Over the past few years it has become increasingly clear that the Federal Reserve and federal government are targeting rising asset prices, rather than incomes, as a way of generating economic growth. A recent post outlined some of the dangers of persistent negative real interest rates:

Households and businesses “with access to cheap borrowing” have been pouring money into stock, bond, housing and commodity markets rather than investing in tangible capital. The remarkable rise in asset prices has unfortunately not funneled down to households in the bottom four quintiles of income and wealth, only furthering the inequality gap.

Cullen Roche addressed a similar issue yesterday in a post on The Fed’s Disequilibrium Effect via Nominal Wealth Targets:

Fed policy and the monetarist perspective on much of this can be highly destabilizing by creating this sort of ponzi effect where asset prices don’t always reflect the fundamentals of the underlying corporations. It’s not a coincidence that we’ve have 30 years of this sort of policy and also experienced the two largest nominal wealth bubbles in American history during this period.

The title of this blog is also not a coincidence, since my formative years encompassed both the dot-com and housing bubbles. My relatively limited experience with financial markets and macroeconomics (based on age) has been punctuated by financial instability. These memories are the driving factor behind my desire to study financial instability and inform policy decisions that can stabilize the business cycle.

In a recent post on The Spinning Top Economy, Matthew Berg helps further my goal with insight on measuring financial instability (my emphasis):

Now we have Government IOUs on the bottom, serving as the base of the economy. Bank and Non-Bank IOUs are leveraged on top of those IOUs – somewhat precariously.

In fact, you can think of the economy as a spinning top rather than a pyramid. Like a spinning top, the more top-heavy the economy becomes, the greater its tendency to instability, and the more readily it will topple over and collapse in a financial crisis.

Now, what happens if, as was the case during the dot-com bubble and the housing bubble, private sector net financial assets go negative but net worth continues to grow?

In fact, the difference between the measures of net financial assets and net worth provides us with a good rule of thumb for how to spot a bubble economy. If private sector net worth is growing at a greater rate than private sector net financial assets are growing, then that means that the economy – symbolized by our spinning top – is growing more top-heavy.

So, what happens if we make the spinning top more top-heavy? You can go ask your nearest Kindergartener – it becomes more likely to topple over.

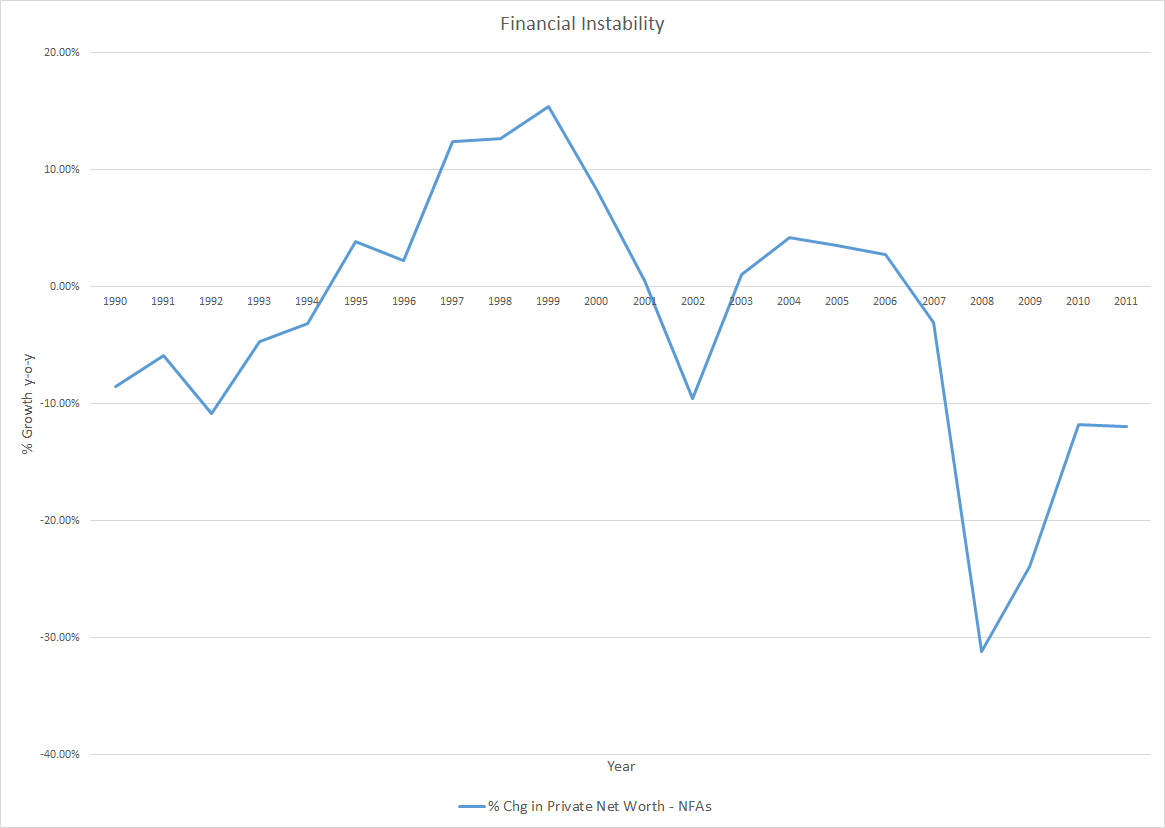

Since Matthew provides the guidelines for spotting “a bubble economy,” let’s take a look at the empirical data to see how well it aligns with the story. The first chart displays the growth rates of private sector net financial assets (NFAs) and private net worth over the past 20 years*:

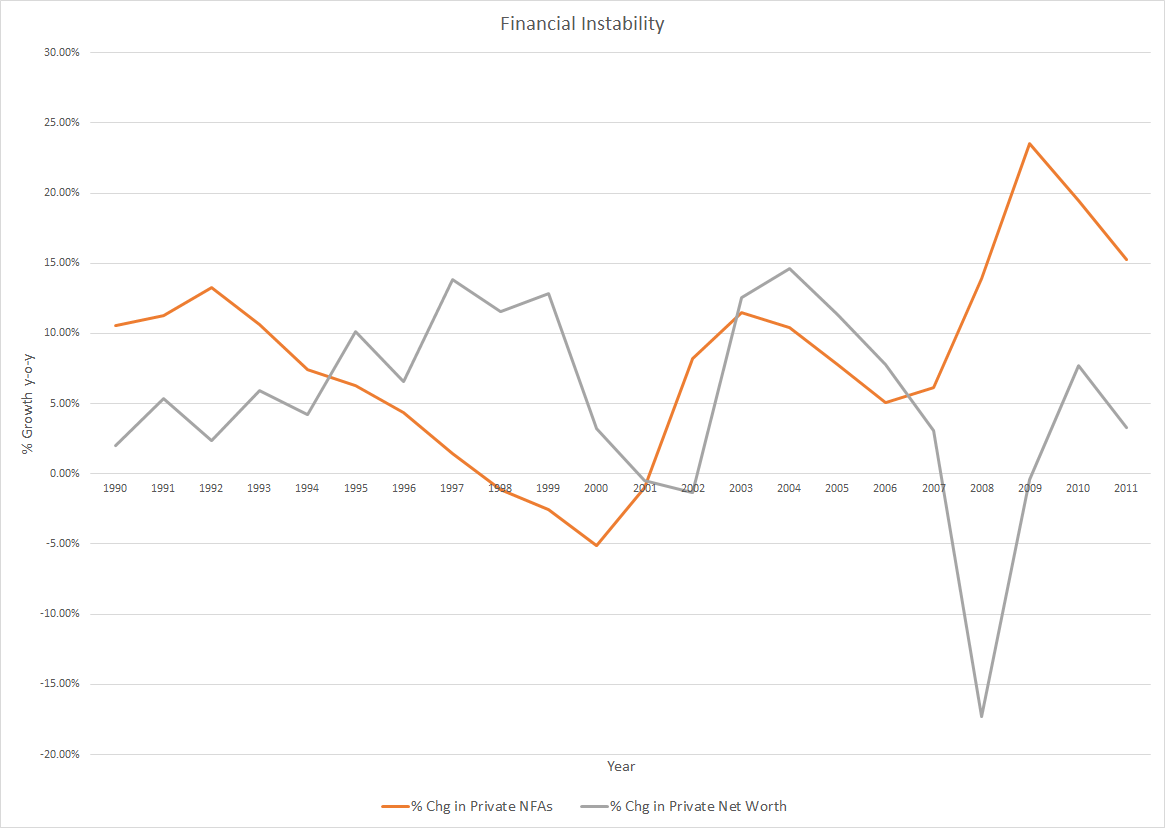

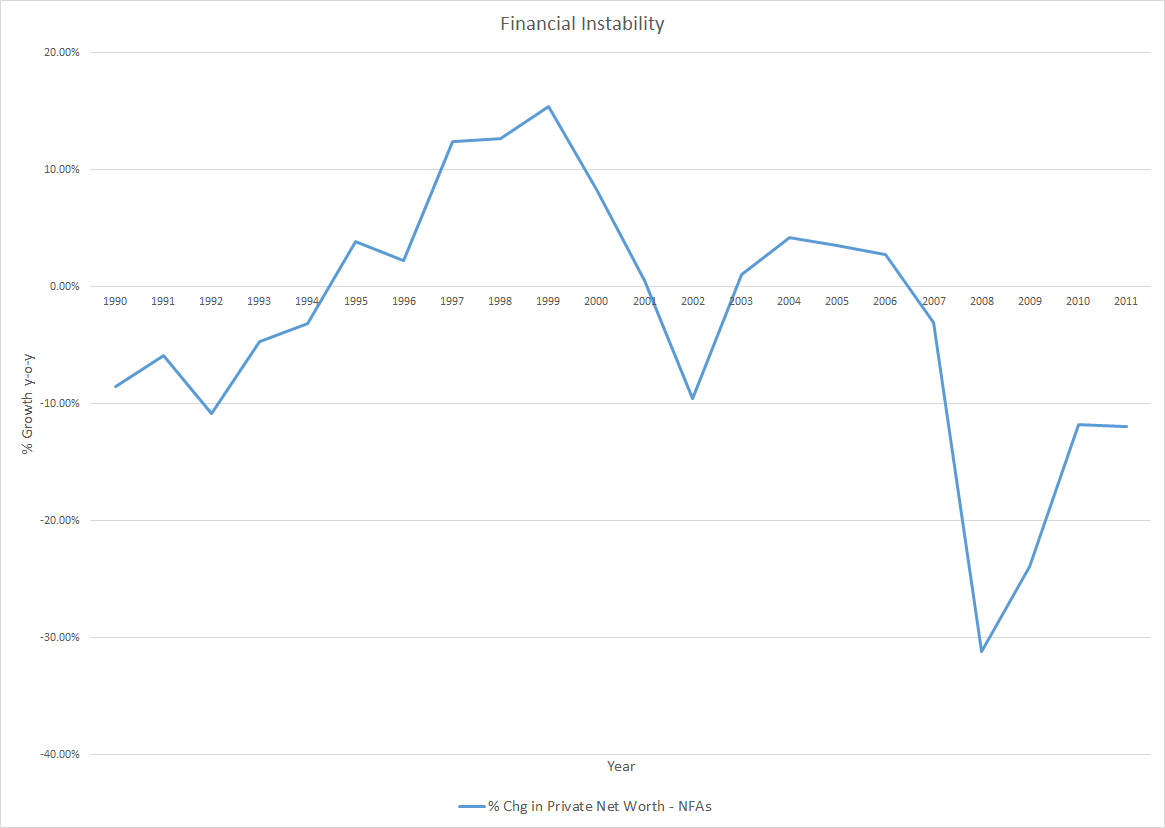

The negative growth rate in private NFAs corresponds with the Clinton surpluses, while the two positive surges are due to the Bush tax cuts and Bush/Obama stimulus measures. Turning to the growth in private net worth, the brief decline stems from the bursting dot-com bubble and the massive drop from cratering house prices. Combining the two measures will show when/if the economy was becoming “top-heavy” (first chart displays the past 50 years; second chart is the same data but only the past 20 years, for clarity):

Past 50 Years

Past 20 Years

Growth of private net worth began outpacing the growth of private NFAs in 1995 for the first time since 1979. The difference in growth rates then remained positive for 10 of the next 11 years. This streak is truly remarkable given that prior to 1995, the difference had only been positive in five other years dating back to 1961.** At the end of 2006, the U.S. economy was clearly more “top-heavy” than any previous time in the post-war era.

Over the past three decades, growth in private debt exceeding income and declining nominal interest rates have generated enormous returns for asset holders. Throughout the 1980’s and early 1990’s, federal deficits provided more than enough NFAs to keep pace with rising private net worth. Then, in 1995, deficits began decreasing just as the growth of net worth (and private debt-to-GDP) began accelerating higher. The unsurprising result has been more than a decade of meager asset returns, subpar economic growth and high unemployment.

The government policy of targeting nominal wealth, driven by an expansion of private debt, has failed not only at increasing net worth but also, and more importantly, at creating sustainable growth in output and employment. Going forward the focus of policy must return to promoting the growth of income and assets, which in turn will fuel higher output, employment and ultimately wealth.

*Data for private net worth comes from the Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds Accounts of the United States (Z.1). Data for private net financial assets (NFAs) comes from the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) at the BEA.

**Aside from 1979, growth of private net worth exceeded the growth of private NFAs in 1961, 1965, 1969 and 1978 (0.05%).

Related posts:

The Rise of Debt, Interest, and Inequality

Fear of Bubbles, Not Inflation, Returns to the Fed

Why the Federal Reserve Mandate Means That Bernanke Doesn't Have to Worry About Bubbles

More on the adaptive inflation expectations hypothesis by Robert @ Angry Bear

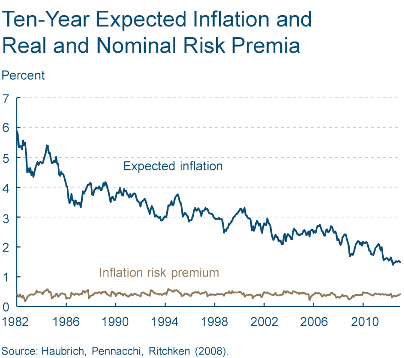

My claim is that expected inflation over the next 5 (and 10 and 20) years is very similar to actual inflation over the past year. I think the data generally fit the crudest most mechanical adaptive expectations hypothesis.

This would be interesting for two reasons.

First, the adaptive expectations hypothesis has been treated with utter contempt for roughly 4 decades. It is considered an example of the sort of thing which economists must utterly reject. The effort to replace it has lead to a lot of mildly interesting math and highly implausible assumptions.

Second, there is a huge and very vigorous discussion of forward guidance by the Fed Open Market (FOMC) Committee. It has been argued that even when the Federal Funds rate is essentially zero, the FOMC can stimulate the economy by causing higher expected inflation. It is generally agreed that the FOMC has been convinced by this argument. I think this implies that there should be anonalous increases in expected inflation on the dates when the FOMC began to try to cause higher expected inflation -- roughly the announcements of QE 1-4, operation twist and of forward guidance of how long it will keep the Federal Funds rate extremely low. An excellent fit of expected inflation using only lagged inflation creates serious difficulty for those who think the FOMC always could and finally has promoted higher expected inflation.

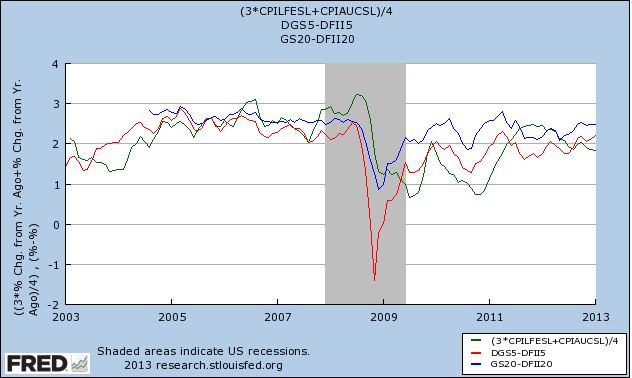

Woj’s Thoughts - This topic is reminiscent of a chain of posts nearly six months ago that began with JW Mason’s inquiry, Does the Fed Control Interest Rates? Jazzbumpa and Art Shipman chimed in with their own opinions, the latter providing this relevant chart on the path of interest rates over time:

Responding to the others’, my view was that:

market expectations of future Fed action are sticky. During the post-war period until about 1980, inflation was consistently rising despite mainstream economic views that suggested those conditions would not persist. Following a lengthy inter-war period of near rock-bottom interest rates, market participants were slow to adjust expectations to the actual height of interest rates that would occur before sustained disinflation began. Once disinflation began in the early 1980’s, market expectations were equally slow in recognizing how long disinflation could persist and therefore how low the Fed would ultimately take rates (and hold at zero).

Returning to Robert’s claim, I suspect the recent strong correlation between the previous year’s actual inflation and inflation expectations for the next 5 or 20 years is partially due to the lengthy period of low inflation that came prior. In other words, if inflation were to start trending higher or lower over an elongated period, I predict inflation expectations would lag actual inflation while moving in the same direction. The adaptive inflation expectations hypothesis will therefore still hold, only more years of recent data will need to be incorporated into expectations formation. Validation of this hypothesis will deal a serious blow to the perception that Fed communications at the ZLB are an effective form of stimulus.

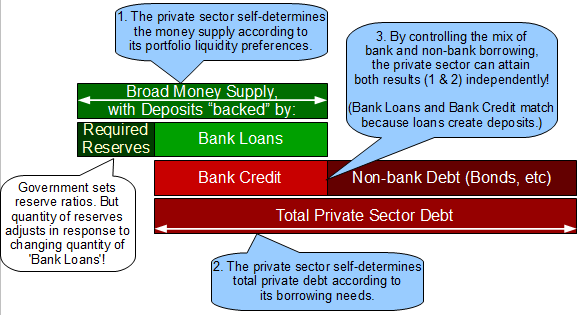

...is from Warren Mosler’s Soft Currency Economics II (Modern Monetary Theory):

the Fed must provide enough reserves to meet the known requirements, either through open market operations or through the discount window. If banks were left on their own to obtain more reserves no amount of interbank lending would be able to create the necessary reserves. Interbank lending changes the location of the reserves but the amount of reserves in the entire banking system remains the same. For example, suppose the total reserve requirement for the banking system was $ 60 billion at the close of business today but only $ 55 billion of reserves were held by the entire banking system. Unless the Fed provides the additional $ 5 billion in reserves, at least one bank will fail to meet its reserve requirement. The Federal Reserve is, and can only be, the follower, not the leader when it adjusts reserve balances in the banking system.

Bibliography

Mosler, Warren (2012-10-25). Soft Currency Economics II (Modern Monetary Theory) (Kindle Locations 367-373). . Kindle Edition.

Earlier this week I discussed the dangers of misunderstanding “helicopter money” and higher inflation targets. A focus of that post was the incentives stemming from negative real interest rates that will lead to greater investment in real assets, not businesses. The obvious implication is that negative real interest rates entail significant risk of spurring asset bubbles.

This discussion of asset bubbles comes on the heels of St. Louis Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein’s speech that suggested the Fed was becoming increasingly concerned about bubbles, not inflation. According to a recent Bloomberg article, apparently Fed Chairman Bernanke was not onboard with the supposed shift (h/t Tim Duy):

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke minimized concerns that the central bank’s easy monetary policy has spawned economically-risky asset bubbles in comments at a meeting with dealers and investors this month, according to three people with knowledge of the discussions.

Do Bernanke’s comments imply the change Stein alluded to is not really happening? Not necessarily. To understand why, one must consider the goals assigned to Bernanke or any Fed Chairman for that matter. The following is from Chapter 2 of the Federal Reserve System’s own publication, Purposes & Functions:

The goals of monetary policy are spelled out in the Federal Reserve Act, which specifies that the Board of Governors and the Federal Open Market Committee should seek “to promote effectively the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.”

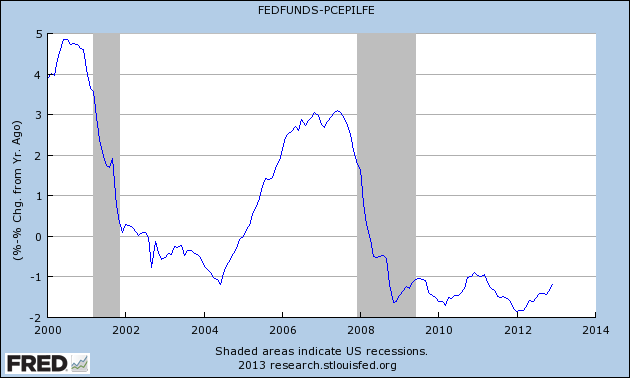

Although no explicit mention of preventing asset bubbles is made, the goal of stable prices leaves the door open for such an interpretation. Before addressing the Fed’s own interpretation of stable prices, its worth discussing the specific types of assets that are seemingly most prone to bubbles. The three major categories are commodities (e.g. oil, copper, sugar), financial assets (e.g. stocks and bonds), and housing. During the past decade real interest rates have actually been negative more often than not (Real Interest Rate = Effective Fed Funds rate - core PCE):

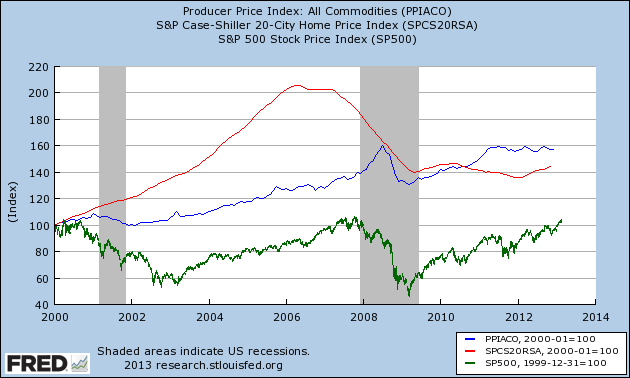

Unsurprisingly the past decade has also witnessed asset bubbles in commodities, stocks and housing:

Prices of these assets have clearly been anything but stable. So has the Fed failed in that aspect of its mandate? The answer is a resounding “NO.”

To remedy the cognitive dissonance readers may be experiencing, consider how the aforementioned real assets affect the FOMC’s preferred inflation measure, core Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). Financial assets are noteworthy in their distinct omission from the type of products making up PCE. Commodities are included in the general price measure, however core PCE is calculated by excluding a couple of the more volatile commodity components: food and energy. Housing is actually included in core PCE but is calculated using the space rent of nonfarm owner-occupied homes, not actual house prices. Focusing on core PCE thereby removes any direct concern with asset bubbles.

Bernanke has already announced his plans to step down as Fed Chairman early next year (2014). Given the Fed’s stated mandate and preferred measure of prices, it is no wonder that Bernanke is unconcerned with asset bubbles. The goals of his chair are to maximize employment and maintain stable prices. Since the types of assets prone to bubbling are not included in core PCE and appear relatively uncorrelated with that measure, to the degree that bubbles can benefit employment in the short run, they may actually be desirable.*

These institutional incentives of a Fed Chairman are unfortunately at odds with the country’s longer term economic goals. Asset bubbles created by excessive lending and/or negative real interest rates are always followed by busts. These busts are simply the recognition of malinvestment that already took place during the boom. If the booms are financed with significant leverage, the resulting deleveraging may lead to a debt deflationary spiral. Whether or not that’s the case, though it usually is, malinvestment suppresses both employment and economic growth over time.

One can argue over whether Bernanke’s views on the effectiveness of monetary policy are correct or not, but his decision to ignore asset bubbles is perfectly rational given the circumstances. Shifting the Fed’s focus from inflation to bubbles will therefore require changing the institutional incentives.

*The three major asset categories mentioned above presumably will have very different effects on employment. Among the three, commodity bubbles are least desirable from an employment perspective. Higher commodity prices generally hurt consumer spending, which may lead to a temporary decline in employment. Housing bubbles are the most desirable in these terms since the increased demand can generate a temporary employment boom in construction and housing-related services.

Rational nerdiness vs macho bada$$ery in monetary policy by Cardiff Garcia @ FT Alphaville

The US economy has had several false starts since 2009, and it’s likely that several tangled factors were responsible for their not lasting longer. It’s reasonable to think that one of these factors was that the initial reflationary effects of these unconventional measures faded, because of doubts about the Fed’s commitment to maintaining accomodative policy during a period of catch-up growth. If such growth threatened to generate above-target inflation, then monetary conditions could be expected to tighten.

The rational-nerdy thing to do was to soften the macho commitment to inflation and commit to a temporary period of inflation-tolerance, thereby balancing the two sides of the mandate — but to do so while retaining credibility on both. But as Harless notes, ceding a little ground on one side could be interpreted as ceding all ground. Being a “macho badass” central banker means credibly committing to never cede ground.

…

All of which has been a long windup to saying that the appeal of the Evans Rule, and if we ever get it, some variation of NGDP level targeting, is this: they institutionalise the macho badassery, which in a dual-mandate framework can only be applied to one of the two mandates.

Woj’s Thoughts - This post is reminiscent of a thread from last year involving Steve Roth and Ryan Avent on The Asymmetric Nature of Monetary Policy. In that post I made the following claim:

Whereas Roth suggests that asymmetric credibility stems from the Fed’s actions, I believe it is actually an inherent condition in our current monetary system. The Fed sets the base price for money and credit, but with private banks free to create credit, it holds relatively little control over the total amount outstanding at any time. As growth in the US has exceeded inflation for much of the past three decades, the conditions were ripe for borrowing and credit outstanding now greatly surpasses the sum of base money.

Even if the Fed promised indefinite QE, it’s hard to see the mechanism, aside from adjusting inflation expectations (wealth effects are minimal), by which this would spur real growth. Given the Fed’s skewed abilities and determination to maintain its credibility, it seems more obvious why inflation targeting remains prominent. Further, this may help explain why the Fed downplays its employment mandate (which should be removed anyways). Facing the endgame, the Fed knows it can reduce inflation (and growth) but remains unsure how successful it could be at achieving other targets.

Sucumbing to pressure, the Fed has finally decided to cede ground on its commitment to inflation. Unfortunately for the Fed, both inflation expectations and unemployment are not cooperating:

At this point I doubt whether even altering inflation expectations would provide any boost to actual inflation or employment. If fiscal policy continues to contract the budget deficit, these numbers will continue moving in the wrong direction. The Fed has taken a big risk with its established credibility. I fear the results will be very disappointing.

Last year I took a chance and threw my own projections into the ring. Similar to Byron Wien and Edward Harrison, I mostly selected events that were widely seen as having a low probability (less than 33%) but which I believed held a greater than 50% chance of occurring. The final results were a bit disappointing, but that won’t stop me from trying again this year. Since these predictions already represent a late release, without further adieu, here are the 2013 predictions:

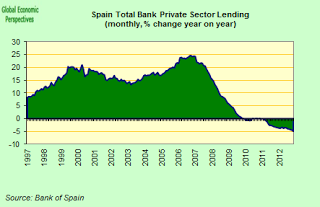

1) Spain requests access to ECB’s OMT - Since ECB President Mario Draghi announced the OMT program, yields on Spanish debt have fallen rather dramatically. Although this eases financing pressure, it has done little to alter the actual economy’s downward spiral. During 2012 Spain’s GDP growth became increasingly negative, falling by 1.8% year-on-year in the fourth quarter. Meanwhile unemployment continues its meteoric rise to over 26% for the general population and nearly 60% for youth. With the large banks still severely undercapitalized and households over-indebted, private sector lending continues to decline:

Seeing no recovery and potentially a worsening decline, “bond vigilantes” will eventually test Draghi’s threat. At that point Spain will be forced to accept a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in return for ECB bond-buying through the OMT program.

2) The Euro finishes the year above $1.30 - After falling nearly 10% during the first half of 2012, the euro has more than recouped its losses on the back of optimism and deflationary policies.

At points during 2013 the optimism is likely to fade, but I expect politicians and central bankers will take the necessary steps to quell fears for the time being. Unfortunately those steps will involve further deflationary policies that push the euro higher. These competing forces will largely cancel out, leaving the euro close to or above where it began the year.

3) The Eurozone remains in recession the entire year - Forecasters now expect euro-zone economic activity to be flat this year, down from a previous prediction of 0.3% growth made just three months ago. Last year saw practically continuous downgrades to GDP growth forecasts and I expect this year to be no different. Austerity measures are momentarily easing, but more will likely be enacted based on the outcomes of several elections. The recent appreciation of the euro against several major currencies will also dampen growth by putting pressure on net exports. With banks across Europe trying to build up capital and persistently high unemployment, the private sector will remain especially weak. Though Germany may experience a temporary rebound, the Eurozone as a whole will not register GDP growth this year.

4) The Japanese yen rises above 90 per $ - Since the election of PM Shinzo Abe, the yen has fallen fast and is down more than 20% from recent highs.

During this time the Nikkei has risen more than 20%, yet yields on Japanese sovereign debt are little changed. This suggests many foreigners may be speculating on the supposedly forthcoming monetary and fiscal stimulus. As previously stated, the fiscal stimulus will probably be small and short-term. On the monetary front, short of actually entering the foreign exchange market, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) has essentially no mechanism to spur inflation and thereby cause a sustained depreciation of the yen. When market participants recognize the inability of Japan to avoid continued deflation, the yen will return to appreciating against the dollar.

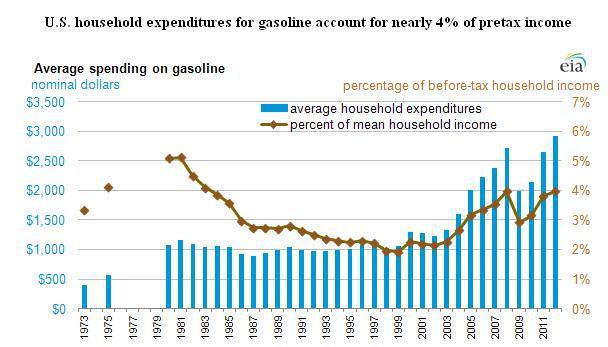

5) Gas prices will peak above $4.20 per gallon and set a new yearly record-high average above $3.75 per gallon - Gasoline prices have been on the rise for the past 31 days, currently averaging approximately $3.75 per gallon. Though this current streak will probably end soon, prices are unlikely to give back much of the gains before beginning the typical rise into summer. The ongoing potential for flare ups in the Middle East will keep prices elevated throughout the year. Higher gas prices, which already account for 4% of before-tax household income (chart below), will be a drag on consumer spending in 2013.

6) U.S. Yearly GDP growth falls below 1.5% - Forecasts of ~3% annual GDP growth over the past couple years have been overly optimistic as real growth in 2011 and 2012 was merely 1.6% and 1.9%, respectively. Apparently forecasters are being a bit tamer in their estimates this year, now expecting only 2% annual growth. Unfortunately I suspect these estimates will once again prove too optimistic. Various tax hikes and the upcoming sequester (which will go through in some respect) will reduce the budget deficit by a few percent this year. Housing is likely to remain a bright spot, but further declines in interest rates will not lead to similar magnitudes of the wealth effect. Credit remains tight for many households and small business, which should also limit private sector activity. All of these factors combined will probably not be enough to bring about a new recession but will lead to the lowest annual growth rate during this upswing.

7) U.S. Unemployment rises above 8% - Currently sitting at 7.9%, the unemployment rate is forecast to decline during 2013. Due to weaker GDP growth, corporate revenues will barely rise again this year. As companies face increasing pressure to maintain profit margins at record levels, a new wave of layoffs may occur. Separately, continuing economic growth will encourage previously discouraged workers to re-enter the job market. Both of these factors will lead to slightly higher measured unemployment.

8) Federal Reserve forecasts shift first rate hike to 2016 - After extending their forecast for the first rate hike to 2015, the Federal Reserve changed its tactics to a more rule-based monetary policy. The Fed has, in effect, promised to keep rates low until we've hit either 6.5 percent unemployment or 2.5 percent inflation. Based on the above outlook for unemployment and a continuing decline in inflation expectations (chart below), FOMC members will revise their own forecasts and push back expectations for the first rate hike.

9) U.S. Corporate Earnings (ex-Federal Reserve) finish year below 2012 peak - Meager revenue growth was not enough to prevent U.S. Corporate Profits after tax from reaching record highs in the fourth quarter of 2012 on the back of record profit margins.  As global growth slows in 2013, revenues will come under further pressure. At this point the ability of firms to continue cutting costs without sacrificing output seems limited, which means margins may begin to compress. As margins revert to previous norms, earnings will register a yearly decline.

As global growth slows in 2013, revenues will come under further pressure. At this point the ability of firms to continue cutting costs without sacrificing output seems limited, which means margins may begin to compress. As margins revert to previous norms, earnings will register a yearly decline.

10) Bonds outperform stocks - During the first seven weeks of this year the stock market has been on fire, even though earnings estimates continue to fall.

Multiple expansion is currently being driven by the Federal Reserve’s actions despite their ineffectiveness at generating actual NGDP growth. When investors eventually turn their attention to continuing troubles in Europe, ongoing deflation in Japan, and/or weakening growth in China, U.S. earnings may once again enter the picture. Recognition that S&P 500 earnings growth has slowed substantially may cause the market to give up much of this year’s gain. These concerns combined with declining inflation expectations will result in many investors returning to the safety of U.S. Treasuries. The subsequent rise in prices (decline in rates) will generate another year of positive returns for the Treasury market.

Will my predictions prove too pessimistic once again? Only time will tell...

The Myth Of The Money Multiplier by Barkley Rosser @ EconoSpeak

That Fed control over the money supply has become a phantom has been quite clear since the Minsky moment in 2008, with the Fed massively expanding its balance sheet without much resulting increase in measured money supply. This of course has made a hash of all the people ranting about the Fed "printing money," which presumably will lead to hyperinflation any minute (eeek!). But the deeper story that some of us were unaware of is that apparently this disjuncture happened a long time ago. Even so, one of our number pointed out that official Fed literature and even many Fed employees still sell the reserve base story tied to a money multiplier to the public, just as one continues to find it in the textbooks, But apparently most of them know better, and the money multiplier became a myth a long time ago.

Woj’s Thoughts - Rosser refers to a paper from the Federal Reserve Board’s Finance and Economics Discussion Series that was the source of a recent Quote of the Week:

“Money, Reserves, and the Transmission of Monetary Policy: Does the Money Multiplier Exist?” (by Seth B. Carpenter and Selva Demiralp, May 2010):

Changes in reserves are unrelated to changes in lending, and open market operations do not have a direct impact on lending. We conclude that the textbook treatment of money in the transmission mechanism can be rejected.

As I noted in that post:

If staff members at the Federal Reserve are aware of the money multiplier myth than surely Bernanke and the other board members have heard the arguments. Unfortunately most mainstream economists, especially monetarists, continue to promote monetary stimulus as if the old regime still persists.

Fortunately the economics professors at James Madison stumbled across this paper and were convinced of its conclusion. Hopefully they will join a minority of current economists in training future economists to recognize the money multiplier does not exist.

Related posts:

Fullwiler - "The main shortcoming of the money multiplier paradigm"

IOR Killed the Money Multiplier

Fighting for Endogenous Money on Two Fronts

The Federal Reserve Will Need A 'Fairy Tale Ending' To Unwind Its Balance Sheet by Peter Tchir @ Money Game

I don’t see how the Fed announces anything that talks about taking down the balance sheet. Not now, and possibly not ever. The moment people get concerned, the market will start pricing in the unwind, no one will want to buy the long end of the curve and it will play havoc with rates.

Who in their right mind would buy 10 year treasuries when you know that the equivalent of multiple years of supply is being sold by the Fed along with the ones the Treasury department will need to sell. It isn’t like the Treasury department will be able to stop issuing bonds. They have to deal with rolls and frankly with ongoing deficits.

As a hedge fund, are you really going to “fight the fed” and buy 10 year bonds once you think they need to sell them? I don’t think so. More importantly, who will make a nice 10 year mortgage when the 10 year treasury is selling off?

That is the problem. The Fed has built up such a large portfolio, that the only likely way to exit it is through letting it mature. That at least takes the $2 trillion seller out of the market (remember, they are still in buying mode).

Due to the potential damage a sell off occurs, both in the cost of funds for the treasury, but more importantly in the knock on effect it has on other yield products, I would expect the Fed to defend any big move aggressively. Not only do they have the money to do it, but the float is small enough it may take far less than people think to defend the market.

Woj’s Thoughts - Six months ago I argued that an "Interest-On-Reserves Regime" Will Rule Monetary Policy For The Foreseeable Future because:

departing from this new regime will ensure that any future rate hikes be preempted by a reversal of the balance sheet expansion (or excess sale of Treasuries). Balance sheet contraction, through open market operations, could very well depress asset values and raise long-term interest rates. If this occurs, the Fed would be effectively causing a new crisis just as the economy is becoming increasingly stable.

Tchir’s post breaks down the Federal Reserve’s current Treasury holdings, which amount to approximately 40 percent of outstanding supply in the 5 to 30 year maturity range. With the Federal Reserve now purchasing $45 billion of Treasuries per month, those percentages are set to grow rapidly in the coming year(s). Given the potential fallout from even signaling an end to current rounds of QE, I fail to see why future FOMC members would take the risk of actively reducing the monetary base when other options exists. This outlook for monetary policy is precisely why it’s so important to further understanding of the Permanent Floor.

St. Louis Federal Reserve Governor Jeremy Stein recently gave a speech titled "Overheating in Credit Markets: Origins, Measurement, and Policy Responses."

Carola Binder was struck by the historical relevance of the chosen terminology and offered the following comment in a post on Overheating and the Fed:

In the New York Times, Binyamin Applebaum writes that Stein's speech "underscored that the Fed increasingly regards bubbles, rather than inflation, as the most likely negative consequence of its efforts to reduce unemployment by stimulating growth." In fact, the Fed's concern about bubbles is not so new. After the Great Depression, it was widely believed that the stock market overheated in the 1920s, leading to the Great Crash in 1929 and the onset of the Depression. In those days, the word for bubbles or overheating was speculation, and it became a dirty word indeed. After the Great Depression, speculation remained a major concern of the Fed. The Fed very explicitly regarded bubbles as the most likely negative consequence of its efforts to reduce unemployment by stimulating growth.

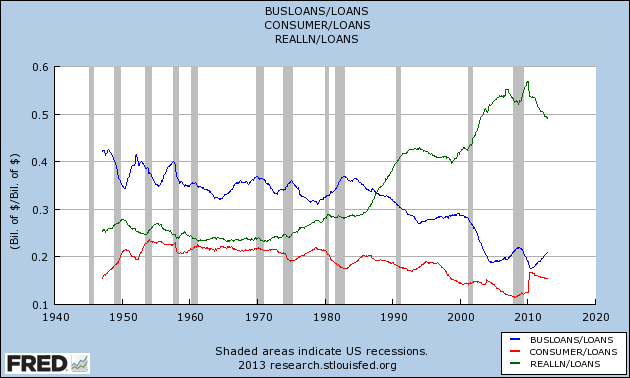

Apparently the Fed has come full circle. Carola goes on to provide a couple excerpts from FOMC minutes during the 1950’s, the last time the Federal Reserve was concerned with asset bubbles instead of inflation. The subsequent change in thought is not overly surprising given that stock markets flatlined starting in the mid-1960’s, as inflation picked up and became a major cause for concern throughout the 1970’s. What is disturbing, is the Federal Reserve’s failure to recognize the changing landscape over the past three decades.

During that time, commercial bank lending has largely shifted its priorities from financing tangible (capital) investment through business loans to financing the purchase of already existing assets (e.g. houses, stocks and bonds):

(BUSLOANS = Commercial and Industrial Loans; REALLN = Real Estate Loans; LOANS = Loans and Leases at All Commercial Banks)

It should therefore come as no surprise that the transmission mechanism of monetary policy is now primarily through various asset markets (i.e. real estate monetary standard).

Consider the following charts showing various asset prices and inflation rates during the past 30 years:

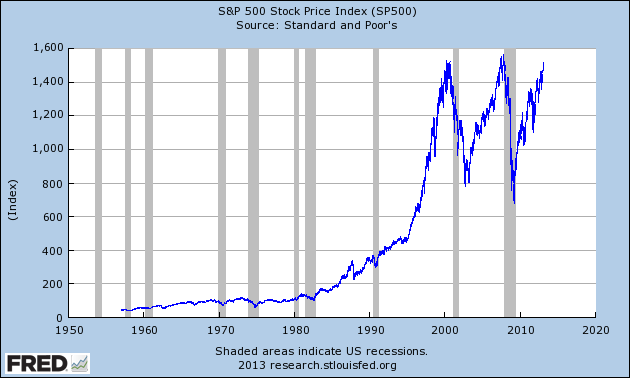

Stocks:

High-Yield Corporate Debt:

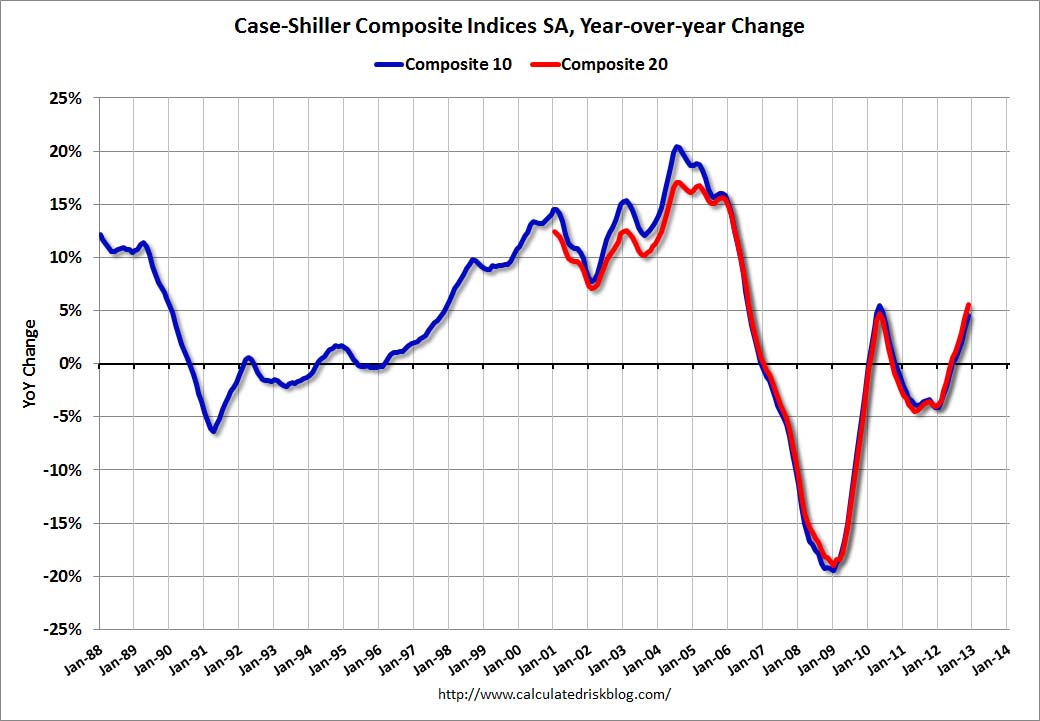

Houses:

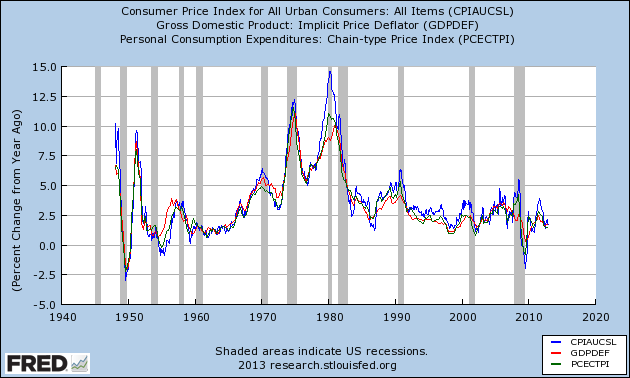

Inflation:

Over the past few years I’ve been very critical of the Federal Reserve’s actions spanning the last couple decades. One of the primary reasons behind this view was the incessant focus on limiting inflation and utter lack of concern regarding asset bubbles. The present risk of a zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) and QEternity lies mainly in inflating new asset bubbles, not creating excessive measured inflation. If the Fed has finally come back around to this realization, that would certainly be a big step in the right direction.

The beginning of a new year is apparently as good a time as any to start thinking about buying a new home. At the start of 2012 I found myself frequently engaged in discussions about whether or not it was finally the “right” time to buy a house. Mortgages with 30-year fixed rates were being offered around 4% and prices appeared to be stabilizing. Despite the widespread optimism, my conclusion was:

When deciding whether or not to purchase a home, there are certainly a whole host of factors to consider that were not discussed here (family, job security, income, savings/debt, location, etc). The purpose is to provide an alternative perspective to the seemingly common perception that now is the best time to buy and those who fail to act will miss a great opportunity. While I don’t rule out that possibility, I believe the outlook for home prices and mortgage rates suggests this window of opportunity will remain open for a few years. In fact, those who wait may be rewarded with lower mortgage rates and more house for their money. There is no rush to buy a home!

Now with the benefit of hindsight, my judgment appears to have held up relatively well. Although house prices have risen approximately 6 percent in the past year:

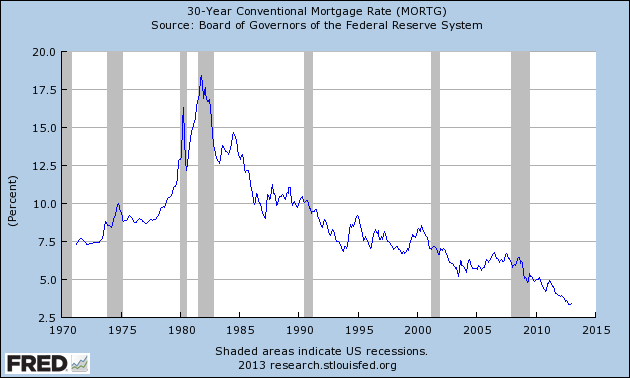

30-year fixed rate mortgages touched a new low of 3.3%: With 2013 only a month old, conversation among friends and family about buying new homes has picked up once again. Oddly enough, the substantial rise in prices over the past year is stoking demand for housing. (I say oddly because basic economics suggests demand should decrease when prices rise) However, before offering my views on future house prices, let me say a few words about mortgage rates.

With 2013 only a month old, conversation among friends and family about buying new homes has picked up once again. Oddly enough, the substantial rise in prices over the past year is stoking demand for housing. (I say oddly because basic economics suggests demand should decrease when prices rise) However, before offering my views on future house prices, let me say a few words about mortgage rates.

Over the past few months the FOMC has initiated QE3 (QEternity) and QE4, which involves purchasing $40 billion of Agency-MBS and $45 billion of Treasuries per month. Despite jubilant asset markets, inflation (core-PCE) and GDP growth remain well below 2 percent. This failure to stimulate real growth will likely lead the FOMC to extend its pledge of maintaining interest rates near 0 until at least 2016. Based on this combination of QE, ZIRP, low inflation, and stagnating growth, the chances of mortgage rates rising back above 4 percent anytime soon seems very limited.

Returning to the future direction of house prices, I remain skeptical that household balance sheets have been sufficiently repaired to permit a new debt-led boom. One of the better resources for housing market insights, Dr. Housing Bubble has highlighted the recent surge in investment demand. Meanwhile, Diana Olick discusses reports that Americans are tapping their homes for cash again. Clearly aspects of the previous bubble are returning, which makes it tough to rule out further gains in the short-term. That being said, US residential real estate just isn’t a great investment in real terms and here is Robert Shiller explaining why:

“Housing is traditionally is not viewed as a great investment. It takes maintenance, it depreciates, it goes out of style. All of those are problems. And there’s technical progress in housing. So, the new ones are better….So, why was it considered an investment? That was a fad. That was an idea that took hold in the early 2000′s. And I don’t expect it to come back. Not with the same force. So people might just decide, ‘yeah, I’ll diversify my portfolio. I’ll live in a rental.’ That is a very sensible thing for many people to do.

…From 1890 to 1990 the appreciation in US housing was just about zero. That amazes people, but it shouldn’t be so amazing because the cost of construction and labor has been going down.

…They’re not really an investment vehicle unless you want it for your personal reasons.”

If you want more proof, here is the chart Shiller is referencing:

My recommendation therefore remains basically the same as last year. Housing prices and mortgage rates may have bottomed, but the odds of either rising substantially in the next couple years remains small. Ultimately you should buy a house that you want to live in, not that you hope will be a good investment. If you plan on buying, just remember, there is no rush to buy a home!