1) Hit the “Defer” Button, Thanks… by David Merkel @ The Aleph Blog

This is why I believe that the biggest issue in restoring prosperity globally, is finding ways to have creditors and stressed debtors settle for less than par on debts owed. Move back to more of an equity culture from what has become a debt culture. A key aspect of that would be making interest paid non-tax-deductible for corporations, housing, etc., while making dividend payments similar to REITs, while not requiring payouts equal to 90% of taxable income. Maybe a floor of 50% would work, with the simplifying idea that companies get taxed on their GAAP income — no separate tax income base. Would certainly reduce the games that get played.

Anyway, those are my opinions. The world yearns for debt relief, but governments and central banks argue with that, and in the short-run try to paper over gaps with additional short-term debt that they think they can roll over forever. They just keep trying to hit the “defer” button, avoiding any significant reforms, in an effort to preserve the “status quo.”

Woj’s Thoughts - After reviewing the results of my 2012 predictions, I mentioned:

My main takeaway is that politicians are far more determined to maintain the status quo than I had expected. The underlying economic (and social) problems have once again been kicked down the road for future governments to handle.

Although David’s policy recommendations are becoming increasingly pervasive, they unfortunately remain nowhere near the level necessary for governments to test uncharted waters.

2) Can Germans become Greeks? by Dirk @ econoblog101

The ECB as well as other policy makers and politicians do not understand economics. They think that a simple recipe like “decrease government spending, export more” is enough to solve the euro zone crisis. The increase in government debt is a symptom of the crisis, not a cause. The cause of rising government debt was negative economic growth and bank bail-outs. These are the two problems which must be tackled. They are intertwined, so solutions should address both. Households cannot pay their mortgages in Spain and Ireland at the existing unemployment levels, and that is due to a lack of demand as households consume less and save more. This downward spiral must be stopped and turned around, since at negative growth rates even a government debt of €1 is too high.

It seems that instead of Greeks becoming Germans now the German are becoming Greeks. That means that without government spending Germany will not have positive growth rates. While this will come as a surprise to many, it shouldn’t be.

Woj’s Thoughts - Germany managed to run a slight fiscal surplus during 2012 that ultimately came at the expense of growth. In the fourth quarter, German GDP shrank by 0.5 percent. Meanwhile, attempts at structural reform (i.e. fiscal consolidation) in the European periphery appear to be speeding up the rise in unemployment and decline in growth. This dynamic is neither economically or socially sustainable, therefore the governments and ECB must either substantially change the current course or wait for countries to eventually exit the Eurozone.

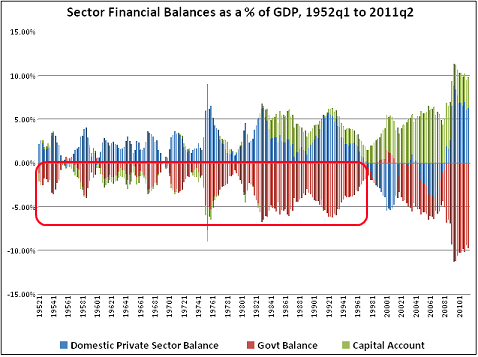

3) Did We Have a Crisis Because Deficits Were Too Small? by JW Mason @ The Slack Wire

The logic is very clear and, to me at least, compelling: For a variety of reasons (including but not limited to reserve accumulation by developing-country central banks) there was an increase in demand for safe, liquid assets, the private supply of which is generally inelastic. The excess demand pushed up the price of the existing stock of safe assets (especially Treasuries), and increased pressure to develop substitutes. (This went beyond the usual pressure to develop new methods of producing any good with a rising price, since a number of financial actors have some minimum yield -- i.e. maximum price -- of safe assets as a condition of their continued existence.) Mortgage-backed securities were thought to be such substitutes. Once the technology of securitization was developed, you also had a rise in mortgage lending and the supply of MBSs continued growing under its own momentum; but in this story, the original impetus came unequivocally from the demand for substitutes for scarce government debt. It's very hard to avoid the conclusion that if the US government had only issued more debt in the decade before the crisis, the housing bubble and subsequent crash would have been much milder.

Woj’s Thoughts - The scenario laid out by JW sounds equally plausible and compelling to me. Changes in tax policies during the 1980’s and 1990’s set the stage for massive increases in real estate loans and the corresponding housing price boom. Then the unmet demand for safe-liquid assets prompted both the rise of shadow banking and the dispersion of U.S. housing assets to the rest of the world. So as the last sentence attempts to make clear, the “crash would have been much milder” but a similar crisis would likely have occurred.

1) China after the Global Minotaur by Yanis Varoufakis

In the book’s penultimate chapter, I discussed the Soaring Dragon which, as everyone tells us, is waiting in the wings, purportedly to take over from the Global Minotaur (click here for a pdf copy of that chapter). In my concluding remarks, written back in January 2011, I wrote: “To buy time, the Chinese government is stimulating its growing economy and keeps it shielded from currency revaluations, in the hope that vibrant growth can continue. But they see the omens. And they are not good. On the one hand, China’s consumption-to-GDP ratio is falling; a sure sign that the domestic market cannot generate enough demand for China’s gigantic factories. On the other hand, their fiscal injections are causing real estate bubbles. If these are unchecked, they may burst and thus cause a catastrophic domestic unwinding. But how do you deflate a bubble without choking off growth? That was the multi-trillion dollar question that Alan Greenspan failed to answer. It is not clear that the Chinese authorities can.”

In the eighteen months that followed since those lines were written, events have confirmed the projected pattern. The table below reveals that the falling rate of Chinese consumption is continuing unabated. In 2011 of every one dollar of income produced, only 29 cents entered China’s markets. With net exports making a small annual contribution to domestic demand (even though they contribute greatly to the country’s capacity to invest and, thus, boost productivity), the onus falls increasingly on investment to meet the demand shortfall. However, as suggested in the avove paragraph, this emphasis on investment is a double edged sword, as it threatens to let the Giny out of the bottle in real estate markets, where bubbles have been looming threateningly for a while now.

| | 1990 | 1995 | 2000 | 2005 | 2009 | 2011 |

| Private Consumption | 49 | 44 | 45 | 40 | 34 | 29 |

| Investment | 35 | 42 | 36 | 42 | 48 | 58 |

| Government Consumption | 12 | 13 | 17 | 12 | 11 | 10 |

| Net Exports | 4 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 3 |

Composition of Chinese Aggregate Demand (Percentages of Gross Domestic Product). Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China

Woj’s Thoughts - Most economists agree that China needs to re-balance its economy away from investment and towards private consumption. China has made very little progress, if any, in this regard. As for the potential housing bubble, opinions are far more divergent. After a recent trip to China, my wonderful professor, Garrett Jones, remarked that families were using second homes as a savings vehicle but faced difficulty in abruptly moving their larger, extended families living under the same roof. While I respect that view, the growth of private debt to purchase homes leads me to side with Yanis.

2) When the Credit Transmission Mechanism Breaks… by Cullen Roche @ Pragmatic Capitalism

If you look at the 30 year mortgage rate closely you’ll notice a relatively steady inverse correlation between rates and new home sales. That is, all the way up until about 2007. Then, rates remain low and new home sales stay depressed. The low rate transmission mechanism breaks.

Why does it matter? This is exactly what we’d expect to see given the state of the balance sheet recession. You see, demand for credit is very low because households are still recovering from the implosion in their balance sheets. Instead of taking on more debt, households are paring back debt. This is clear from yesterday’s NY Fed report on household credit trends. And this is why monetary policy has been so broken in recent years. The Fed can’t gain traction because their primary transmission mechanism is busted. And the economy won’t feel quite right until this part of the monetary system starts working normally again….

3) Death of a Prediction Market by Rajiv Sethi

A couple of days ago Intrade announced that it was closing its doors to US residents in response to "legal and regulatory pressures." American traders are required to close out their positions by December 23rd, and withdraw all remaining funds by the 31st. Liquidity has dried up and spreads have widened considerably since the announcement. There have even been sharp price movements in some markets with no significant news, reflecting a skewed geographic distribution of beliefs regarding the likelihood of certain events.

…

It seems to me that the energies of regulators would be better directed elsewhere, at real and significant threats to financial stability, instead of being targeted at a small scale exchange which has become culturally significant and serves an educational purpose. The CFTC action just reinforces the perception that financial sector enforcement in the United States is a random, arbitrary process and that regulators keep on missing the wood for the trees.

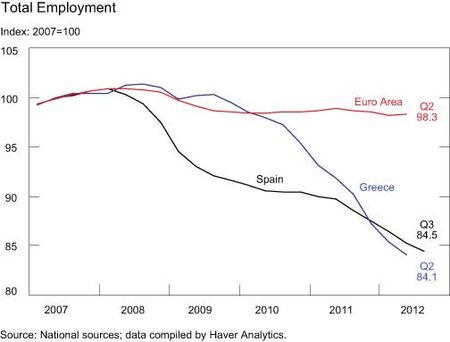

4) The Different Paths of Greece and Spain to High Unemployment by Thomas Klitgaard and Ayşegül Şahin @ Liberty Street Economics

The high unemployment rate in Greece is not surprising given the depths of its recession, but what explains Spain’s 25.8 percent unemployment rate given its much more modest downturn? One contributing factor is the fact that the composition of Spanish jobs made the economy vulnerable to dramatic job losses during a recession. In 2007, almost 13 percent of jobs in Spain were in construction, compared with roughly 8 percent in Greece and the euro area. Such a heavy weight on this sector made employment more vulnerable to a downturn given the fact that construction is the sector that typically experiences the steepest decline in a recession. Indeed, construction, as measured in the GDP accounts, fell 35 percent from 2007 to 2011, and the sector accounted for almost 60 percent of the decline in total employment over this period.

Another contributing factor is the very high percentage of employees tied to temporary work contracts in Spain. Data from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development show that 32 percent of employees in Spain worked under temporary contracts and 68 percent under permanent contracts in 2007. In Greece, 10 percent were on temporary contracts; the figure for Europe as a whole was 15 percent.

Woj’s Thoughts - Both countries suffer from excessive private debt that is being transferred to the public sector as the private sector attempts to deleverage. Considering the size of the housing bubble in Spain (the bust continues), the relatively large portion of jobs in construction before the crisis and decline in employment within that sector afterwards are no surprise. However, the percentage of temporary workers in Spain is striking (Does anyone know if this is tied to cultural or policy reasons?). As both countries attempt to move towards balance budgets, the downward trend in unemployment and GDP is likely to continue.

Greece has effectively defaulted again, for what I believe is now the fourth time in the past 3 years. Here are highlights from the full Eurogroup statement on Greece (h/t Delusional Economics).

The Eurogroup noted that the outlook for the sustainability of Greek government debt has worsened compared to March 2012 when the second programme was concluded, mainly on account of a deteriorated macro-economic situation and delays in programme implementation

...

Against this background and after having been reassured of the authorities' resolve to carry the fiscal and structural reform momentum forward and with a positive outcome of the possible debt buy-back operation, the euro area Member States would be prepared to consider the following initiatives:

• A lowering by 100 bps of the interest rate charged to Greece on the loans provided in the context of the Greek Loan Facility. Member States under a full financial assistance programme are not required to participate in the lowering of the GLF interest rates for the period in which they receive themselves financial assistance.

• A lowering by 10 bps of the guarantee fee costs paid by Greece on the EFSF loans.

• An extension of the maturities of the bilateral and EFSF loans by 15 years and a deferral of interest payments of Greece on EFSF loans by 10 years. These measures will not affect the creditworthiness of EFSF, which is fully backed by the guarantees from Member States.

• A commitment by Member States to pass on to Greece's segregated account, an amount equivalent to the income on the SMP portfolio accruing to their national central bank as from budget year 2013. Member States under a full financial assistance programme are not required to participate in this scheme for the period in which they receive themselves financial assistance.The Eurogroup stresses, however, that the above-mentioned benefits of initiatives by euro area Member States would accrue to Greece in a phased manner and conditional upon a strong implementation by the country of the agreed reform measures in the programme period as well as in the post-programme surveillance period.

While I fully expect the market and economic blogosphere to cheer this new agreement, I remain convinced that this deal will be as equally unsuccessful as the previous three (not including the many failed agreements for other countries). From my perspective it is not surprising that Greece’s economic situation has worsened during the past year. What is surprising is the Eurogroup’s ability to commend Greece’s efforts and push to strengthen those previous efforts that have resulted in an increasingly unsustainable economic and political environment.

This agreement, once again, does not actually reduce sovereign debt outstanding but, instead, reduces the interest rate and extends the maturity of previous loans. Although this eases the debt burden ever so slightly, the conditionality of further structural adjustment practically ensures the economy will continue to dramatically underperform. This declining growth will continue to offset attempts to reduce the budget deficit or debt-to-GDP ratio. Considering the lofty expectations for Greece’s economy and budget that accompany this agreement, I feel confident in predicting that a future agreement will read:

The Eurogroup noted that the outlook for the sustainability of Greek government debt has worsened compared to November 2012 when the fourth programme was enacted, mainly on account of a deteriorated macro-economic situation.

Europe is clearly determined to continue kicking the can down the road. Despite the continued optimism regarding each new agreement, the economic reality is that unemployment keeps rising and growth remains in decline, especially for peripheral Europe. The parade of ineffective agreements is far from over.

Related posts:

ECB's Changing Philosophy is Good for Bond Holders but Bad for the Economy

ECB's Means (Lost Decade With High Unemployment) To An End (Structural Reform)

Europe's Leaders Should Learn From Game of Thrones

Unending Subordination of Private Creditors Continues

I was reading an article from one of the banks that was talking about how low Greece’s CAPE was (the article cited around 2). I wanted to examine what happens when a CAPE was really, really low. So, we looked at the database for all instances where CAPEs were below 5 at the end of the year. We only found nine total out of about 1000 total market years.

US in 1920

UK in 1974

Netherlands 1981

South Korea 1984,1985,1997

Thailand 2000

Ireland 2008

and…Greece in 2011

Can you imagine investing in any of these markets in those years? Me neither. In every instance the newsflow was horrendous and many of these countries were in total crisis.

Now what would happen if you invested in these markets, the literal worst of the most disgusting terrible markets/economies/political situations? Below are local country real returns (net of inflation):

On average:

1 Year: 35%

3 Year CAGR: 30%

5 Year CAGR: 20%

10 Year CAGR: 12%

Read it at World Beta

Blood in the Streets, or Greece

By Mebane Faber

Looking at the headlines makes one extremely hesitant about investing in Greece or the other European periphery nations. However, this data provides a tempting reason to take a contrarian point of view. Current economic deterioration is proving politically unstable, which makes drastic actions increasingly likely in the next few years. At such low levels of investor sentiment, the chances that actions/outcomes surprise to the upside are ever more favorable.

(Note: I’m currently long EWP, the iShares MSCI Spain Index Fund)

Related posts:

Niels Jensen - "a eurozone exit is not the Armageddon"

Is Non-Existent Austerity Priced in to Euro Stoxx?

Bring Back the Deutsche Mark!!

My stop loss over the next 4-6 weeks while I expect this risk-on phase to play out is simple: a weekly S&P close below 1267 would for me be very bearish and likely change things. But as mentioned, instead I expect to see markets struggle with headlines and volatility, but ultimately climb the wall of worry up towards 1400, perhaps 1450 S&P.

And then? Well, again things are largely unchanged from my April note. Much beyond late July or early August, and assuming we get to 1400/1450 S&P, I then would look to position for an extremely bearish risk-off phase over late August through to November or December. The drivers of this extremely bearish expected phase are not new: overly bullish positioning and sentiment; weak global growth, not just in the eurozone but also in the US and the BRICs; the next leg of crisis in the ongoing eurozone debacle in my view; and of course the looming US fiscal crisis, which in my view is not even "slightly" priced into markets, but where I feel the probability of a crisis is close to 75%. Hopefully by year-end US sell-siders will realise that blaming the eurozone crisis for everything that is going wrong in the US has been a serious error, which has resulted in them being blind-sided to the other real „gorilla?s in the room? – namely the US debt/fiscal weakness, and the hard landings now beginning in the BRICs.

My forecast for this extremely bearish risk-off phase over late Q3 and Q4 is that the S&P500 trades below the low of last year, perhaps as low as 1000 +/- 20. The iTraxx Crossover index should over that period widen from around 550/600bp (my end July/early August risk-on target) out all the way to certainly 800bp, and more likely closer to 1000bp. And we should see core bond yields rally hard – I expect 10yr UST yields to rally from my 2.35%/2.45% end July or early August target, all the way down to 1.5%, maybe even lower.

Read it at Zero Hedge

Bob The Bear Is Briefly Bullish... Before Things Go Boom

By Bob Janjuah

Volatility is picking up as the markets swing back and forth on each new data point or rumor. Bad economic news is once again good for markets, which are salivating over the potential for more monetary stimulus from the Fed next week. With expectations for further easing moving higher by the day, the chances that Bernanke May Disappoint Pavlov's Dogs continues to grow. Most market participants also expect the Greek elections this weekend to be won by pro-bailout party New Democracy, who would then form a coalition with Pasok. Syzria, however, should not be counted out and would likely be a negative surprise to markets.

The potential for either of these unexpected outcomes, in my view, is far higher than markets are currently discounting. If I’m wrong, markets may very well follow the trend laid out by Janjuah (since neither outcome resolves the actual problems). If I’m right, the markets may be in for a nasty surprise shorter-term.

The ECB is not openly discussing this, but these ELA euros are coming from TARGET2, further raising GoB's liability to the rest of the Eurosystem. Furthermore the collateral requirements for ELA are far less stringent than the ECB's standard financing facilities such as MRO and LTRO. In case of a possible re-denomination, the ability to recover ELA collateral with any material value will be quite minimal.

Read it at Sober Look

Greek ELA growth poses increasing risks for the Eurosystem

By Walter Kurtz

The risks and size of potential ECB losses continues to grow as time passes and Greece remains part of the EMU (part of the Greek strategy?). Although the ECB cannot run out of Euros (go bankrupt), incurring actual losses blurs the line between monetary and fiscal policy. This result, which seems increasingly probable, will likely hinder support for further expansions of the ECB’s balance sheet.

...is from p.98 of Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff’s outstanding book, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (2011)

“Greece, as noted, has spent more than half the years since 1800 in default.”

Over the past three years, countless officials from the EU, ECB and IMF have proclaimed that no country within the Eurozone would be allowed to default. Given the history of many European countries, especially Greece, trying to prevent default seemed absurd yet authorities initially appeared willing to provide endless sums through bailouts to avoid a single default. Although Greece has been loaned funds in excess of the initial amount of debt outstanding, the countries economic deterioration and continually lax collection of taxes proved to much for the authorities. As of Friday, Greece has once again defaulted on its sovereign debt.Although Greece’s default will create losses for the private sector of around 100 billion euros, Greece’s debt outstanding still remains more than 160% of GDP. With the economic contraction picking up speed (last quarter GDP was down 7.5% on an annual basis), any hopes of that percentage decreasing in the near future are ridiculously optimistic, if not impossible. By practically any standard, Greece is currently living through a Depression that appears to have no end in sight. The majority of Greece’s outstanding debt will now be held by the EU, ECB and IMF. These holdings are senior to all other claims, making future defaults more difficult and complicated. Regardless of these hurdles, Greece can not and will not repay the current debt outstanding. Another default/restructuring is a practical certainty and will likely occur in the next couple years. Hopefully by that time the Greek people will have an elected leader that places the interests of the people first and finally takes Greece off the Euro. European authorities tried to ensure this time was different by preventing sovereign defaults from ever occurring again. History was not on their side and ultimately won out, as it has for many centuries. In the end, this time was not different and Greece will likely spend more than half of the next decade in default as well.