate loans at all commercial banks as a percentage of total loans and leases: Notice that the percentage held relatively steady around 25 percent for nearly 40 years following the end of WWII. Then, in the mid-1980’s, the percentage surged higher. This massive change may have been a consequence of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 that included “ increasing the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction,” a “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” and changes to “ the treatment of imputed rent, local property taxes, and mortgage interest payments to favor homeownership.” After leveling off in the mid-1990’s, the percentage of real estate loans once again spiked higher beginning in late 1998. Once again, changes in tax policy may have played a substantial role. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 substantially lowered the capital gains rate and “exempted from taxation the profits on the sale of a personal residence of up to $500,000 for married couples filing jointly and $250,000 for singles.”

Notice that the percentage held relatively steady around 25 percent for nearly 40 years following the end of WWII. Then, in the mid-1980’s, the percentage surged higher. This massive change may have been a consequence of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 that included “ increasing the Home Mortgage Interest Deduction,” a “Low-Income Housing Tax Credit,” and changes to “ the treatment of imputed rent, local property taxes, and mortgage interest payments to favor homeownership.” After leveling off in the mid-1990’s, the percentage of real estate loans once again spiked higher beginning in late 1998. Once again, changes in tax policy may have played a substantial role. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 substantially lowered the capital gains rate and “exempted from taxation the profits on the sale of a personal residence of up to $500,000 for married couples filing jointly and $250,000 for singles.”

The shifting of bank lending from primarily commercial to real estate loans has clearly been accompanied by shifts in policy to vastly reduce taxes accompanying rents, interest and capital gains. These changes, as well as other public policy initiatives, have helped significantly increase the value of homes that could be borrowed against. As Michael Hudson argues in The Bubble and Beyond, the overall effect has been to transfer former tax payments to private financial institutions, ultimately increasing wealth inequality and making the economy (and government) more beholden to the banks.

Although total real estate loans have actually fallen during the past few years, they still account for nearly 50 percent of total loans. This real estate monetary standard is certainly not restricted to the U.S. and actually appears to be prominent in Europe, as well as several other developed nations. To the degree that bank lending affects aggregate demand, real estate will clearly continue to have an outsized effect on the global business cycle.

(Note: For those interested, Leamer actually discussed this paper during an episode of EconTalk with Russ Roberts back in May 2009.)

Last year I took a chance and threw my own projections into the ring. Similar to Byron Wien and Edward Harrison, I mostly selected events that were widely seen as having a low probability (less than 33%) but which I believed held a greater than 50% chance of occurring. Let’s see how I did...

1) Greece leaves the Euro - As the year progresses the Greek economy continues to contract and unemployment continues to rise, surpassing 50% for youth. This combination of factors offsets attempts to reduce the budget deficit as the country repeatedly misses EU and IMF required targets. Despite potential for further bailouts, the Greek people finally decide the consequences of tied promises outweigh the benefits of remaining in the Euro. Greece defaults on all debts, returning to a heavily depressed drachma.

Result - Wrong (0-1). During 2012, Greece was successful in reducing its budget deficit by 30 percent and staying in the Eurozone. This success was in large part due to further defaults on public debt and another bailout. Unfortunately for the Greek people. the price of these efforts remains extraordinarily high. The economy may have contracted as much as 6.5 percent in 2012, the fifth year of recession, according to forecasts in the 2013 budget. Meanwhile both the general and youth unemployment rates continue to soar, reaching ~27 percent and ~58 percent, respectively. At this point Greece is clearly in the midst of a Depression and showing no signs of recovering anytime soon. Greek tolerance of increasing unemployment and decreasing prosperity remains a surprise, although radical political parties have been gaining support. For now Greece remains in the Eurozone, but a future exit remains likely.

2) Italy and Spain lose access to credit markets - A Greek default raises concerns about the potential for creditors to face actual losses on EU sovereign debt. The ECB’s measured efforts are not strong enough to overcome fear and concern about future growth in Italy and Spain. Deep recessions take hold in both countries, pushing deficits higher.

Result - Wrong (0-2). A Greek default and concerns about the European economy weighed heavily on EU sovereign debt during the first half of the year. By the summer, ten-year bond yields in Spain and Italy were at 7.75 percent and 6.75 percent, respectively, and rising. With the countries at risk of losing access to credit markets, ECB President Mario Draghi came forth with a plan to cap sovereign interest rates using open-ended outright monetary transactions (OMT). Draghi’s threat was enough to generate a 180 degree turn in EU sovereign debt markets, but nowhere near enough to turn around the economies. Italy and Spain both returned to recession this past year, pushing fiscal deficits and unemployment higher. While Italy’s unemployment rate remains closely tied to the EU-wide level of ~11 percent, Spain’s general and youth unemployment rates have quickly caught up to Greece’s levels. Eventually Draghi’s Liquidity Bluff Will Be Called, potentially sooner rather than later as a strengthening euro may reignite the EU crisis.

3) The Eurozone enters recession - Practically the entire Eurozone falls into recession, including the likes of France and Germany. A deteriorating economic outlook causes deficit estimates to be raised across the board, facilitating credit rating downgrades. Agreements for greater austerity fail to stem the tide and other attempts to kick the can down the road are pursued.

Result - Correct (1-2). The euro zone economy contracted 0.2 percent in the second quarter and 0.1 percent in the third, meeting the technical definition of a recession. The fourth quarter drop is looking even worse following recent news that Germany saw output shrink 0.5 per cent between October and December. Although Germany managed to run a slight fiscal surplus, at the expense of growth, Spain’s budget deficit probably exceeded 9 percent for a fourth year in 2012. The first half of the year did witness credit downgrades and austerity agreements, but Draghi’s big kick at the end of summer pushed any further actions into future years.

4) China’s GDP growth falls below 7% - As exports to Europe contract, the busting of China’s housing bubble continues unabated. Expectations for massive monetary easing in Europe and the US, along with fear of flare ups in the Middle East sets a floor under energy and food commodity prices. Monetary easing and fiscal stimulus in China are applied too slowly to prevent growth from slowing below the supposedly necessary 8%. (Note: This will be not be considered a hard-landing, which I deem growth below 5%. That may come in 2013, but for 2012 most economists/analysts will be able to maintain expectations of a soft-landing.)

Result - Wrong (1-3). During the third quarter China’s growth rate slowed to a three-year low of 7.4 percent, but the year-end tally will probably be around 7.7 percent. As growth slowed and housing prices fell early in the year, the government took action to allow a smoother transition between governments. Fiscal stimulus has pushed growth and inflation higher in the last few months, but at the expense of rebalancing the economy toward consumers for future sustainability.

5) Oil prices will spike above $120, finish year below $90 - (Using WTI crude prices, currently ~$102) At some point during the year Iran attempts to block the Strait of Hormuz. Further attempts to overthrow governments in the Middle East, possibly some that only recently gained power, hit the headlines again. Combined with global monetary easing, oil prices will move higher and gasoline will once again hit $4 per gallon in the US. These higher prices will exaggerate the reduction in global demand for other goods and push growth lower. As fears of a global recession take over, oil prices will fall, finishing the year down more than 10%.

Result - Wrong, but close (1-4). Fears about Iran and the Middle East never really materialized this year but that did not prevent a wild ride in oil prices. After rising to over $113 in April, WTI crude prices dropped all the way down to $80 in August (daily price history). A rally in the last week of the year brought the closing price slightly back above $90. Brent crude prices diverged significantly from WTI in 2012, keeping gas prices at the pump high throughout the summer. Gas prices peaked at $3.94, not quite $4, but nevertheless reached a record-high average of $3.62 per gallon.

6) US enters recession in 2nd half - Despite higher 4th quarter GDP in 2011, the lower savings rate and energy prices are unlikely to add much growth in 2012. With Europe contracting and China slowing down more than expected, US exports will take a hit. Extensions of the payroll tax cut and unemployment benefits will help ensure the federal deficit holds above 8%. Housing prices will continue to fall (based on Case-Shiller) causing the savings rate to once again reach 5%. By the end of 2012, the US will be in a recession (although NBER may not confirm this until 2013).

Result - Wrong (1-5). Despite Europe contracting, China slowing down and the federal deficit dropping to 7% (still over $1 trillion), US GDP growth remained positive throughout 2012. After falling to 1.3 percent in the second quarter, annualized GDP growth jumped to 3.1 percent in the third quarter. Although current estimates for fourth quarter GDP are below 1 percent, the US is most likely not in a recession at this time. Partially behind the positive growth was the impact of housing prices rising over 5 percent and the savings rate remaining below 4 percent.

7) Federal Reserve extends forecasts for ~0% rates until 2015 - As growth in the US weakens once again and the global economy slows, expected inflation over the next ten years (based on Cleveland Fed estimates) will fall towards 1%. With unemployment holding steady around 9%, the Fed will move it’s forecasts for the first interest rate hike out to 2015. (Some form of QE3 is also likely, but aside from promoting short-term speculation, the effects on growth are likely to be muted.)

Result - Correct (2-5). Expected inflation over the next ten years fell consistently during the course of the year to approximately 1.5 percent (chart below). Although unemployment improved materially, dropping below 8 percent, the Federal Reserve still felt the urge to step up monetary stimulus. On September 13th, 2012, the FOMC extended its projections for maintaining “exceptionally low levels for the federal funds rate...at least through mid-2015” while enacting a plan to purchase “additional agency mortgage-backed securities at a pace of $40 billion per month” indefinitely. Since QEternity was insufficient to boost growth, the Fed also enacted QE4 to raise the rate of balance sheet expansion.

8) President Obama will win re-election - Generally a weakening economy has been poor for incumbents but this time will be seen as abnormal circumstances. The troubles in Europe and high unemployment will actually spark desire for a more interventionist government. Given the choice between Obama and Romney, the President will win re-election by a slim margin (2% or less).

Result - Correct (3-5). President Obama crushed Romney in the 2012 election based on the electoral college, however the popular vote was decided by less than 3 percent.

9) The US dollar rises over 5% - (Based on dollar index) In spite of QE efforts and another sizable deficit, the US dollar retains its safe haven status. As fears of European defaults spread and China’s slowing growth impacts commodity prices, the dollar will continue to trend higher.

Result - Wrong (3-6). As fears spread about European default and a slowdown in China, the dollar rose several percent into the summer months. When those fears were assuaged by politicians, not economic data, the euro began a strong rally. By the end of the year, the dollar had essentially finished flat.

10) Bonds outperform stocks - The consensus once again favors stocks, although US Treasuries have now outperformed stocks over the past 1, 10 and 30 year horizons. With global growth slowing, inflation expectations will fall. Before this bull market in bonds ends, 10- and 30-year Treasuries may reach 1% and 2%, respectively.

Result - Wrong (3-7). Slowing global growth, falling inflation expectations and stagnating corporate earnings were not enough to deter stocks from a very strong performance in 2012. The Bernanke put morphed into a proactive Fed determined to push asset prices higher and succeeding to the tune of over 15 percent. While stocks were riding towards new highs, the bull market in bonds also remained intact. The 10- and 30-year Treasuries hit their respective lows of 1.43 and 2.46 during the summer before heading higher into year end. Ultimately 10- and 30-year Treasuries last year posted returns of only 3 percent and 2.5 percent, respectively.

That’s the end of it. 3-7 is certainly a bit of a disappointment, especially given the direction of events through the first half of the year. That being said, the logic behind each prediction was sound and far more on target than the end result suggests. My main takeaway is that politicians are far more determined to maintain the status quo than I had expected. The underlying economic (and social) problems have once again been kicked down the road for future governments to handle. As long as that pattern holds, current optimism and modest growth can persist for another couple years.

My hope is to have Predictions for 2013 out by the end of next week. Stay tuned.