Ashwin Parameswaran has a fantastic post today explaining why Helicopter Money Is Not Dangerous, All Macroeconomic Policy Is Dangerous “in the sense that irresponsible implementation can lead to macroeconomic chaos.” Before jumping into the main attraction of the post, I want to briefly clarify a general discrepancy regarding what helicopter money actually entails.

More than forty years ago, Milton Friedman famously quipped that price deflation can be fought by "dropping money out of a helicopter."[37] Friedman was referring to central bank policy and, to this day, a “helicopter drop” is typically associated with monetary policies, such as quantitative easing (QE). This is an unfortunate interpretation of monetary policy since most central banks, including the Federal Reserve, are as equally unable to actually implement a “helicopter drop” today as they were back in 1969. Willem Buiter clarifies how the policy could realistically be implemented in a paper on “Helicopter Money” (equations omitted):

Technically, if the Central Bank could make transfer payments to the private sector, the entire (real-time) Friedmanian helicopter money drop could be implemented by the Central Bank without Treasury assistance.

…

The legality of such an implementation of the helicopter drop of money by the Central Bank on its own would be doubtful in most countries with clearly drawn boundaries between the Central Bank and the Treasury. The Central Bank would be undertaking an overtly fiscal act, something which is normally the exclusive province of the Treasury.47

An economically equivalent (albeit less entertaining) implementation of the helicopter drop of money would be a tax cut (or a transfer payment) implemented by the Treasury, financed through the sale of Treasury debt to the Central Bank, which would then monetise the transaction. If the direct sale of Treasury debt to the Central Bank (or direct Central Bank lending to the Treasury) is prohibited (as it is for the countries that belong to the Euro area), the monetisation of the tax cut could be accomplished by the Treasury financing the tax through the sale of Treasury debt to the domestic private sector (or overseas), with the Central Bank purchasing that same amount of non-monetary interest bearing debt in the secondary market, thus expanding the base money supply. (2004: p. 59-60)

One might inquire whether changing to a “permanent floor” monetary policy regime alters the necessity of monetisation. Apparently prepared for such a future outcome, Buiter says:

This difference between the effects of monetising a government deficit and financing it by issuing non-monetary debt persists even if the interest rates on base money and on non-monetary debt are the same (say zero), now and in the future. When both money and bonds bear a zero nominal interest rate, there remains a key difference between them: the principal of the bonds is redeemable, the principal of base money is not. (2004: p. 10)

Although monetisation may be necessary to achieve the full effect of “helicopter money,” this practice does not alter the dangers associated with the Treasury’s actions. As Ashwin points out:

Whether they are monetised or not, excessive fiscal deficits are inflationary.

On the topic of inflation, I have recently been engaging in a debate with Mike Sax (see here and here) about the potential benefits of targeting a higher inflation rate. This policy has garnered support from both sides of the political and economic aisle (New Keynesians and Monetarists), yet I think its potential benefits are being extremely oversold. My two basic arguments against such a policy are the following:

1) Higher inflation does not necessarily entail higher nominal wages (which many people clearly assume).

Aside from the top quintile of households, real income has been declining for nearly 15 years. The only way higher inflation helps reduce real debt burdens is if nominal wages increase faster than nominal interest rates on debt. If instead higher inflation stems primarily from higher costs-of living (nominal food and energy prices), than most Americans may find themselves in the precarious position of requiring even more debt to maintain current living standards.

2) Higher inflation alters saving, investment and consumption decisions which can lead to a misallocation of capital. On this second point is where Ashwin’s post really hits home:

During most significant hyperinflations throughout history, the catastrophic phase where money loses all value has been triggered by the central bank’s enforcement of highly negative real interest rates which encourages the rich and the well-connected to borrow at negative real rates and invest in real assets. The most famous example was the Weimar hyperinflation in Germany in the 1920s during which the central bank allowed banks and industrialists to borrow from it at as low an interest rate of 5% when inflation was well above 100%. The same phenomenon repeated itself during the hyperinflation in Zimbabwe during the last decade (For details on both, see my post ‘Hyperinflation, Deficits and Real Interest Rates’).

This also highlights the danger in simply enforcing a higher inflation target without taking the level of real interest rates into account. For example, if the Bank of England decided to target an inflation rate of 6% with the bank rates remaining at 0.50%, the risk of an inflationary spiral will increase dramatically as more and more private actors are tempted to borrow at a negative real rate and invest in real assets. Large negative real rates rarely incentivise those with access to cheap borrowing to invest in businesses. After all, why bother with building a business when borrowing and buying a house can make you rich? Moreover, just as was the case during the Weimar hyperinflation, it is only the rich and the well-connected crony capitalists and banks who benefit during such an episode. If the “danger” from macroeconomic policy is defined as the possibility of a rapid and spiralling loss of value in money, then negative real rates are far more dangerous than helicopter money.

These pernicious traits of higher inflation and especially negative real interest rates are entirely compatible with recent experience. Households and businesses “with access to cheap borrowing” have been pouring money into stock, bond, housing and commodity markets rather than investing in tangible capital. The remarkable rise in asset prices has unfortunately not funneled down to households in the bottom four quintiles of income and wealth, only furthering the inequality gap. Recognition of these effects is precisely why a Federal Reserve fearing bubbles, not inflation, would be a significant step in the right direction.

To be clear, similar to Ashwin, I am in favor of “helicopter money” and believe higher wages for the bottom 80 percent are key to ending the balance sheet recession as well as ensuring more sustainable growth and unemployment going forward. Targeting higher inflation and larger negative real interest rates is the wrong approach to achieve these goals and may actually work in the opposite direction. Yes, all macroeconomic policy is dangerous. But even more dangerous is misunderstood and misrepresented macroeconomic policy.

Bibliography

Buiter, Willem H., Helicopter Money: Irredeemable Fiat Money and the Liquidity Trap (December 2003). NBER Working Paper No. w10163. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=478673

The Impossible Trinity (also known as the Trilemma) is a trilemma in international economics which states that an economy cannot simultaneously maintain a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement, and an independent monetary policy. This principle was initially derived from the Mundell-Fleming model, also known as the IS-LM-BoP model. Although the model was first outlined by Mundell and Fleming 50 years ago, to this day it continues to play a significant role informing public policy. For this reason it also remains a staple of Ph.D. programs, even those that generally despise Keynesian economics.

While many students may accept the model’s conclusions based on its longevity and the professions’ widespread adherence (which may be wise), I was naturally skeptical. What are the model’s assumptions? Will different monetary regimes alter the conclusions? What does it even mean to have “an independent monetary policy”? In search of answers, I sought out one of the original sources.

“Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates” by R.A. Mundell was published in The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science all the way back in November 1963. At the time the world’s major industrial nations were adhering to the Bretton Woods system, under which the U.S. dollar was convertible to gold and all other countries involved tied their currencies to the U.S. dollar. Recognizing the expansion of global trade taking place, Mundell sought to outline “the theoretical and practical implications of the increased mobility of capital. (p.475)” To simplify the conclusions Mundell begins by assuming “the extreme degree of mobility that prevails when a country cannot maintain an interest rate different from the general level prevailing abroad. (p.475)” He further assumes “that all securities in the system are perfect substitutes” and therefore the “existing exchange rates are expected to persist indefinitely. (p.475)” The last assumption presently worth noting is that “Monetary policy will be assumed to take the form of open market purchases of securities. (p.476)”

While these assumptions may have been valid within the Bretton Woods system, that system was terminated in 1971 by President Nixon unilaterally canceling the direct convertibility of the U.S. dollar to gold. Since then the U.S. and several other major industrial nations have been operating using a fiat currency. Under this new monetary regime, without convertibility, there is little reason to believe that all currencies are even near perfect substitutes or that exchange rates will persist for any defined period of time. Furthermore the end of the Bretton Woods system marked the beginning of inflation targeting as the primary method of monetary policy.

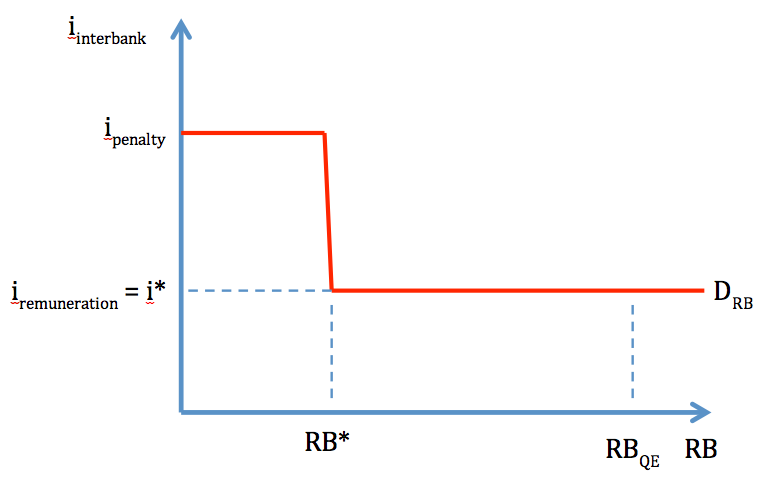

Monetary policy was still enacted through open market operations after the regime change, but those operations were now performed to maintain an target interest rate. The more significant difference is that using interest rates as the primary tool for targeting inflation ensured interest rates would be maintained at levels different from those prevailing abroad. This “corridor” system of inflation targeting would last in the U.S. for nearly 40 years before being replaced by a “permanent floor” system in 2008.

Breaking with previous tradition, the “permanent floor” system (also known as interest-on-reserves regime) allows central banks to control interest rates separate from engaging in open market operations. Interest rates are now (largely) determined by the interest-on-reserves (IOR) rate, while excess reserves give the central bank freedom to let the monetary base fluctuate more widely.

Returning to Mundell’s paper, he begins by analyzing monetary policy under flexible exchange rates:

“Consider the effect of an open market purchase of domestic securities in the context of a flexible exchange rate system. This results in an increase in bank reserves, a multiple expansion of money and credit, and downward pressure on the rate of interest. But the interest rate is prevented from falling by an outflow of capital, which causes a deficit in the balance of payments, and a depreciation of the exchange rate. In turn, the exchange rate depreciation (normally) improves the balance of trade and stimulates, by the multiplier process, income and employment. A new equilibrium is established when income has risen sufficiently to induce the domestic community to hold the increased stock of money created by the banking system. Since interest rates are unaltered this means that income must rise in proportion to the increase in the money supply, the factor of proportionality being the given ratio of income and money (income velocity). (p.477)”

The earlier review of changes to the monetary regime makes it clear that this causal chain is fraught with errors. Starting from the beginning, “an increase in bank reserves” does not cause “a multiple expansion of money and credit” (see here) nor will it lead to “downward pressure on the rate of interest.” If interest rates are unchanged, there should be no outflow of capital and no subsequent depreciation of the exchange rate. The balance of trade therefore remains the same and the “multiplier process” never takes place. In complete contrast to Mundell’s conclusion, monetary policy (effectively QE) has no effect on income or employment under flexible exchange rates.*

Switching to monetary policy under fixed exchange rates:

“A central bank purchase of securities creates excess reserves and puts downward pressure on the interest rate. But a fall in the interest rate is prevented by a capital outflow, and this worsens the balance of payments. To prevent the exchange rate from falling the central bank intervenes in the market, selling foreign exchange and buying domestic money. The process continues until the accumulated foreign exchange deficit is equal to the open market purchase and the money supply is restored to its original level. (p. 479)”

As previously stated, the creation of excess reserves no longer affects the interest rate. This prevents the rest of Mundell’s process from taking place, but nonetheless results in the conclusion that monetary policy is ineffective.

This fixed exchange rate simulation serves as the basis for the Impossible trinity. Given free capital flows and a fixed exchange rate, the central bank is forced to counteract open market operations with equivalent opposing actions in the foreign exchange market. Since the money supply is ultimately unchanged, the country is said to have relinquished its monetary policy independence. However, under the current monetary policy regime this outcome is drastically altered.

Mundell examines the common case of a country trying “to prevent the exchange rate from falling. (p. 479)” Using a “permanent floor” system the central bank can maintain its interest rate policy and a fixed exchange rate, but faces limitations since “the central bank intervenes in the market, selling foreign exchange and buying domestic money. (p. 479)” One limitation arises when the central bank runs out of salable foreign exchange. Another limitation occurs once the central bank drains all excess reserves from the system, forcing it to forgo either its interest rate or exchange rate policy. These limitations suggest the Impossible Trinity will hold in the long run.

Now consider the less frequent and more recent case of a country trying to prevent its exchange rate from rising. The central bank manipulates the market exchange rate by buying foreign exchange and selling domestic currency. Contrary to the previous example, the central banks actions suddenly appear unlimited. Since the central bank can always create new reserves, it faces no limitations in selling domestic currency. Meanwhile if the demand to trade foreign exchange for domestic currency dries up, then the central bank will have successfully defended its peg. Therefore, as long as the Fed is willing to accept the risks associated with a balance sheet full of foreign exchange, the Impossible trinity is no longer impossible.

The Impossible trinity stems from Mundell and Fleming’s attempt to incorporate an open economy into the IS-LM model. Their analysis reflects an understanding of the Bretton Woods system, which ruled monetary policy at that time. Today’s monetary system and policy operations are a far cry from the Bretton Woods system, yet the Mundell-Fleming model has not been updated accordingly. Beyond minimizing the effects of monetary policy, the transformation of monetary policy to a “permanent floor” system has made the previously impossible, possible.

*In reality, monetary policy (QE) will affect income and employment to some degree for reasons not outlined by Mundell. However, those effects are likely to be small and could be either positive or negative.

Related posts:

Does the Permanent Floor Affect the Inflationary Effects of the Platinum Coin?

The Permanent Floor and Potential Federal Reserve 'Insolvency'

Fed's Treasury Purchases Now About Asset Prices, Not Interest Rates

The Money Multiplier Fairy Tale

Currency Intervention and the Myth of the Fundamental Trilemma

IOR Killed the Money Multiplier

Despite Hicks' Denouncing His IS-LM Creation, The Classroom Gadget Lives On

Bibliography

Mundell, R. A. "Capital Mobility and Stabilization Policy under Fixed and Flexible Exchange Rates." The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science 29.4 (1963): 475-85. Print.

1) Nine facts about top journals in economics by David Card and Stefano DellaVigna @ VoxEU.org

Second, as Figure 2 shows, the total number of articles published in the top journals declined from about 400 per year in the late 1970s to around 300 per year in 2010-12. The combination of rising submissions and falling publications led to a sharp fall in the aggregate acceptance rate, from around 15% in 1980 to 6% today. Currently, QJE is the most selective of the top-five journals, with an acceptance rate of around 3%, followed by JPE and RES, with acceptance rates of around 5%. The least selective of the top-five are AER and Econometrica, with acceptance rates of around 8%.

Figure 2. Number of articles published per year

Notes: Publications exclude notes, comments, announcements, and Papers and Proceedings. Totals for 2012 estimated.

Over time, and especially during the last 15 years, it has become increasingly difficult to publish in the top five journals. Other things equal, this suggests that hiring and promotion benchmarks based on top-five publications (e.g., “at least one top-five publication for tenure”) are significantly harder to reach. (emphasis added)

Woj’s Thoughts - Although I can’t find a link at the moment, recent work in this field also shows the age of author’s publishing in the top journals rising over the past several years. As an aspiring academic in the field of economics, the combination of these results is slightly demoralizing. However, the recent introduction of a few new journals provides reason to hope the landscape may be changing. The path forward will be difficult in either case, but I have faith that hard work and persistence will ultimately lead to attainment of my professional goals.

2) The Coin is Dead! Long Live the Coin! by Michael Sankowski @ Monetary Realism Noah Smith asks a funny question on Twitter:

Noah Smith asks a funny question on Twitter:

”Hey, anyone remember the trillion dollar coin? ^_^ ”

I’d say Paul Krugman and Steve Waldman remember the trillion dollar coin quite well. So do all of the people listed by Steve Waldman in the beginning (and the end, Frances and Ashwin!) of his post.

The coin was only an idea, only supposed to spark a debate about the ability of the government to issue money directly. It was a big, shiny lure dangling in front of fish.

Then, the debt ceiling came along and changed the coin from “funny and interesting idea” to “necessary if we want to avoid an economic meltdown“. That debate catapulted the coin to fame, and fortunately kickstarted the debate Paul K, Steve W and others are having now.

Woj’s Thoughts - With an apparent temporary resolution to the debt ceiling, this debate has died down over the past several days. For those who might not normally read through the comments sections, I highly recommend making an exception for the discussions that took place on Scott Fullwiler’s post and all of Waldman’s. If that’s asking too much, at least check out my contributions to the debate (see here, here, and here) because as Mike notes, “ Joshua Wojnilower (Woj) gets it right away.”

3) Is Chinese re-balancing bullish? by Cam Hui @ Humble Student of the Markets

Rebalancing = Growth slowdown

So a move to re-balance growth to the household sector good news and bullish for stocks and risky assets? Well, not in the short term. Here is Pettis' arithmetic:

"But let us...give China five years to bring investment down to 40% of GDP from its current level of 50%. Chinese investment must grow at a much lower rate than GDP for this to happen. How much lower? The arithmetic is simple. It depends on what we assume GDP growth will be over the next five years, but investment has to grow by roughly 4.5 percentage points or more below the GDP growth rate for this condition to be met.

If Chinese GDP grows at 7%, in other words, Chinese investment must grow at 2.3%. If China grows at 5%, investment must grow at 0.4%. And if China grows at 3%, which is much closer to my ten-year view, investment growth must actually contract by 1.5%. Only in this way will investment drop by ten percentage points as a share of GDP in the next five years.

The conclusion should be obvious, but to many analysts, especially on the sell side, it probably needs nonetheless to be spelled out. Any meaningful rebalancing in China’s extraordinary rate of overinvestment is only consistent with a very sharp reduction in the growth rate of investment, and perhaps even a contraction in investment growth." (quotation marks added for clarity)

Woj’s Thoughts - Many analysts, not including Cam or Michael Pettis, continue to under appreciate the degree to which actual re-balancing in China will dampen growth prospects. This is precisely the difficult policy decision facing China’s leaders today. So far, China has responded to slower growth by increasing investment (fiscal stimulus) and thereby reversing re-balancing efforts. While this will likely boost GDP in the short-term (as seen in Q4 2012), correspond increases in “financial fragility” will only serve to exacerbate the downside in the longer-run.

After furthering understanding of the permanent floor, I discussed how that monetary regime might affect the inflationary effects of the “platinum coin.” Although the debate appears to be dying down, at least momentarily, Simon Wren-Lewis and Frances Coppola (see here, here, and here) have added worthwhile readings.

In concluding my brief series on this topic, I will address questions regarding potential Federal Reserve insolvency and the desirability of permanently practicing monetary policy under a “floor” system. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Q: The Federal Reserve has recently been turning over to the Treasury approximately $80 billion in profits each year, stemming from the yield spread between their assets and liabilities. As the Fed eventually raises interest rates on reserves (assuming the “permanent floor” system remains in place), that yield spread could turn negative, representing losses for the Fed. If the Fed’s capital is entirely drained, can it continue to pay interest on liabilities (e.g. reserves) or must it first be recapitalized? If the latter, does this require Congressional approval, Treasury action, or some other mechanism?

A: Before trying to put forth an answer, I should note that the present likelihood of this scenario becoming a reality is extremely small and would probably be preceded by much higher inflation (and interest rates). As several commenters noted, finding a direct answer to this question is extremely difficult. Courtesy of Dan Kervick:

Here is a 2002 General Accounting Office report that discusses some of these issues:

http://www.gao.gov/assets/240/235606.pdf

From the “Results in Brief” section at the beginning:

The Reserve Banks use their capital surplus accounts to act as a cushion to absorb losses. The Financial Accounting Manual for Federal Reserve Banks says that the primary purpose of the surplus account is to provide capital to supplement paid-in capital for use in the event of loss. Federal Reserve Board officials noted that the capital surplus account absorbs losses that a Reserve Bank may experience, for example, when its foreign currency holdings are revalued downward. Federal Reserve Board officials noted, however, that it could be argued that any central bank, including the Federal Reserve System, may not need to hold capital to absorb losses, mainly because a central bank can create additional domestic currency to meet any obligation denominated in that currency. On the other hand, it can also be argued that maintaining capital, including the surplus account, provides an assurance of a central bank’s strength and stability to investors and holders of its currency, including those abroad. The growth in the Reserve Banks’ capital surplus accounts can be attributed to growth in the size of the banking system together with the Federal Reserve Board’s policy of equating the amount in the surplus account with the amount in the paidin capital account. The level of the Federal Reserve capital surplus account is not based on any quantitative assessment of potential financial risk associated with the Federal Reserve System’s assets or liabilities. According to Federal Reserve officials, the current policy of setting levels of surplus through a formula reduces the potential for any misperception that the surplus is manipulated to serve some ulterior purpose. In response to our 1996 recommendation that the Federal Reserve Board review its policies regarding the capital surplus account, it conducted an internal study that did not lead to major changes in policy.

Based on this paragraph and corresponding discussion, the best current answer is that negative equity would not prevent the Fed from pursuing its desired monetary policy since “a central bank can create additional domestic currency to meet any obligation denominated in that currency.” If the Fed truly desired to maintain a capital surplus, to signal “strength and stability to investors and holders of its currency,” than one option is raising service fees charged to banks. This action would represent a tightening of monetary policy, but that could be desirable at the time.

If that course is not pursued, the other plausible action appears to be a Congressionally approved capital transfer from the Treasury. Although this action could be contended by politicians that oppose the Fed, the reality is that failure to provide capital would not alter the Fed’s ability to act or remain independent. Furthermore, a contentious Congressional battle on this otherwise insignificant matter could undermine the Dollar’s status as a reserve currency (similar to the debt ceiling debates). Provided this view is reasonably accurate, there appears little reason to fear the Fed losing its capital or as some argue, becoming ‘insolvent’.

Q: If the Fed leaves the zero lower bound (ZLB), is there any good reason to keep reserves in chronic excess?

A: Yes. An “interest-on-reserves regime” or “permanent floor”, where reserves are kept in chronic excess, allows the Fed to exogenously determine the monetary base AND interest rate. Therefore, if the Fed wishes to exit the ZLB it must either sell treasuries and Agency-MBS until excess reserves are practically eliminated (reverse QE) or increase the interest rate on reserves (IOR) to set a floor for the interbank market (target rate).

Given the response of asset markets to QE, the former option poses the risk of asset market deflation and possible spillovers to the real economy. To clarify, these arguments suggest there are good reasons to keep reserves in chronic excess but does not imply the Fed should permanently adjust to a “floor” system.

The “platinum coin” has been shot down as a potential response to hitting the debt ceiling, but it has made a substantial impact in expanding debates about how our modern monetary system actually functions. One of these topics, the “permanent floor,” will likely remain a prominent topic of macroeconomic arguments for at least as long as the Fed operates monetary policy within that system. The fantastic recent discussion on this subject has vastly improved my understanding of the policy’s intricacies, but has not altered my initial impression about the future practice of monetary policy (emphasis added):

An “interest-on-reserves regime” appears likely to rule monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

Special thanks are owed to Tom Hickey (Mike Norman Economics) and Michael Sankowski (Monetary Realism) for posting links to this blog. For their contributions through comments, I would also like to thank Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax.

While continuing my own effort to further understanding of the permanent floor, related posts keep rolling in. Unfortunately my earlier post was remiss in recognizing contributions by Ashwin Parameswaran and Frances Coppola even prior to the outburst. A major player from the start, Steve Randy Waldman has once again raised the bar for a confederacy of dorks. David Beckworth, Peter Dorman, Nick Rowe and Stephen Williamson (see here, here, and here) also share their thoughts.

Once again, I won’t spend much time recapping the major points of contention. My intent is to highlight a few questions that came to mind while reading but, in my opinion, were not adequately addressed. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Question(s): What are the inflationary effects, if any, of the “platinum coin” both at and away from the zero lower bound (ZLB)? Under a “permanent floor” vs. “corridor” system?

Answer(s): As stated previously:

When the Treasury deposits a $1 trillion platinum coin at the Fed, the Fed credits the Treasury’s account with $1 trillion in reserves. These reserves, however, are not counted in the monetary base since the Treasury's account does not count as reserve balances in circulation. The simple action of depositing a platinum coin at the Fed therefore has no direct impact on the economy that would require sterilization*. In fact, the primary (sole?) purpose of this exchange is to allow the Treasury (Congress) to spend without requiring debt sales that would exceed the debt limit.

The platinum coin, in itself, is therefore not inflationary regardless of whether or not the economy is at the ZLB. The story, however, need not end there. Unburdened by the obligation to sell debt when deficit spending occurs, government deficit spending (up to the coin’s value) will directly increase the monetary base by adding reserves to the private banking system (reserves in circulation).

Operating within a “permanent floor” system, the Fed can maintain control of interest rates by paying a positive interest rate on reserves (IOR) AND elect whether or not to sterilize the monetary base expansion. If sterilized, the Fed could actually increase interest income in the private sector by selling assets with a higher yield. This would have an inflationary effect, though it may be offset by portfolio rebalancing. If left unsterilized, the monetary base expansion would likely generate asset price inflation and rising inflation expectations, at least in the short-run, given recent experiences with QE. In either case, the increase in deficit spending (otherwise not permitted by the debt limit) should ensure an overall inflationary bias.

Under the old monetary regime (pre-2008; “corridor” system), the Fed would probably sterilize the expansion by selling Treasuries (at least initially). Although the monetary base and interest rate are left unchanged, the deficit spending results in the private sector gaining net financial assets (NFAs; e.g. Treasuries). This is exactly the same result we see today! The only tweak is that the Fed, not Treasury, becomes the supplier of Treasuries.

Still under the old monetary regime, if left unsterilized, the expansion of the monetary base would push interest rates to the ZLB. The inflationary effects of the downward pressure on short-term rates depends on the time period in consideration (often short-term) and the degree of influence from several potential cross-currents (in no particular order):

1) Decreases interest income - deflationary

2) Weakens the currency - inflationary

3) Lowers debt service costs to borrowers - inflationary

4) Increases bank lending - inflationary

5) Raises inflation expectations - inflationary

The above list is in no way exhaustive, but does suggest an inflationary bias. Countering this view, Scott Sumner states:

higher interest rates are inflationary. They increase velocity. If you don’t believe me, check out interest rates and velocity during any extremely high inflation episode. When rates rise, inflation usually rises.

Perhaps surprisingly, I do believe that interest rates and velocity show a relatively strong correlation over time. What I disagree with is the direction of causation that Sumner ascribes to this relationship. From my perspective, decreasing velocity implies decelerating bank lending and/or declining inflation expectations. Witnessing either of these factors would encourage the Fed to lower interest rates, hence any causation runs in the opposite direction of Sumner’s claim. Determining whether interest rates or velocity tends to move first would be enlightening, if feasible, but for now I’ll conclude that lower interest rates are inflationary.

Under any of these circumstances, the transaction entailing a platinum coin between the Treasury and Fed, in and of itself, is not directly inflationary*. However, presuming the platinum coin is accompanied by greater deficit spending, some inflation will stem from the growth of private NFAs regardless of the monetary regime and sterilization decision. Corresponding monetary base expansion will also likely display an inflationary bias, unless the Fed elects to sterilize the expansion under the old “corridor” system. The platinum coin is therefore always inflationary.

Special thanks for their contributions through comments are still owed to Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax. Stay tuned for at least one more post in this series.

*it may indirectly impact the economy by altering expectations

Several months ago I wrote (emphasis added):

The Federal Reserve’s decision to implement an “interest-on-reserves regime” has clearly been beneficial in permitting the use of previously conventional measures for unconventional purposes, including the provision of liquidity and “financing” of federal budget deficits. Eliminating the payment of interest-on-reserves will not prevent the Fed from continuing to use open market operations in this manner, as long as the Fed Funds rate remains at zero. However, departing from this new regime will ensure that any future rate hikes be preempted by a reversal of the balance sheet expansion (or excess sale of Treasuries).

…

Given that any decision to cease paying interest-on-reserves would likely be temporary and the potential benefit is limited, there is seemingly little reason for the Fed to change course. An “interest-on-reserves regime” appears likely to rule monetary policy for the foreseeable future.

That prognostication, more recently made by Steve Randy Waldman, has generated an intense online debate about monetary operations, base money, the platinum coin and the so-called “permanent floor.” Waldman (also here and here) and Paul Krugman (see here and here) have been the major players, but others including Cullen Roche (see here and here), Scott Sumner (see here and here), Izabella Kaminska, Tim Duy (see here, here, and here), Merijn Knibbe, Ashwin Parameswaran, Greg Ip, and Scott Fullwiler (the foremost expert on the subject) have jumped in the ring. For monetary dorks/nerds, myself included, the discussion has been extremely interesting and illuminating.

Since so much has already been written on the matter, I won’t spend much time recapping the major points of contention. My intent is to highlight a few questions that came to mind while reading but, in my opinion, were not adequately addressed. Hopefully the answers put forth will shed light on areas of the debate that remain dark.

Question(s): Assuming a “platinum coin” example, Paul Krugman says:

“right now it makes no difference: financing the government by selling T-bills with zero yield, and financing it by making a deposit at the Fed, which either adds to the monetary base or sells some of its zero-yield assets, has, um, zero implication for anything except some peoples’ blood pressure.

But what happens if and when the economy recovers, and market interest rates rise off the floor?

There are several possibilities:

1. The Treasury redeems the coin, which it does by borrowing a trillion dollars.

2. The coin stays at the Fed, but the Fed sterilizes any impact on the economy, either by (a) selling off assets or (b) raising the interest rate it pays on bank reserves

3. The Fed simply expands the monetary base to match the value of the coin, an expansion that mainly ends up in the form of currency, without taking offsetting measures to sterilize the effect.”

First, does financing the deficit by making a deposit at the Fed add to the monetary base? Second, what impact on the economy does the coin have that requires ‘sterilizing’? Third, if the monetary base expands, will the expansion mainly end up in currency form?

Answer(s): When the Treasury deposits a $1 trillion platinum coin at the Fed, the Fed credits the Treasury’s account with $1 trillion in reserves. These reserves, however, are not counted in the monetary base since the Treasury's account does not count as reserve balances in circulation. The simple action of depositing a platinum coin at the Fed therefore has no direct impact on the economy that would require sterilization*. In fact, the primary (sole?) purpose of this exchange is to allow the Treasury (Congress) to spend without requiring debt sales that would exceed the debt limit. This seemingly harmless subversion of federal spending requirements actually holds great significance regarding the roles of private banking and the Fed in our current monetary system.

Free from the obligation to sell debt when deficit spending occurs, the Treasury would directly increase the monetary base as spending adds reserves to the private banking system (reserves in circulation). If the Fed was not operating under a “permanent floor” system or at the zero lower bound (ZLB), this would require the Fed to sterilize the effect either through asset sales or debt sales. Since the Fed would have reduced its balance sheet to pre-2008 levels, asset sales would be relatively limited in quantity. The Fed is also legally prohibited from selling its own debt, so it’s seemingly fortunate that the Fed has been permitted to issue time deposits since September 2010 (h/t jck in comments). Aside from the slightly altered roles in affecting the monetary base, it’s important to note that the Fed would become the primary payer of interest in this scenario. Although this has no impact on a consolidated government balance sheet (combining the Treasury and Fed), it would likely require the Fed to either indefinitely operate with negative equity or receive substantial transfers of capital from the Treasury (see forthcoming post on the logistics of Fed ‘insolvency’).

While the Fed’s role and independence is diminished by these actions, the role of private banks could potentially be reduced by far more. With government spending unconstrained by debt sales (and a compliant Fed), the government could subvert the reign of private banks as primary issuers of money. This would drastically reduce the profitability of banks and their power to influence government actions. Recognition of these potentially dramatic changes to the financial system may have provided the impetus for the Fed’s decision to shoot down the “platinum coin.”

Returning to Krugman’s third scenario and the third question mentioned above, let’s assume the Treasury increases the monetary base by spending reserves into the system and the Fed wishes to raise interest rates. If the Fed does not want to operate under a “permanent floor” system, then it must sterilize the monetary base expansion (or remain at the ZLB).

However, if the Fed elects to operate under a “permanent floor” system, then it can raise interest rates by raising the interest rate on reserves (IOR) AND decide whether or not to sterilize the increase in the monetary base. If the Fed chooses not to sterilize, the rising monetary base will consist of either non-interest bearing currency or interest-bearing reserves. Assuming that the expansion “ends up mainly in the form of currency” requires that banks (and individuals) either cannot exchange currency for reserves or prefer a non-interest bearing asset to an interest-bearing one. Since Waldman informs us that “holders of currency have the right to convert into Fed reserves at will (albeit with the unnecessary intermediation of the quasiprivate banking system)” and the latter constraint is irrational (certainly for large quantities), the expansion will almost certainly consist mainly of reserves.

As this post is already bordering on (crossed?) being of excessive length, the remaining questions and answers will be temporarily postponed. Special thanks for their contributions through comments are owed to Scott Fullwiler, JKH, RebelEconomist, Dan Kervick, Ashwin Parameswaran, wh10, Detroit Dan, K, JW Mason, jck and last, but not least, Mike Sax.

*it may indirectly impact the economy by altering expectations