Japan Does the Full Ponzi by Cullen Roche @ Pragmatic Capitalism

I saw this headline over at Calculated Risk regarding the new “monetary policy” in Japan:

And from the Japan Times: Japan’s economic minister wants Nikkei to surge 17% to 13,000 by MarchEconomic and fiscal policy minister Akira Amari said Saturday the government will step up economic recovery efforts so that the benchmark Nikkei index jumps an additional 17 percent to 13,000 points by the end of March.“It will be important to show our mettle and see the Nikkei reach the 13,000 mark by the end of the fiscal year (March 31),” Amari said in a speech.The Nikkei 225 stock average, which last week climbed to its highest level since September 2008, finished at 11,153.16 on Friday.“We want to continue taking (new) steps to help stock prices rise” further, Amari stressed …

…

Yes, the Bank of Japan might create some real wealth (for some market participants) in the near-term and might thereby make Japan appear better off than they really are, but there’s absolutely no underlying fundamental change in the corporations that make up this index that should lead one to believe that these price changes are justified. And when the Ponzi scheme is exposed the market collapses thereby destroying wealth for all the current participants leaving us right back where we started.

This is ponzi based monetary policy. It’s based on a false understanding of market dynamics, a false understanding of real wealth, and it’s very likely to cause disequilibrium in the long-term.

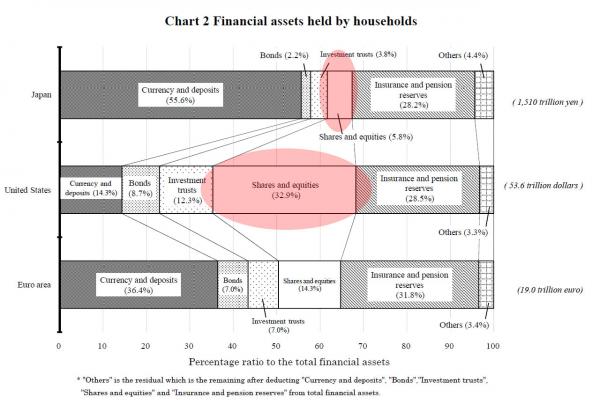

Woj’s Thoughts - While these comments made investors giddy, as expected, I can’t help but feeling that the continued onslaught of “open mouth” operations from Japanese officials is masking their deficient understanding of modern monetary economics. If wealth effects from higher stock prices are largely irrelevant in the U.S., what are the odds the effect will be greater in Japan where equities play a much smaller role in household portfolios?

As Niels Jensen makes clear in his most recent investor letter, the Nikkei’s recent surge combined with a plunging Yen suggests the pressures in both markets are arising primarily from foreign investors.

Prior to PM Abe taking office I was skeptical of fiscal and monetary policies actually being enacted that would materially raise either inflation or real GDP growth (effectively NGDP). Since then a minor fiscal stimulus package was announced along with a higher inflation target and commitment to future QE. Looking beyond the initial market optimism, none of these measures will actually generate the economic results to match the widespread wishful thinking. Fourth quarter NGDP was just recently announced at zero percent and real GDP fell for the third consecutive quarter. Unless further drastic policy actions are taken, I suspect future quarters will more closely resemble the current quarter than the hoped for 4% NGDP growth.

(Note: Cullen describes Japan’s theoretical new policy as a Ponzi scheme, but I think that terminology may be incorrect in this situation. Since the Bank of Japan (BoJ) can create an unlimited supply of reserves, it does not require any new lending to continually maintain any price for the Nikkei it chooses. The scariest outcome is not that the scheme would collapse, but that the BoJ would end up controlling all currently public corporations.

To be clear, I doubt that outcome would happen in practice. The more likely endgame is that the policy becomes politically unacceptable and then the BoJ retracting its price target leads to a spectacular (ponzi-esque) crash.)

"In practice, of course, the purists were unable to deliver, and the new tricks involve the 'modern macroeconomists' in ad hoc assumptions of their own that are at least as objectionable as the Keynesian macroeconomic generalizations that [Michael] Wickens objected to. We have already encountered one example, the 'Gorman preferences' needed to make the representative agent at least minimally plausible... Two others are equally incredible. The first is the 'no-bankruptcies' assumption in Walrasian models and the related 'No Ponzi' conditon that is imposed on D[ynamic] S[tochastic] G[eneral] E[quilibrium] models. This eliminates the possibility of default, and hence the fear of default (since these are agents with rational expectations, who know the correct model, and hence know that there is no possibility of default), and hence the need for money, since if your promise to pay is 'as good as gold', it would be pointless for me to demand gold (or any other form of money) from you. Money would be at most a unit of account, but never a store of value. The second is the unobtrusive postulate of 'complete financial markets', smuggled into Michael Woodford's Interest and Prices(Woodford 2003, p. 64), which means that all possible future states of the world are known, probabilistically, and can be insured against: this eliminates uncertainty, and hence the need for finance..." -- J. E. King, The Microfoundations Delusion: Metaphor and Dogma in the History of Macroeconomics (2012: p. 228)

This quote is the lead in a recent post by Robert Vienneau putting forth the question, “Can General Equilibrium Theory find a role for money?” During my first semester in a PhD Economics program, application of the ‘No Ponzi’ condition appeared almost universal in macroeconomic models. At points I tried to raise the question of how removing this condition would impact results from the various models. Although a sufficient answer, at least for me, was not forthcoming, it appeared as though that condition was necessary to ensure a general equilibrium existed.

As for the inclusion of ‘complete financial markets’, I am not yet familiar with Woodford’s book, mentioned above. Having worked in financial markets for a few years, the notion of probabilistic uncertainty is not only false but completely misses an important aspect of investing. The purpose of holding various levels of cash over time is specifically because future states and their probabilities are unknown.

On the whole, general equilibrium models appear to remain consistent with the classical view of commodity trade, C-M-C' (a commodity is sold for money, which buys another, different commodity with an equal or higher value). Meanwhile two other views, put forth to account for a financial sector by Marx, have been largely ignored:

1) M-C-M' (money is used to buy a commodity which is resold to obtain a larger sum of money)

2) M-M' (a sum of money is lent out at interest to obtain more money, or, one currency or financial claim is traded for another. "Money begets money.")

Based on my initial exposure to advanced macroeconomics, it appears true that “money would be at most a unit of account, but never a store of value.”

What do I mean by Ponzi Austerity? It is not just a case of pretend austerity of the sort that we had, say, in the UK under Mrs Thatcher, when education, health etc. were cut back with a vengeance, in austerity’s name, while the public sector’s borrowing requirement grew on the back of a massive expansion of the state’s (primarily centralised, authoritarian) activities (and all in the name of a ‘smaller’ state). No, Ponzi Austerity requires more than that. It requires the symbiosis of:

(a) large scale reductions in public services and a squeeze on the taxpayer (in the name of reining in public finances), and of

(b) a new mechanism for refinancing the debt of one branch of the macro-economy (including bank losses) by creating new unsustainable debts in some other branches.

In short, Ponzi Austerity increases aggregate debt intentionally by shifting it about the macroeconomy in the hope that the public’s eye will be distracted from all this movement, time will purchased by the powers-that-be at the expense of solvency and, in the end, those with the most to gain from taking their money out of the ‘system’ before they inevitable collapse will manage to do so, leaving the hapless taxpayer to pick up the pieces when the whole thing ends up belly-up. One only needs to look furtively at what is happening in Europe today in order to draw the unavoidable conclusion that the austerity practiced in the Eurozone today is perhaps the most glaring case of Ponzi Austerity possible.

From Ponzi Growth to Ponzi Austerity

By Yanis Varoufakis

Related posts:

What is Austerity?

The Austerity Experiment Failed Without Really Starting

Krugman Reveals New, Flawed Definition of Austerity

Valuing the Future Over the Here and Now