During the past few years many individuals, including myself, have been surprised by how strong the rebound in corporate profits has been amidst a weak recovery in GDP and unemployment. New all-time highs in corporate profits have seemingly been the main driver behind the more than 100% rise in the S&P 500 since its lows in March 2009.

Richard Bernstein supports this view in The First Sign of Weakness in Corporate America:

“Our research over the past twenty-five years has consistently suggested that profit cycles, rather than economic cycles, drive equity markets.”

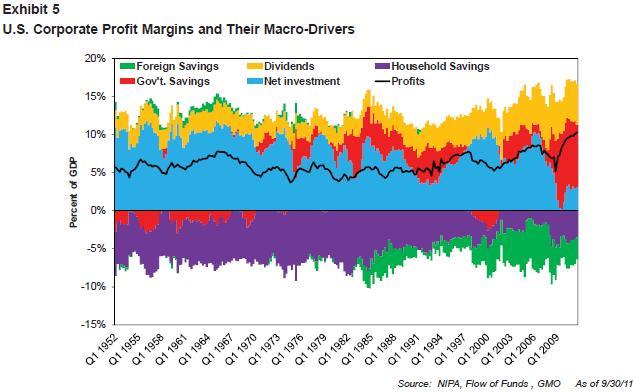

Bernstein’s research note comments on the recent rise in companies reporting negative earnings surprises and negative earnings growth (year/year). Although corporate balance sheets are much improved over a few years ago, these factors are warning signs that profit growth is slowing and may turn negative. Another highly regarded investor/analyst, James Montier of GMO, is also now expressing concern over a profit recession in his recent commentary What Goes Up Must Come Down. Montier is part of a relatively small group of individuals/investors that foresaw the large rise in corporate profits based on its relationship with government deficits. A common trait among this cohort is a view of economics consistent with Post-Keynesian macro, including its different branches e.g. MMT and MMR.Montier breaks down the components of corporate profit margins in a flow of funds framework:

Profits = Investment – Household Savings – Government Savings – Foreign Savings + Dividends

This arrangement is an expanded derivation of (Michal) Kalecki’s profit equation, which says

Retained Earnings = Investment + Government Deficit - Household

Savings

The insightful blogger, Ramanan, recently provided a more detailed background of Kalecki’s Profit Equation. Looking at corporate profits in this manner displays that government deficits have been the primary driver during this recovery.

For the current fiscal year (2012), the budget deficit (Gov’t Savings) is still expected to be more than 8% of GDP (over $1 trillion). However, with tons of tax breaks potentially expiring at the end of this year, next year’s budget deficit could be significantly lower (~5% of GDP). If this occurs then corporate profits are likely to decline in 2013. Regarding the murkiness of next year’s budget outlook, Cullen Roche also chimed in on WHERE ARE CORPORATE PROFITS HEADED? He comments, and I agree, that regardless of upcoming elections the budget deficit next year may very well end up being higher than current CBO projections. The following chart depicts possible outcomes for profits based on his assumptions:

For the current fiscal year (2012), the budget deficit (Gov’t Savings) is still expected to be more than 8% of GDP (over $1 trillion). However, with tons of tax breaks potentially expiring at the end of this year, next year’s budget deficit could be significantly lower (~5% of GDP). If this occurs then corporate profits are likely to decline in 2013. Regarding the murkiness of next year’s budget outlook, Cullen Roche also chimed in on WHERE ARE CORPORATE PROFITS HEADED? He comments, and I agree, that regardless of upcoming elections the budget deficit next year may very well end up being higher than current CBO projections. The following chart depicts possible outcomes for profits based on his assumptions:

Looking ahead I doubt much, if any, of the decisions on future tax rates get decided before the November elections. If recent debates in Congress offer any insight, decisions on the budget will remain on hold until the last possible minute. Fearing the potential outcome in red above, investors may seek safety in advance...

Looking ahead I doubt much, if any, of the decisions on future tax rates get decided before the November elections. If recent debates in Congress offer any insight, decisions on the budget will remain on hold until the last possible minute. Fearing the potential outcome in red above, investors may seek safety in advance...